As his new exhibition opens at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York, the artist tells the story behind his photographs of Andy Warhol, Jean-Michel Basquiat and Pat Cleveland

The quote “making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art” has marked Andy Warhol out as the most well-known commodity fetishist of the 20th century. Money, a new exhibition of Christopher Makos’s photography at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York, displays a body of work which captures Warhol’s preoccupation with financial success – but also with celebrity, and the notion of persona.

Inspired by Man Ray muse and Duchamp’s alter ego Rrose Selavy, the show contains portraits of Warhol in drag, which are indicative of the pair’s captivation with modes of self-construction. But the show also includes self-portraits and collages by Makos, where we see the photographer exploring his own capacities as the impresario of both his own image and outer life, in a way that eerily foreshadows future generations’ obsessive pull towards the careful self-curation of life on social media.

Makos and Warhol met in 1975, a key point of transition from the ‘good’ Warhol of the 1960s and the ‘bad’ (corrupt) Warhol of the 1970s and 1980s; a period when the artist was roundly critiqued as a crass, commercial figure for charging thousands of dollars for celebrity commissions.

Money prompts us to reassess late Warhol by inviting us into his world: to see the things he saw, the things he did, and the people who surrounded him. Warhol had an alchemical capacity to transmute aspects of his psychic life and the observed features of American society at large into art; Makos was also fascinated by the means by which one can assemble parts of identity – and his images allow us to reassemble our own ideas of Warhol as a complicated and often conflicted man.

Here, in his own words, Makos tells the story behind five images from the exhibition.

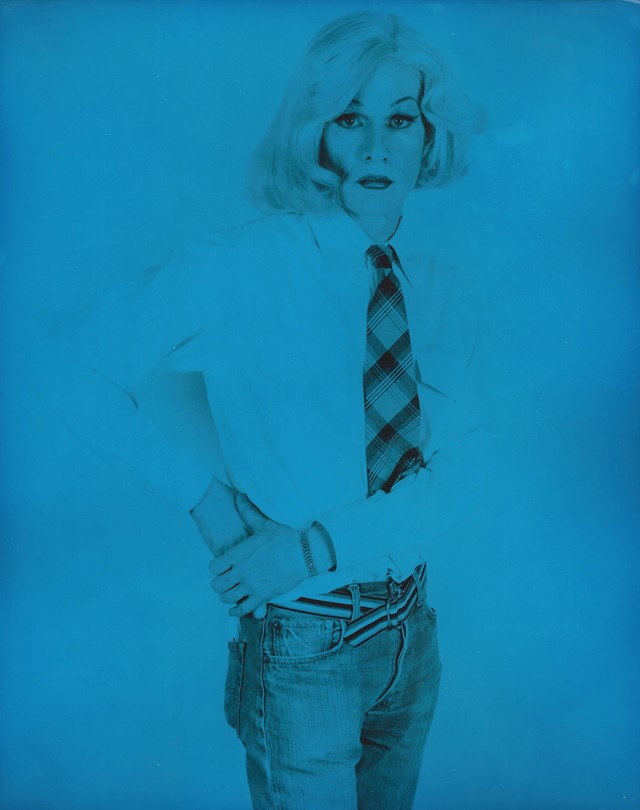

Andy with Wig, 1981

“This image is from the second shooting of The Altered Image series. We had a theatrical makeup person come in and paint his face absolutely white. With spirit gum, we taped down the eyebrows and created a canvas. Here we see the hair people working with Andy, depicting the moment just before the wig’s removal, so it’s referencing the wig snatch [of 1985, when a young woman realised Warhol’s worst fears by stealing the wig off his head at a book signing]. Look at him – Andy was always on with me. Even when he was being prepped. You can see the intensity in his eyes. He was always the model, working every picture.

“People ask, when they see this series, whether Andy wanted to be a girl. Absolutely not. Andy just wanted to be pretty. Everybody wants to be pretty. And I wanted that for him. He was my muse and my whole world at the time.

“The project was inspired by Rrose Selavy – Duchamp’s feminine alter ego and the muse to Man Ray, whom I apprenticed with in Paris. But unlike Duchamp, we kept Andy in his normal clothes and only worked on his face. Halston asked us if we wanted to borrow a dress. In retrospect, I should have said yes. But we were playing with just the idea of altering his image. You see, in all these images there’s no female dress but a tie, and in some of them, his own hair – I always refer to him as having his own hair unless he is wearing a woman’s wig. So there’s a push-pull going on. A fracturing of his identity created by the fact he’s dressed as he would normally be from the neck down.”

