At the age of 26, Aindrea Emelife has already made a name for herself as one of the most important new voices in art curation. Selected as part of Forbes’ 30 Under 30 cohort last year, Emelife studied at the Courtauld in London before making her mark on the often-rigid art world, where she has focused on breaking down barriers with work that champions inclusivity, female voices, and artists of colour. Alongside curatorial endeavours which traverse the realms of fashion, music and literature, Emelife released her first book A Brief History of Protest Art earlier this year to widespread acclaim. Her latest project, Black Venus, an exhibition at Fotografiska’s New York gallery, celebrates the work of 19 trailblazing Black women artists.

One thing which has set Emelife apart is her talent for telling important stories in confronting new ways – and Black Venus is no exception. The exhibition presents a powerful look at the legacy of Black women in visual culture, investigating the myriad modes of representation they have faced through history – from colonial-era exoticisation and fetishising portrayals, to the present-day reclamation of Black womanhood beyond stereotypes. Telling a multifaceted story of Black women through history, the show encompasses representations across photography, music videos, fashion, social media and film.

“In an age where Black women are taking positions in power, fronting the covers of fashion magazines, and taking up space in all manner of fields and industries, it is a reminder to look back and see how far we’ve come, so we can look to the future,” says Emelife of the curation. Featuring seminal works by some of the most influential Black female artists of our time, Black Venus includes contributions from Zanele Muholi, Deana Lawson, Carrie Mae Weems, Renee Cox, Ming Smith, Mickalene Thomas, and Coreen Simpson. Looking to the future, the show also highlights a new generation of talent shaping visual culture today, such as Amber Pinkerton, Ruth Ossai, and Jenn Nkiru.

Here, in her own words, Emelife talks us through five highlights from the Black Venus show:

Zanele Muholi

“Zanele Muholi has been documenting the lives of Black lesbian, gay, bisexual, transgender and intersex people in townships in South Africa for decades. Muholi’s visual projects are all rooted in their desire to create a Black queer and trans visual history of South Africa. They see their work as a form of resistance, showing lived experiences that have long been marginalised, and even erased. Muholi has turned the camera on themself, too, in striking, theatrical self-portraits that explore the politics of race and representation.

“The work in this exhibition, perhaps surprisingly, is one of the first works by Muholi I came across, and the very first work that I focused on in my academic study at the Courtauld Institute. I’ve always found pageants interesting, as markers and displays of beauty and its canon – and they are further interesting when we understand the historic exclusion of Black beauty in pageant history. Though groundbreaking change has been introduced in recent times with Miss USA, Miss Teen USA, Miss Universe and Miss America titles being held by Black women simultaneously in 2019. In Miss Black Lesbian, Muholi embraces non-heteronormative concepts of beauty by casting themself and posing in full beauty pageant get-up, with visible body hair and tattoos.”

