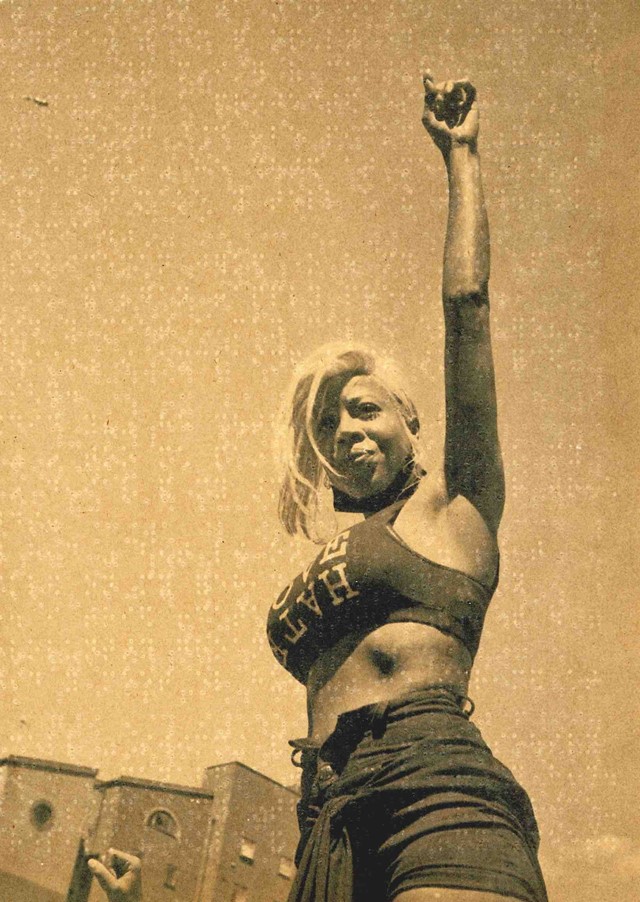

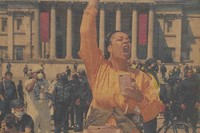

“There was a mood of something coming up to the surface that had been around for a while but [hadn’t yet been] expressed,” says Liz Johnson Artur of London’s 2020 Black Lives Matter protests

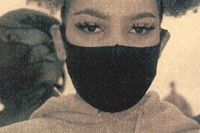

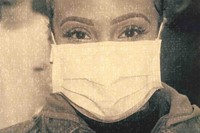

Over the last three decades, Russian-Ghanaian photographer Liz Johnson Artur has been documenting Black life across the African diaspora, particularly in London, where she lives. This week, Tate will publish Artur’s latest photobook, Time Don’t Run Here – a series of images capturing the Black Lives Matter protests that took place in London during the summer of 2020.

Artur has had an eye on community and spaces of resistance for some time. Raised in Bulgaria, Germany and Russia, a trip taken to Brooklyn in 1985 was a formative experience; there, she encountered Black communities for the first time. Artur had a camera, a tool that was new to her, but that she quickly adopted. “Through the camera I had access to people. I could experience things that were difficult for me. That was the beginning,” she says. Much of her work is about the places and people she encounters on her travels. In them, she finds both the spectacular and mundane. She has photographed Russians of Afro-Caribbean descent, legendary Ghanaian photographer James Barnor and PDA, a community of performers, dancers and clubbers in east London.

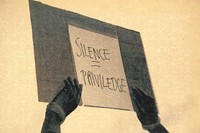

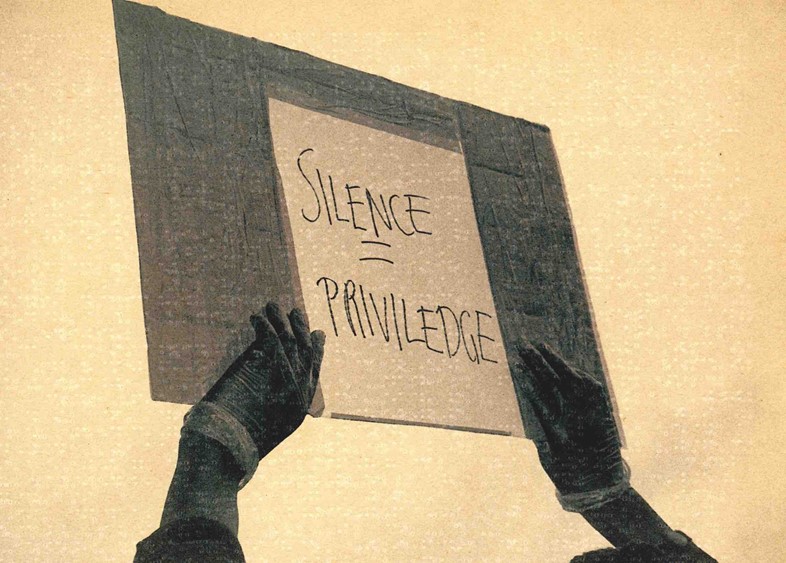

Often the work of a photographer is similar to that of a historian. There’s an element of preservation, a keeping of time. In Time Don’t Run Here, there is a careful consideration of time and its relationship to history, particularly in the context of Black British life. When Artur joined the protests in London, she says, “there was a mood of something coming up to the surface that had been around for a while but [hadn’t yet been] expressed.” It was clear to Artur, however, that it was unsustainable. “It’s hard for people to keep going on in the street when you have to survive in a place like London,” she explains.