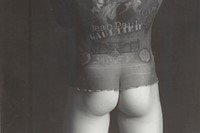

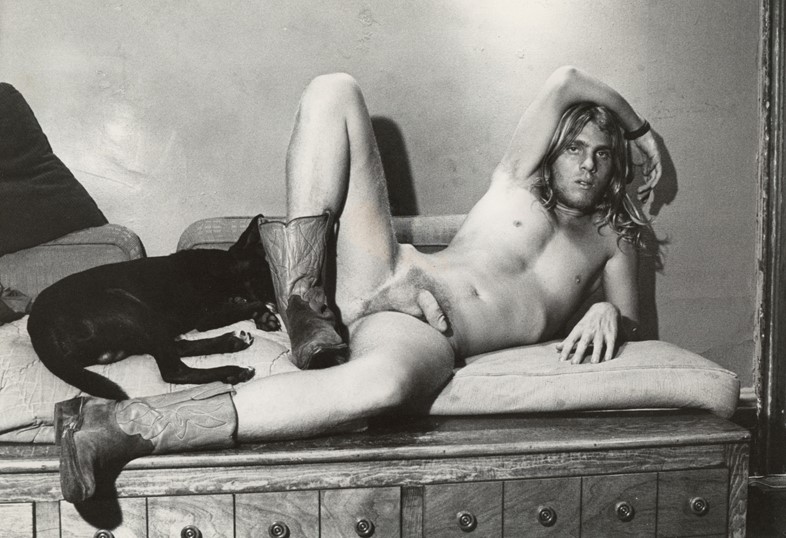

Self Portrait with Dog, 1970s

“Well look at me, ha! I’m just a youth in New York doing my Instagram pose. I see how the photograph was riffing on the kitschy gay pornography [that started being produced in the late 1950s in New York] but only in a surface way. I always thought it’s much more fun to be the porn yourself. But let’s be clear, I wasn’t a porn star and I wasn’t a hustler.

“I wasn’t really into the narrative about my sexuality on the show. Everyone in the 70s and 80s was trying to get out of boxes. In today’s world, so many people want you to define who you are. Which really, I think, is alienating. In this image – I don’t know if it was my Italian-Greek background, being a Capricorn, being stubborn – you can see a young man who is very aware of himself. When I came to New York in the early 70s, I was fully committed to being me. I had made the decision that this was what I wanted to do and who I wanted to be. And I committed to that.”

Halston and Pat Cleveland At Andy’s Summer House, Montauk, 1981

“These were taken in the Stanford White group of houses – Eothen, in Montauk – that Andy owned and Halston rented, the Rolling Stones rented … There’s so much history in them, not only architecturally, but because of the people coming through them.

“They are important photographs to me because they are about joy and happiness. They were taken during a period that everyone defines by the Aids epidemic, but what we see in these images, and what it’s important to remember, is that while that was going on there were other levels of happiness that we worked really hard to create.”