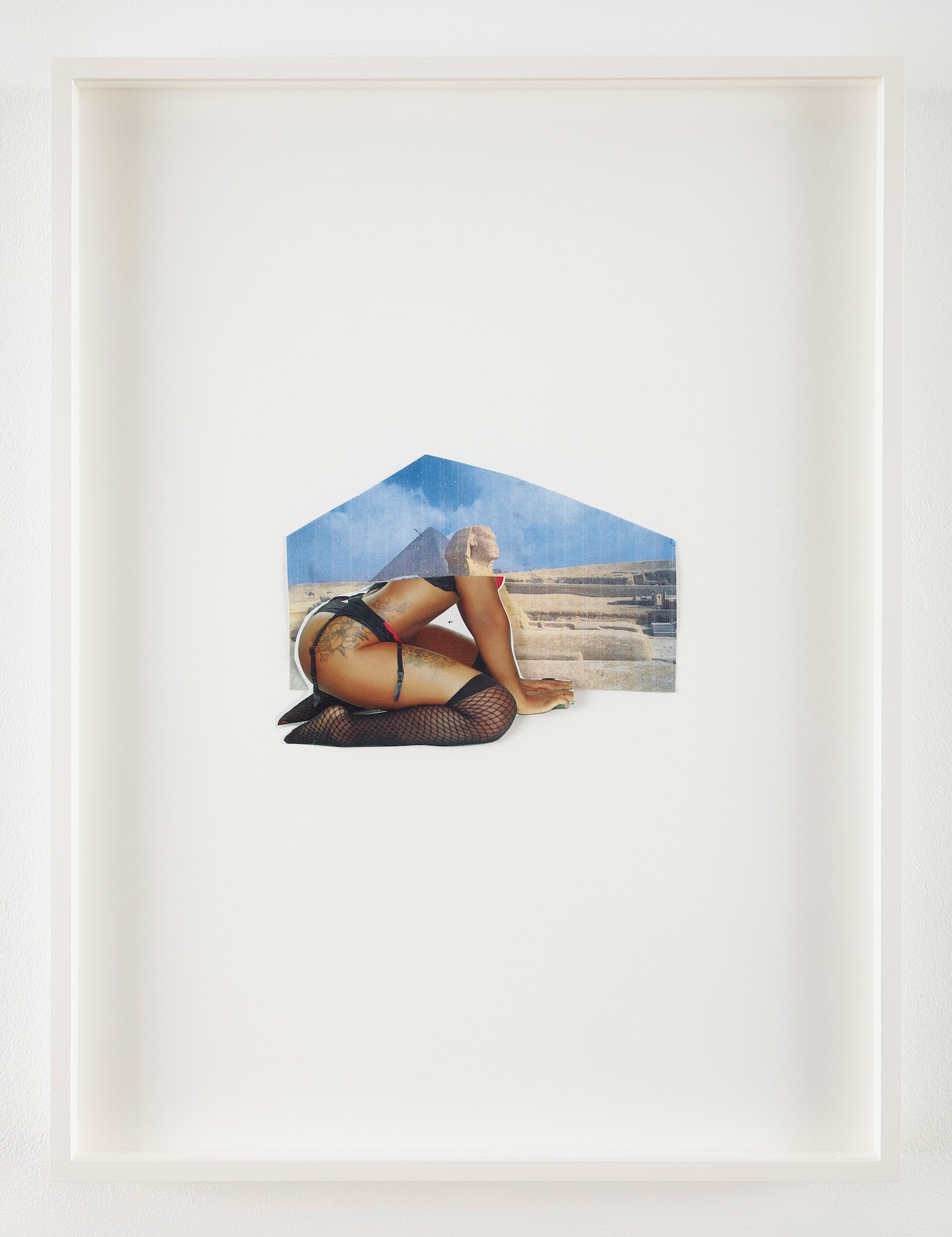

Kara Walker

“Untitled is a preliminary study for Kara Walker’s first public installation in 2014, elaborately titled A Subtlety, or the Marvelous Sugar Baby: An Homage to the unpaid and overworked Artisans who have refined our Sweet tastes from the cane fields to the Kitchens of the New World on the Occasion of the demolition of the Domino Sugar Refining Plant. I came across this work in a book, The Venus In The Dark: Blackness and Beauty in Popular Culture, whilst undertaking my research for Black Venus and thought it was important to include. It’s a work that shows the preliminary stages for monumental art, but also illustrates the importance of found photography and collage, as well as the Black woman in magazines.

“The ephemeral sculptural installation was a 35-feet tall and 75-feet long sphinx in the shape of a woman, coated in 40 tonnes of white sugar donated by the Domino company. In a 2014 interview with Paul Laster, Walker described the sculpture as “a bootylicious figure with something paradoxical about her pose. She’s both a supplicant and emblem of power”. The sculpture inevitably drew comparisons to the Hottentot Venus, especially when visitors to the exhibit posed with it in sexually provocative selfies posted later on Instagram. This earlier draft fuses the head of the Giza Sphinx of Egypt with the bottom of a curvy Black model in lingerie.”

Maud Sulter

“It was important to me that this survey had an international lens, and Maud Sulter is one artist that I feel is deserving of more academia. Les Bijoux (2002) is a series of that comprises nine large-scale Polaroids that present a sequence of performative self-portraits by the British artist. In the work, the artist re-imagines herself as Jeanne Duval, the little- nown romantic companion and muse of 19th-century French poet Charles Baudelaire. Born in Haiti, Duval was an actress and dancer of mixed French and African ancestry. She was reportedly the granddaughter of an enslaved woman from Guinea in West Africa, sent by her owners to Nantes in western France to work in a brothel. In addition to Baudelaire, Duval was a muse to several artists, including Gustave Courbet and Édouard Manet.