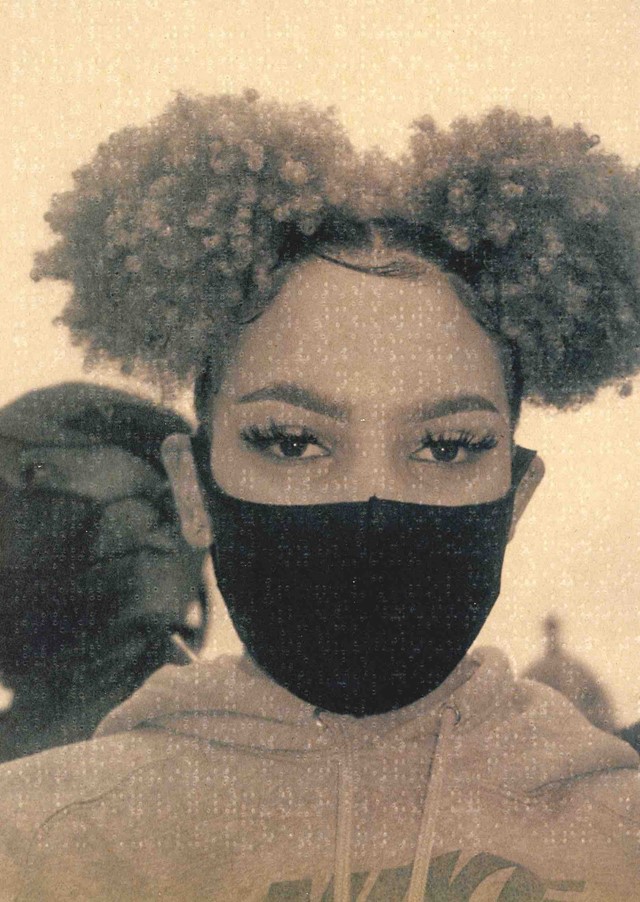

The photographs were a starting point. “I wanted [to create] a document, something that was embedded in time,” she says. She chose to print on braille editions of Iris Murdoch’s 1965 historical novel, The Red and the Green, and Ride Out the Storm by John Harris, published in 1975. Both works narrativise pivotal moments in British-Irish history. The former takes place in Dublin during the Easter Rising of 1916, a rebellion that became a model for subsequent revolutions, while the latter traces the Battle of Dunkirk, which involved the mass evacuation of Allied soldiers across the English Channel from a Nazi-occupied Northern France.

In including the braille, “I could bring in [an aspect of] my work that is quite important, which is a visual tactility,” Artur explains. The tactility of the reference material adds not only a visual but also narrative complexity. The work becomes transhistorical, linked to a long history of resistance, conflict and resilience – there is a timeless, cyclical quality to it. Time don’t stop here, Artur seems to be saying. Time is not running out. We are dealing with a history that is in the here and now, one spanning the past, present and future.

The works in the series are also part of Artur’s Black Balloon Archive, a vast collection of photographs taken primarily in southeast London, as well as New York, Paris and elsewhere abroad. The title derives from the song Black Balloons by soul singer Syl Johnson, who expresses delight at the image of a black balloon against a white sky. Selected works from the archive have been recently exhibited at South London Gallery, Brooklyn Museum and The Contemporary Art Museum St. Louis.

The archive developed naturally; it was an extension of how Artur lived and chose to move through the world. “From the moment I started taking photographs I decided I would take my camera wherever I wanted, to go and see and feel people,” Artur explains. “I wanted to discover Black communities. There was a drive to take pictures because [they] gave me experiences I wanted.”

Over the years, the archive transformed. “It became something of a reference point,” says Artur. “A place where the things I encounter can be put in context with each other.” Her practice of archiving goes beyond preservation, the idea of keeping something safe. It is also about narrativizing and clarifying, while also leaving room for viewers to interpret the work for themselves.

In July, Tate will exhibit works from the collection. Museumgoers will have the opportunity, by request, to view the original prints in the reading room, a stipulation of Artur’s, something she tries to include whenever her work is acquired by a public institution. “It’s why I like to have work in public institutions. It’s public; it should be accessible.”

It’s clear Artur sees photography as a mode of narrative investigation. Where the story goes, however, is up to the viewer. “The whole series is one story. People can read it as they like, as they read the title. They might know what I mean, or they might try to guess what I mean. It’s out of my hands by then.”

Time Don’t Run Here is out on May 12, and is one in a series of four photography books published by Tate.