Featuring works shot in Merseyside between 1978 and 2001, Tom Wood’s latest exhibition captures a time of deindustrialisation, unemployment and unrest under Margaret Thatcher’s premiership

“Every day is Saturday” wrote the Liverpudlian poet Paul Farley in his book The Mizzy. The words inspired the title of Tom Wood’s new exhibition, currently on at the Centre de la Photographie de Mougins, north of Cannes. Assembling the artist’s works created in Merseyside between 1978 and 2001, the exhibition captures the atmosphere of stagnation in the North under Thatcher’s government – a time of deindustrialisation, unemployment and civil unrest. “Every day is Saturday when no one has a job,” Wood tells AnOther.

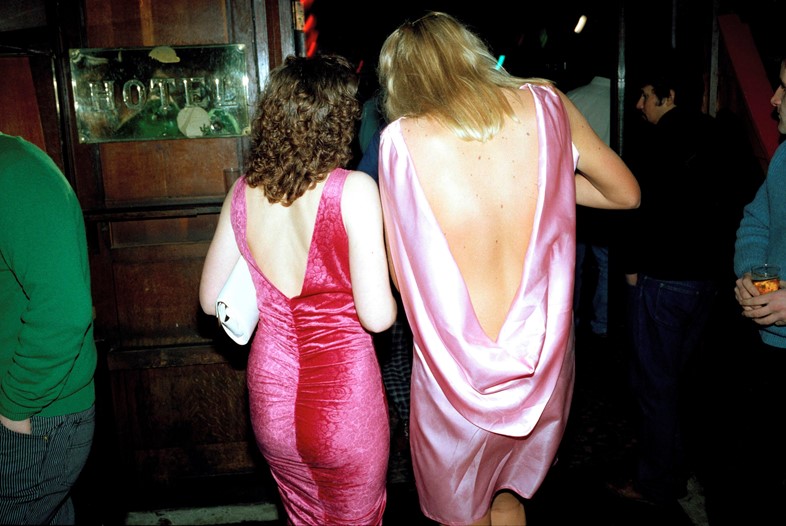

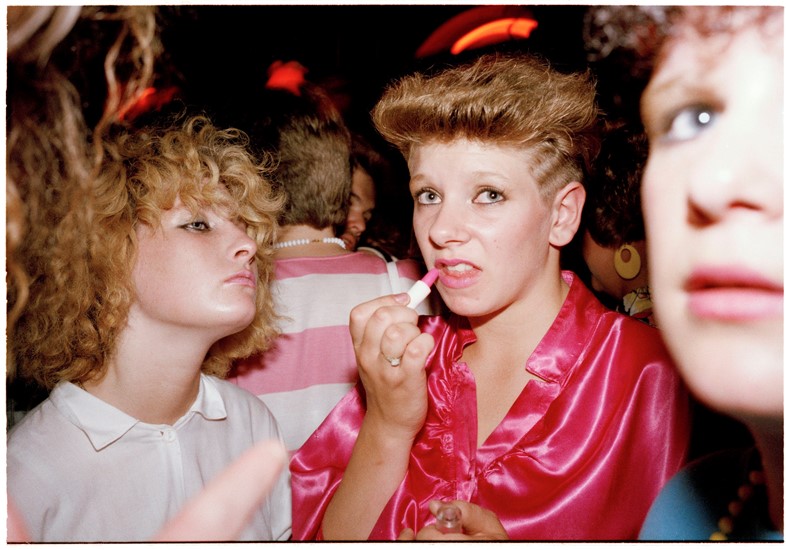

Born in 1951 in County Mayo, Ireland, Wood was raised by a Catholic mother and a Protestant father, which unsurprisingly created familial tension. The family moved to England in the early 1970s, where Wood trained part-time in fine art at Leicester Polytechnic before moving to New Brighton, Merseyside in 1978. Aged 28 and recently married, he quickly befriended the locals who invited him out to the Chelsea Reach club, a venue that sparked his creativity over the next decade and resulted in the colourful and sometimes licentious series Looking for Love.

“On Monday nights Chelsea Reach club was free, so that’s when it was busiest. It’s when people could afford to go out.” A hotspot for disaffected youth, the club was characterised by indoor smoking, records by Wham, the New Romantics, hair-sprayed mullets, electric eye shadow and amorous fondling in the dark (which Wood often caught on flash). To the locals, the young Wood sporting his Leica camera became known as ‘Photie Man’.

Rather than photographing inconspicuously from the corners of the club, Wood daringly shot from the centre of the dance floor. He did this regularly between 1984 and 1987, when the alternative scene began to flourish in Liverpool and the surrounding areas. “In the end, it became too hard to keep photographing the nightclub. It was pitch black and really loud. If you shot with flash in someone’s face, they’d want to punch you. Trying to explain yourself to a drunk person when it’s noisy wasn’t easy. It was hard work.”

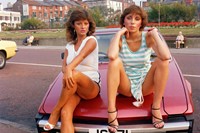

Wood turned his lens beyond New Brighton and chronicled the idiosyncrasies of daily life in and around Liverpool and Merseyside, concentrating on the local working-class communities who frequented the football stadiums, markets, pubs and parks. Inadvertently, the artist who had once trained to be a painter taught himself photography to visually distil youth culture in Thatcherite England. Although regularly compared to documentary photographers like Martin Parr, to this day Wood denies any intention to adopt a political or social angle: “I wouldn’t describe myself as a documentary photographer. I never approached my work thinking about the social issues at that time.” Wood is more concerned with formal qualities: angles, framing, colour and light. “I think about what makes a great photograph.”

Nevertheless, in the early 1990s, Wood received a commission from the Documentary Photography Archive (DPA) to capture the closure of Birkenhead’s Cammell Laird Shipyard, an event that was deeply felt by the community, triggering strikes and leaving tens of thousands of men unemployed. “The whole town of Birkenhead was built around this shipyard. It employed something like 40,000 people.” The series, Cammell Laird, centred on large-scale colour portraiture and interior shots of the working space. Without heroising his subjects with contrived sentimentality, the portraits capture each individual worker with dignity. “I often shot their portraits in their last week before being made redundant. Most of them had been working there since school – their fathers and grandfathers had worked there before them. I see the portraits as powerful and sad, but I also wanted to do the men justice. My sympathies were with them.”

Ironically, although Wood spent much of his career photographing people on the street, he describes himself as “incredibly shy.” He’s against the idea of aggressively capturing someone’s portrait without a degree of reciprocity. He regularly gives back to his subjects, sending them prints and photographs in exchange for their trust and consent over time. “I’m very careful with my work. A lot of my photographs have never been seen. After all, these were the people I lived amongst.” One of his great admirers, Martin Parr once said to him “You’re too nice to be a photographer.”

Underpinning Wood’s practice is a genuine fascination and respect for his own community. Although he admits to always feeling like an outsider, the fact that many Liverpudlians have Irish descent offered Wood a degree of acceptance. “In England, we were always isolated for being the Irish family in England. But in Ireland, we were also isolated for being Protestant.” This sense of belonging and unbelonging has arguably shaped his perspective, giving him the ability to perceive the residents of Merseyside with clarity and compassion. “I’m really interested in my subjects and the people around Liverpool – they’re very tolerant, friendly and humorous,” he says. “I couldn’t have made those pictures anywhere else.”

Every day is Saturday by Tom Wood is on display at the Centre de la Photographie de Mougins in France until October 16, 2022.