Considered one of the greatest portrait photographers in history, Judith Joy Ross’s images are built on radical degrees of vulnerability and trust on both sides of the lens

Few in the history of portrait photography have exhibited such profound faith in the ordinary individual as Judith Joy Ross. Nearly all the photographs the revered American photographer has been making since the 1980s have memorialised her epiphanic encounters with strangers she’s just met. “Both of us together, we make the picture,” Ross has said of her shooting process, with which she uses a bulky, old-fashioned 8x10 view camera. “You don’t have any responsibility like raising children or putting kids through college. It’s just instant gratification … We both might actually be in love for a few seconds. I’ll never see them again.”

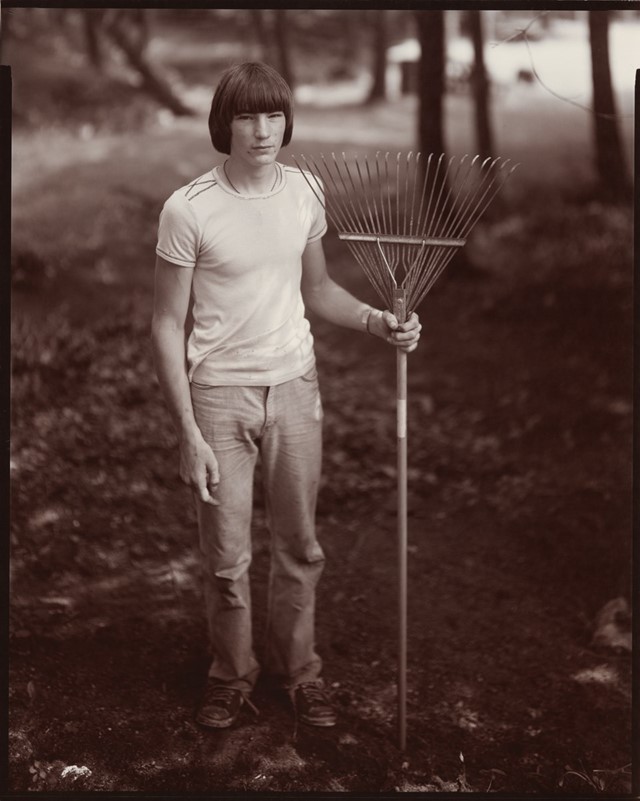

Although Ross does not seek people out for their oddity à la Diane Arbus, she is devoted to the minute annotation of quirks. This is best displayed in her first great portraits: those taken in 1982 of young bathers in Eurana Park, Pennsylvania, where Ross spent her childhood summers. They were informed by the question: “Why is life worth living?”, made heavier by the recent passing of her father. “I couldn’t look at adults,” she said. “They all had pain in their faces. The children didn’t.” What they did have, however, were the solemn expressions of people whose knowledge of the world and themselves was still being formed. The pictures – the boy with a bowl haircut who stiffly holds a rake or the girls who awkwardly conceal their bathing suits – speak to the burdens such knowledge brings.

As made evident by Judith Joy Ross: Photographs 1978–2015, a miraculous retrospective book edited by Joshua Chuang and co-published by the Fundación MAPFRE and Aperture, children were amongst Ross’s first photographic subjects, and have become her most enduring ones too. Offering readers a revelatory number of previously unpublished plates, the catalogue is organised chronologically into Ross’s “campaigns” – as art historian Svetlana Alpers calls them – such as mourners at the Vietnam Veterans Memorial, US army reserves on red alert or pupils in Hazleton schools. While Ross’s subject matter has, over the years, branched out to encompass public institutions and national politics, she has always been guided by a genuine curiosity – and trembling respect – for the individual. This is never expressed as “rose-tinted flattery,” Chuang explains, “but as a mirror bearing an essential, fleeting truth – one able to transcend the specifics of who, when, where and why.”

So startling in their emotional acuity, Ross’s portraits beg the question: has she drawn out her subjects’ personhood or have they revealed themselves? Chuang believes both dynamics are at play: “Ross has said her wooden box camera works as a charm, but so does she, given the disarming attention she pays to the people before her.” It’s the quality of mutual recognition – the recognition paid by the photographer, the recognition paid by the subject to the act of being photographed – that creates the moral theatre of Ross’s intense, contemplative portraits. The photographer Robert Frank once said that each photograph should contain “the humanity of the moment”. Each of Ross’s photographs contains this in spades.

Vince Aletti calls Ross a “model of restraint”. Indeed, her gaze is infinitely sober, even when, for example, singling out the impassioned faces of those who took to Pennsylvania’s streets in protest of the Iraq War. “My intention was to use the portraits as propaganda,” Ross has said. “To [show] the American public that a protestor is this and not some kind of raging fool, maniac, enemy, other.” Having confronted what she called her “cowardice in taking yet again one more stand,” Ross compiled her portraits in a pamphlet-sized book with the words ‘protest the war’ emblazoned on its red card cover. She went to Capitol Hill with cartons of copies and distributed them by hand to congressional offices. “However naive,” Chuang notes, “Ross’s conviction that ‘if we could really see who we are, the world would change’ was what sustained her project. The photographs were rejected for publication by The New York Times but, for me, the work’s effect as a testament of individual agency endures.”

In her civic inquiries, Ross owes a huge debt to German photographer August Sander. Yet, where he classified his fellow citizens according to social status and profession, Ross stresses the individuality of her subjects when stripped of their acquired roles and societal guises. Ross therefore may be, in spirit, closer to Walker Evans, who too aspired for transparency and transcendence. By way of Ross’s arcane process of gold-toning – through which she yields varying shades of plum browns and soft, purplish greys – she elevates the emotional resonance of each print: an epiphany made manifest. “Photographs are much more appealing to me than life,” Ross said. “Life is too hard, too complicated, too meaningless, too everything … If you look at a photograph, you think you understand something.”

For photographers, Ross’s tender, intricately crafted studies are about as good as it gets. She happened to be born in small-town eastern Pennsylvania, where she has made almost all of her work, but one feels that she could have recorded any number of peoples. If only she could have carried her camera, bellows and all, back to the courts of Caligula or Louis XIV. In our current era, when the idea of photographing someone’s essence is suspect, Ross feels like a precious anomaly. We might not deserve the immense sincerity, but her greatest gift is in showing the humanity – the “human-kindness” – we all share.

Judith Joy Ross: Photographs 1978–2015 is co-published by the Fundación MAPFRE and Aperture. An accompanying exhibition runs at LE BAL, Paris until 18 September 2022.