“Sulter produced a considerable amount of research on Duval, for which she travelled widely and read extensively. She was particularly interested in the lack of knowledge surrounding Duval, as with so many Black women throughout history. It is perhaps this interest that secures my affinity with Sulter. I have been fascinated by the artist for so long, avidly reading, working with the Estate and recently acquired some out-of-print poetry books by Sulter from Reference Point library at 180 The Strand. It was a joy to be able to present this work in a new way for this exhibition. Inspired by Sulter’s emphasis on disappearance and projection, the idea of the installation – which presents the photographs as a slide reel, each photograph disappearing and reappearing – is to capture this sense of absence, presence and haunting. In addition, audio can be heard reciting poetry from Sulter’s As A Black Woman performed by Yomi Adegoke and myself.”

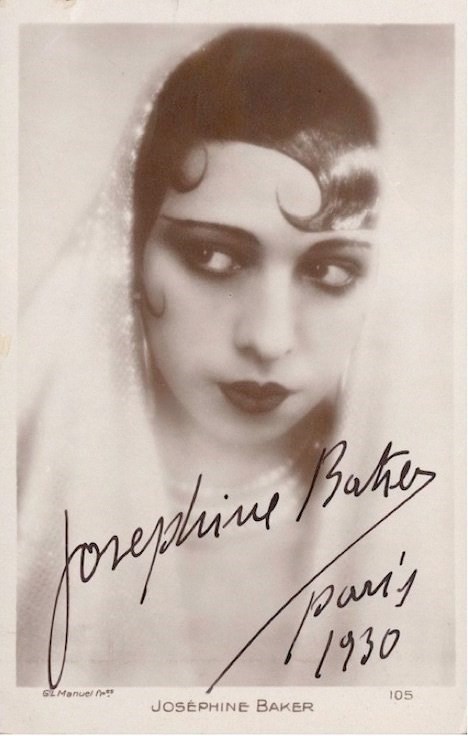

Josephine Baker

“In 1925, Josephine Baker, an American dancer from Saint Louis, Missouri, made her debut on the Paris stage in La Revue nègre (The Black Review) at the Théâtre des Champs-Elysées, wearing nothing more than a skirt of feathers and performing her danse sauvage (savage dance). She was an immediate sensation in Jazz-Age France, which celebrated her perceived exoticism; quite the opposite of the reception she had received dancing in American choruses. In this photograph, Baker is seen dancing in a similar costume with spiked cone details. Her dance style often veered in between sexual and comical, consciously satirising the limited view of Black beauty of her Western audiences. Ernest Hemingway called Baker ”the most sensational woman anybody ever saw – or ever will.”

“The sexualisation of the Black female body continues with the white European interest of Josephine Baker. In contrast to the stereotypical image of the mammy depicting Black women in the United States, Europe developed another one which we may call the Jezebel. According to Merriam and Webster dictionary, a Jezebel is an “impudent, shameless, or morally unrestrained woman.” Josephine Baker perfectly portrayed that cliché when she came to France in the middle of the 1920s.

“Baker embodies an important question for me – why is a woman’s appreciation for her body, and her astronomical levels of self-confidence, painted as indecency and immorality? We want to simultaneously frown upon and marvel at the exhibitionism of pop stars of today, and this conundrum existed in full force in the way Baker was received in America and Europe. Josephine Baker’s exaggerated movements and funny faces played with the racist belief that Black people were “primitive and less civilised”. Self-awareness is thus used as a tool to challenge race prejudice.”

Mickalene Thomas

“Mickalene Thomas is one of the first artists that helped form the idea of the exhibition in its beginning stages. Her practice, at its core, looks at the reclamation of the Black female body and is so integral to the narratives I wished to explore in this exhibition. Thomas’s working method consists of constructing elaborate photo shoots complete with hair, make-up, and wardrobe, which have been likened to high fashion editorial shoots in their complexity.

“In 2009, she began experimenting with incorporating video records of these events with the resulting works, such as in the diptych in the exhibition. “I wanna be evil, I wanna be mad,” croons Eartha Kitt, “But more than that, I wanna be bad.” The lyrics heard in the video explore womanhood liberated from the gendered expectations of purity and fragility. This same theme is echoed in Ain’t I A Woman, an 1851 speech by Sojourner Truth that shares a title with this work, in which she challenged notions of how women are defined and affirmed, and that African American women ought to be included in the women’s rights movement.

“Building on this legacy, Thomas portrays women who ‘are presenting to me, through their lens, how they want to be represented’ – in this case, Keri, a trans woman, posing and dancing to Kitt’s song. Also featured in this is Mickalene Thomas’ mother. This film is a newly-created piece for Black Venus, which sees Thomas revise her earlier 2009 Ain’t I a Woman series and loop the characters into a continuous reel.”

Black Venus curated by Aindrea Emelife is on view at Fotografiska New York until 28 August 2022.