Celebrated in a new book from Baron, the Japanese artist was a pioneer of homoerotic art in Japan – and his work is especially resonant today

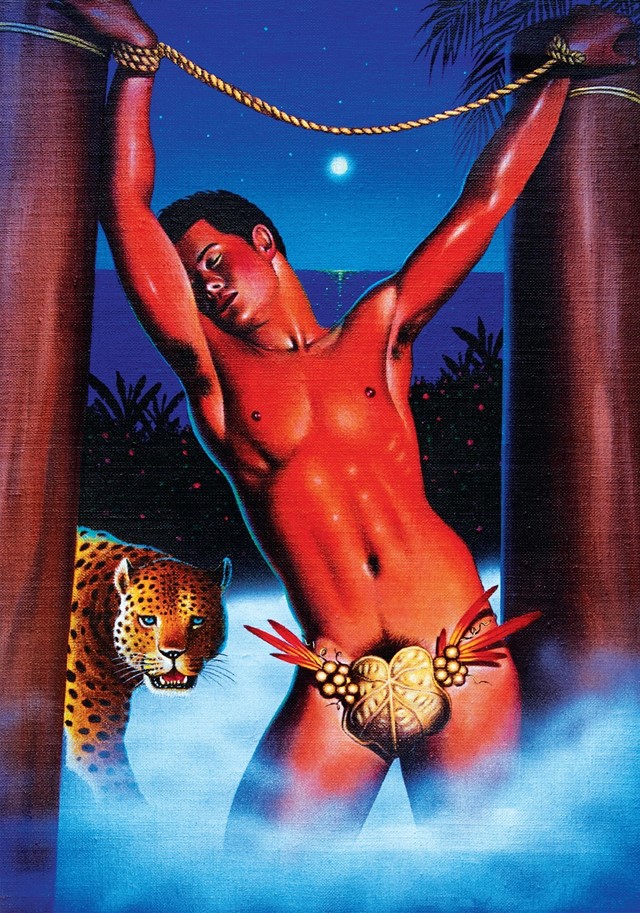

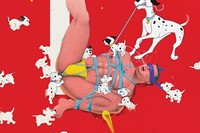

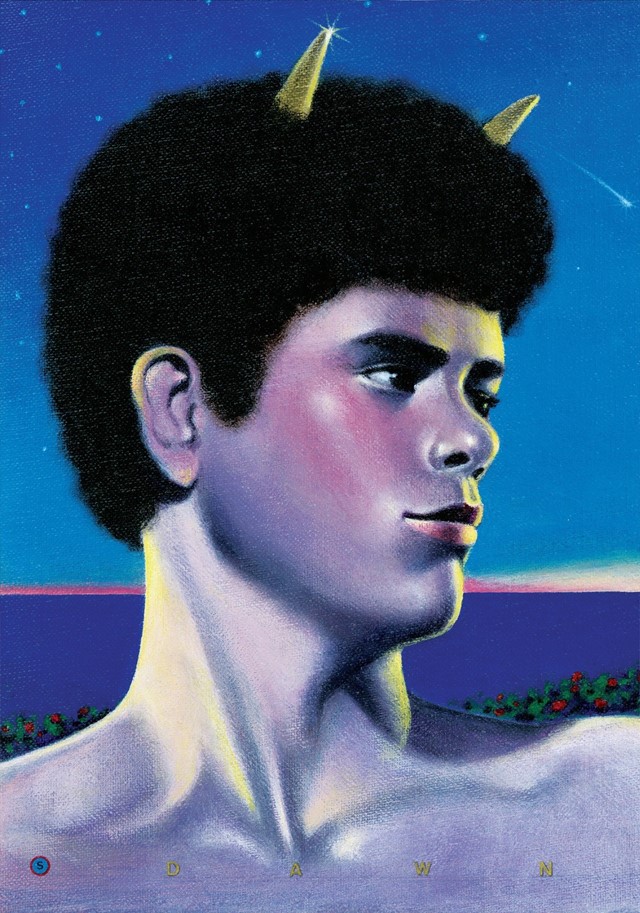

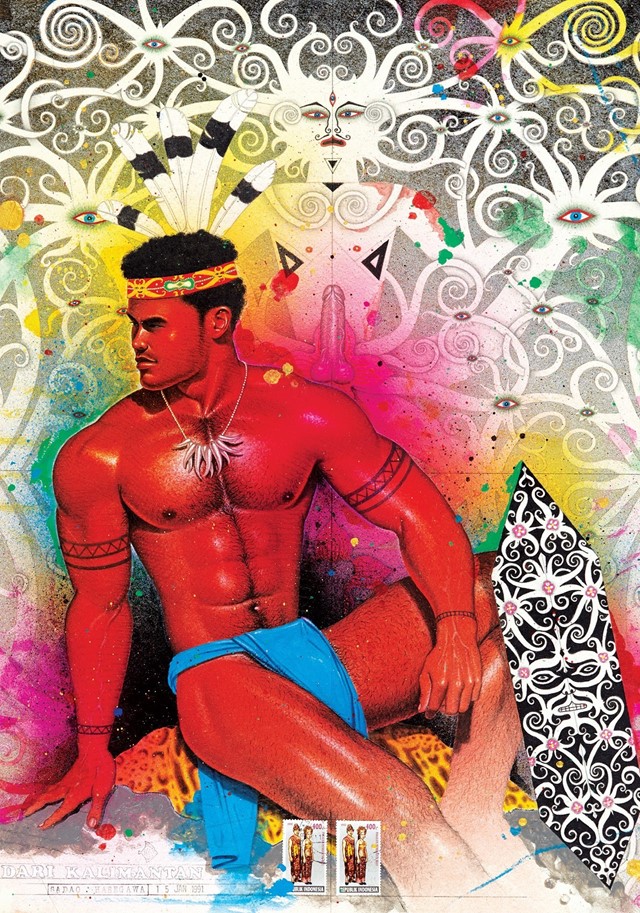

One of Japan’s greatest homoerotic artists, Sadao Hasegawa (1945–1999) transformed the landscape of fetish art with his singular style. Fusing the iconic male physique archetype popularised in the west with elements of Asian, African, and Buddhist art – then adding a splash of BDSM and death for good measure – Hasegawa’s work is infused with a unique blend of mysticism, sensuality, and techno-pop spectacle.

“Sadao Hasegawa was the first to embrace a globalised form of erotic art, and his work is very resonant right now because we are seeing this moment in pop culture in which ‘boy love’ TV shows like Heartstopper have become a huge phenomenon in Southeast Asia, and also globally,” says Dr Thomas Baudinette, who wrote the introduction to Sadao Hasegawa (Baron), the first book of the artist’s work published since his tragic suicide in Bangkok at the height of his career.

Born in the Tökai region of Japan, Hasegawa travelled to India in his 20s and taught himself to draw – a practice he would master making work for Japanese gay magazines including Barazoku, Adon, and Sabu. Deeply immersed in Tokyo’s flourishing nightlife culture, Hasegawa created luminous magazine covers and illustrations for erotic stories that swept readers away into a fantastical world; one that effortlessly combined the delectable machismo of Tom of Finland with Southeast Asian religious iconography.

“Hasegawa was responding to 1950s postwar Japanese culture, where there was both a flourishing of homoerotic because of the lifting of censorship with a heteronormative reaction partly installed through the US occupation,” says Dr Baudinette. “There was a flourishing of the ‘perverse press’ – small magazines circulated somewhat privately focusing on sadomasochism and homosexuality, Japanese illustrator Mishima Go, founder of the sadomasochistic magazine Sabu, being the most famous example.”

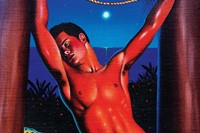

By the 1970s, an emerging mainstream gay culture began to take root just as Hasegawa embarked on his career. His first solo exhibition, Sadao Hasegawa's Alchemism: Meditation for 1973, brought together painting, collage, and sculpture works; five years later he began contributing to Barazoku and never looked back. In the 1980s, he began travelling to Bali and Thailand, incorporating elements into his work, and creating a hallucinatory dream world of Eros and Thanatos.