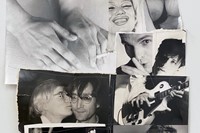

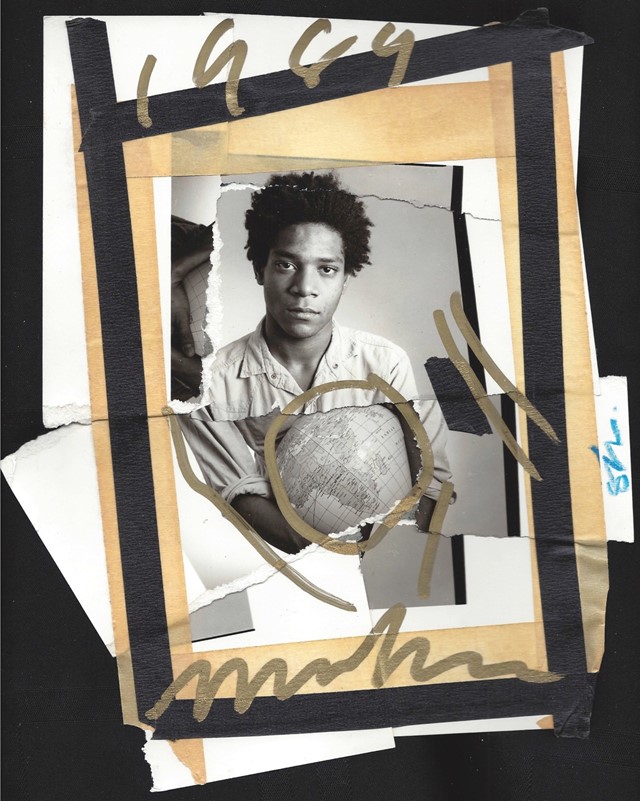

Basquiat Collage 3, 1989

“I made this collage out of strips of negatives and leftover prints I had lying around the studio. I was so in awe of him [Basquiat], I just thought he was the most unbelievable artist, breaking all the rules. Everybody who was an emerging artist at that time was a white boy and here comes this super cool guy. In the original photo, he was holding up Africa. I went to his studio to do some portraits and Basquiat held up the blow-up globe. He just really didn’t want to be the one token Black artist in the group.

“And The New York Times review of Warhol and Basquiat’s [1985 collaborative] show, which described Basquiat as Warhol’s ‘mascot’ – that’s exactly what he didn’t want. He was already so fragile. When I would go to his studio during that time, he was already taking heroin, and when you went in, so many of the paintings that you see now selling for hundreds of millions of dollars were just on the floor with his sneaker prints on the corners of them. And there would be his pans, like he’d have had eggs or something, all leftover in a corner next to just these wads and wads of cash stacked up all over the place. He was making money hand over fist at that point, and there was nobody helping him navigate it.”

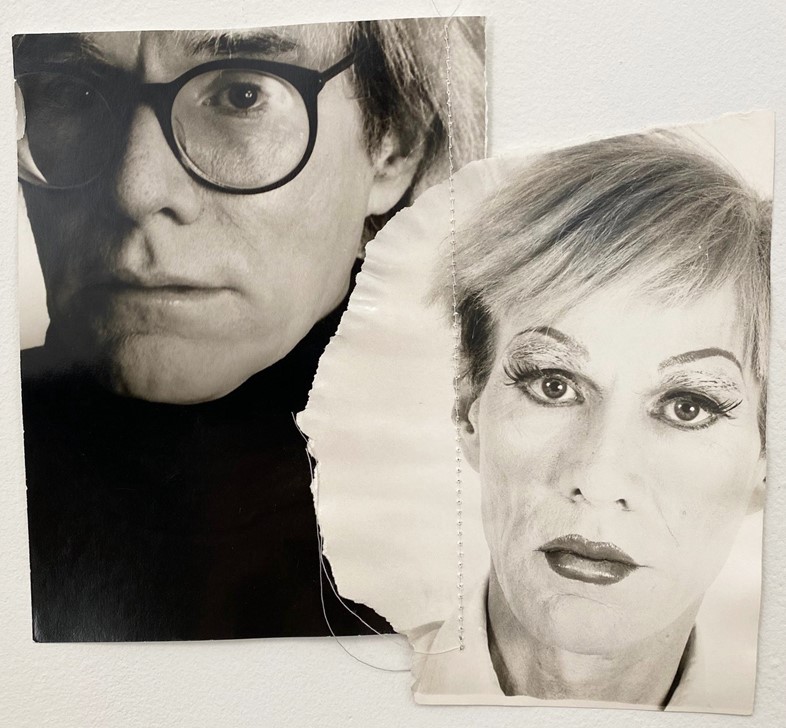

The Two Sides Of Andy, 1981

“This collage is called The Two Sides of Andy, where we see Warhol in a turtleneck and thick black frames sewn together with a photograph of Andy in drag from the Altered Image series. With the thick winged eyeliner and his regular hair, he sort of looks like Edie Sedgwick. She died before I knew Andy and was part of the first Factory. I was part of Factory two and three. But there’s the femme fatale thing going on.

“Was he envious of women and female beauty? Well, Andy didn’t want to be a girl. What Andy was interested in was drag queens as manipulators of self-image, like all the women in his paintings, Jackie [Kennedy] and Marilyn [Monroe], they had their public images and then behind them, a different reality.

“The idea that there was another side to Andy was part of The Andy Warhol Diaries [Netflix] series. Watching the show really made me wish I’d hugged him more and told him how fabulous he was. I knew he had issues with his appearance, but not to that extent. They did a great job, but I would say he was a happier person than the show portrayed.

“Do you know what’s funny and what wasn’t really discussed in the show? The diaries actually started out because Andy needed to track his expenses for tax reasons. The IRS were after Andy and continually auditing him because he wrote everything off as a business expense. You see, it all goes back to money.”

Money by Christopher Makos is on at Daniel Cooney Fine Art in New York until June 18.