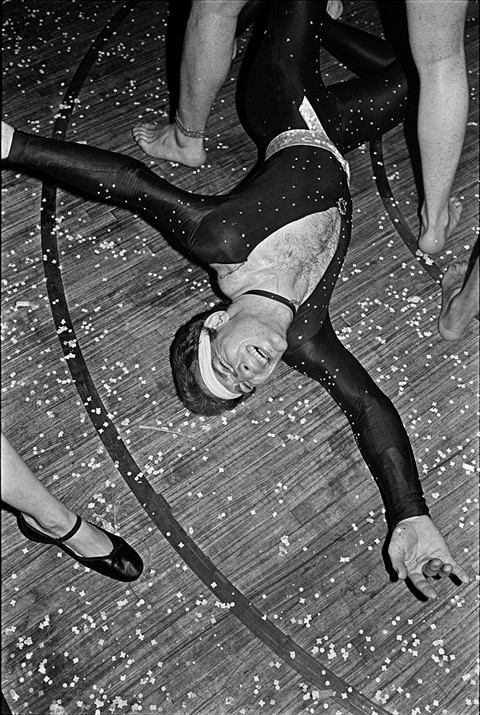

“Even though it was a very hedonistic and wild time with all this sexuality and sensuality to it, I still see it as a very innocent time,” says Bernstein, whose photographs from the era are currently on display in London

Though disco was reductively dismissed as a fad during its 1970s heyday, it continues to intrigue and inspire more than 40 years later. It’s surely no coincidence that when club culture was hobbled by the pandemic in 2020, a ripple of brilliant pop albums celebrated its glittery aesthetic and dance floor drama: Dua Lipa’s Future Nostalgia, Jessie Ware’s What’s Your Pleasure?, Kylie Minogue’s aptly titled Disco. When we couldn’t go ‘out out’, we looked back to one of nightlife’s most iconic moments.

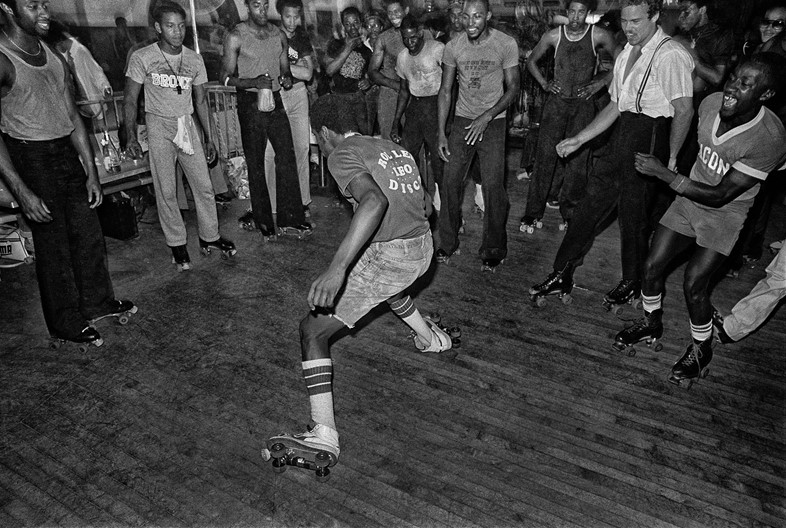

Now comes Glitterbox Presents Last Dance, a new exhibition of Bill Bernstein’s evocative and vibrant photographs documenting New York City’s legendary disco scene. Presented by the disco-influenced club collective Glitterbox in the basement of their east London headquarters, it offers a heady trip back to the sweaty dance floors of Studio 54, G.G.’s Barnum Room and Better Days. The exhibition even features a floor-to-ceiling print designed to conjure up Paradise Garage, the hallowed SoHo club that attracted a predominantly Black LGBTQ+ crowd. “Paradise Garage was a real dance space with almost a cult-like following,” Bernstein recalls, speaking on the phone from his Manhattan apartment. “Larry Levan was a DJ there and even back then he was really well known for being the most amazing DJ.”

Bernstein says that when The Village Voice first sent him to photograph an event at Studio 54 in December 1977, he was thrilled – partly because he had been turned away a few weeks earlier by the notoriously selective door staff. “I was genuinely curious about Studio 54 and wasn’t quite sure what to expect,” he recalls. “It had a reputation for being a very hedonistic place and a real celebrity hang-out.” Bernstein isn’t exaggerating: everyone from Grace Jones and David Bowie to Divine and Liza Minnelli partied there. When Bianca Jagger celebrated her birthday at Studio 54 in May 1977, co-owner Steve Rubell arranged for her to be greeted on the dance floor by an actual horse. Studio 54 was literally a converted theatre, but it also cultivated a reputation as a theatre of dreams.

The function Bernstein was sent to cover was a relatively staid affair honouring Lillian Carter, the humanitarian mother of then-President Jimmy Carter. Still, because this was New York in the late 1970s, Mrs Carter was seated at dinner next to Andy Warhol. Cunningly, Bernstein hid on the balcony after her party finished so he could carry on snapping once the usual Studio 54 crowd poured in. He wasn’t disappointed. “I was very taken by the look of the crowd, the feel of the crowd, everything about it,” Bernstein recalls, still sounding pretty rapt 45 years later. “You had the wealthy New Yorkers from the Upper East Side and the Wall Street crowd – you know, people in nice suits – but also downtown artists and the gay and transgender crowd. It was really a very, very diverse mix of people who seemed to seamlessly mix on the dance floor. And to me, that was really quite something to see.”

Entranced, Bernstein spent the next couple of years documenting the disco scene whenever he could between paid assignments. Whereas other photographers focused on Studio 54 and its admittedly dazzling glitterati, he took a broader and more intuitive approach, shuttling between numerous uptown and downtown clubs and reading the room. “When I got to a club, I would actually spent a lot of time not taking a picture,” he says “I would be looking around and really taking in the kind of people that were there. And then, I would try to photograph the people who interested me the most and who represented the feel of the club and what was going on in New York City at that time.”

Bernstein believes Manhattan nightlife was able to shine so brightly in the late 1970s because the city was still accessible to everyone. “Rent was really cheap – I lived in SoHo at the time and I paid $125 a month for my space – and that attracted a lot of very interesting artistic people,” he says. “But at the same time, you can’t overstate the influence of queer culture on disco in terms of fashion, music, the way people danced, all that kind of stuff.” In a cruel but perhaps all too predictable twist of fate, this sense of gay abandon led to the so-called ’disco sucks’ movement, a petty but increasingly pernicious protest from white rock fans who were threatened by the pre-eminence of a genre rooted in Black and queer communities. Disco was also a victim of its own success: by crossing over into the mainstream, it lost its subversive glamour and essentially fizzled out at the turn of the decade.

Interestingly, Bernstein says that when he looks at his disco photography with modern eyes, he is struck by a fundamental paradox. “There’s a kind of innocence to it, in a way, in terms of the openness and freedom of expression,” he says. “Honestly, even though it was a very hedonistic and wild time with all this sexuality and sensuality to it, I still see it as a very innocent time.” It’s precisely this paradox that continues to fascinate us today.

Glitterbox Presents Last Dance is at Defected Records Basement until April 29.