“Hasegawa became interested in their religious artistic traditions, but he was also going across a broader phenomenon on behalf of Japanese gay men who had travelled to Thailand to participate in a sexual economy that emerged after the Vietnam War,” says Dr Baudinette. “His engagement in queer life shifted his artistic traditions and he began to experiment, moving beyond photorealistic homoerotic art that had become the norm in Japan to this technicolour hyperreality that speaks to late 1970s psychedelia. Hasegawa began pushing boundaries of homoeroticism and desirability.”

Focused on challenging the bourgeois patriarchal constructs of Bubby Era Japan, Hasegawa developed his own style that drew upon pre-war Japan’s decadent tradition of “erotic grotesque nonsense.” He also maintained his nation’s spirit of isolationism, refusing his work to be shown in international galleries. Throughout his career, Hasegawa was committed to exploring Asian masculinity through a queer gaze to reclaim its power from a culture that framed homosexuality as failed manhood.

By working in niche magazines, rather than trying to infiltrate the art world, Hasegawa established legitimacy on his own terms – and eventually the art world caught up. “The magazines provided a much-needed space, motivated in part by economics but also taking inspiration from similar moves in the United States and Europe that created spaces where men could connect with each other,” says Dr Baudinette.

“It was significant because it appeared in mainstream bookstores and provide an opportunity for people to meet before dating apps. Artists could share their vision of homoeroticism and it played an influential role in the ways in which desire is shaped and understood up to the present day. I think this is why they became such an important space to Hasegawa – the mainstream artistic community did not engage with any of it. It’s only in the last ten or 15 years that we’re seeing Japan’s artistic establishment finally recognise the huge homoerotic tradition on Japanese art.”

Although Hasegawa is no longer with us to see his work celebrated, but his extraordinary art lives on, providing inspiration for a new generation of young queer artists working today. “What is most exciting about Hasegawa’s work is that it is so hybrid – Japanese erotic art embedded in a transnational space that responds to western beefcake and Southeast Asian religious imagery,” Dr Baudinette says. “I think that is significant in today’s world, where the community is becoming more globally connected. Hasegawa shows us what Asia can teach us about homoeroticism. He’s a cosmopolitan thinker who is incredibly relevant right now.”

Sadao Hasegawa is published by Baron, and is available to pre-order now