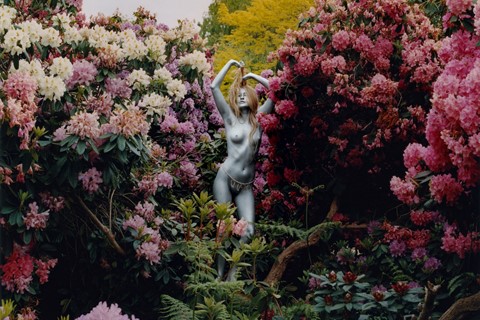

Steph Wilson began taking experimental photos of herself naked during the first quarantine in 2020, and hasn’t stopped since. Her “rather flamboyant” ongoing series, titled Self (WIP), sees the London-based image-maker transform into a cacophony of characters; in some cases exploring versions of herself; in others, imagined personalities. The series takes us through a wide spectrum of themes and moods – ranging from ethereal and goddess-like portraits, to surreal, silly and even self-abasing imagery. In one portrait we see Wilson pose regally in a recreation of the 1585 painting A Young Daughter of the Picts by Jacques Le Moyne de Morgues, while elsewhere we encounter her folded in half, legs overhead, with a lit candle sticking out of her bum.

For Wilson, what began as a fun project turned into a deeper exploration of self. It became a study of our disjointed relationships with our bodies, what it means to portray your naked body as a female artist, and the beauty to be found in the “unimpressive” and “everyday” reality of our physical selves. Vitally, the project was also a way of questioning the limiting erotic, delicate or ‘perfect’ depictions of the female nude – tropes which have been established by male artists throughout history. “By only promoting images of women projecting beauty, perfection and power, it seems disingenuous,” she says. “I want to see women who don’t give a shit about looking shit.” So, in the making of her series, Wilson allowed herself to be “humorous or ridiculous”; “ugly” and “sluttish”, and in the process developed a deeper creative trust in herself.

Here, in an email exchange with AnOther, Wilson speaks on pushing her personal limits through the nude and the joy to be gleaned from making yourself “as unattractive to men as possible”:

Orla Brennan: Can you tell us when you started taking nude self-portraits?

Steph Wilson: I can’t remember a time that I wasn’t shamelessly looking for an excuse to get naked. I think my first actual intentionally artistic nude was at school, which undoubtedly tested the professionalism of my tutors. What do you do when an obnoxious 15-year-old girl who breeds ferrets presents photos of her naked body adorned in post-it notes of misquoted Oscar Wilde? I’ve never really considered what I enjoy about it. There’s a sense of ‘breaking the rules‘ by being so unphased about being naked.

OB: Much of the project was taken during lockdown – a time many artists have said brought new intentions into focus for them. Did that period of time change your approach to your practice?

SW: Rather than change my approach, it more instilled what I already found so important: creative freedom and space to explore something organically. It was pretty blissful spending a day in the studio during those early, unexpectedly hot summer mornings just seeing where an idea would go. It felt very akin to painting, something I did previous to photography. Much more lonesome, but in a lovely way.

OB: Who did you work with on the series?

SW: My partner, Tom, was a very enduring assistant. Harrison Ball (The New York City Ballet), Dilara Findikoglu, Mona Leanne, Ali Pirzadeh, Laura Little, Yushi Li, James Shaw.

“I find our broken relationships with our bodies quite touching. We give them such a hard time, consider them as other to ourselves, as works of improvement. It’s like our heads are very separate from them” – Steph Wilson

OB: How do you feel when posing nude?

SW: I photographed a friend nude in Mexico recently and she told me that, had she been clothed, she would have felt vulnerable and stiff. It was because she was entirely naked she felt she could relax in front of the camera: she no longer had anything to hide. I think that encapsulates how I feel; that once naked you have entirely given in to yourself.

You’re a body: unfixed and soft and everyday. There’s a beauty in how unimpressive our bodies are. Bodies are often compared to finely tuned machines or showcased as powerful or resilient. They’ve been dressed up as symbols of potential, conduits for political agendas, targets for shame, when ultimately, they’re a type of home. I enjoy living in mine.

OB: You’ve mentioned that the series pushes your personal boundaries, playing with ideas of self-abasement. Can you tell us about this?

SW: I find our broken relationships with our bodies quite touching. We give them such a hard time, consider them as other to ourselves, as works of improvement. It’s like our heads are very separate from them; perhaps that’s why I’ve experimented in using my own in this series as a sort of prop. I think I trust my relationship with my body enough to ridicule it in some way, to make it ugly or sluttish. The idea of playing with self-abasement came later in the series after initially enjoying making something more escapist. I realised I hadn’t negotiated any boundaries with myself, so I wanted to see where they lay.

Women’s bodies are often portrayed so seriously, delicately or erotically. I started wondering why women didn’t seem to be allowed to portray themselves (and their bodies) as humorous, ugly or ridiculous. Is it a fear of being devalued? By not making a mockery of this “value system” designed by men, are we not just sustaining it? By only promoting images of women projecting beauty, perfection and power, it seems disingenuous. I want to see women who don’t give a shit about looking shit; so when I look shit, I don’t give a shit.

OB: What was your creative process like in planning these scenes?

SW: There truly wasn’t much of a process beyond what I felt like doing that week – be it more whimsical and utopian during lockdown, or a rawer and more spontaneous moment in a wagon at a friend’s wedding. I didn’t want the series to ever feel like a chore, so allowed for it to shape itself over time. It’s why I stopped doing them as frequently at the start of 2022. I got busier with work and I began feeling a nagging pressure to continue, which defeated the original point. I may do three next month, or a single one this year. All I know is the final published works will span very many years.

OB: Which portrait do you feel most closely represents your true self?

SW: Probably the shot of me sunburnt surrounded by dick pics and Pomeranians.

OB: Are there any self-portrait series by other artists which have inspired you?

SW: I’ve always been a massive fan of Ana Mendieta. Tracey Emin’s self-portraits were some of the first I’d seen by a woman that didn’t concern looking “pretty”, and I often think about Hannah Wilke’s images of herself with tiny chewing gum vulvas placed on her face and body. Women use their own bodies so often in art, don’t they? It’s like an inherited trauma. We feel such a need to reclaim what it is that has been taken away from us time and time again. It’s actually made me quite sad, thinking about it.

OB: Did you learn anything new about yourself in the process of making this series?

SW: I really enjoy making myself as unattractive to men as possible.

OB: You’ve mentioned that the project will be ongoing. What are you excited to explore next?

SW: I’m letting this hiatus from the series take as long as it needs to. There seems to be a huge rush in photography these days to constantly get published, and you see a thinning of the work’s impact as a result. I’ve got another project on the go, so I’m giving that my sole attention for now. Nevertheless, if a situation presented itself to me, I’d still jump at it. I love the idea of carrying on until a very old age – each portrait reflecting my milestones, obsessions, desires, inspirations or politics at every life interval. For instance, if I got pregnant I’d love to play with that; rolling around like a ball in a pigsty or something.

Follow Steph Wilson on Instagram for future instalments of this and future projects.