“Too many people in Romania as a whole do not recognise their sexuality publicly,” says Alin Kovacs, whose new photo series aims to make Bucharest’s young queer creatives visible

Even though homosexuality was decriminalised in 2001, marriage and civil partnerships for same-sex couples are still not recognised in Romania. But the country’s LGTBQ+ community remains defiant; on July 9, an estimated 10,000 people took to the streets for Bucharest Pride, ahead of planned legislation that could ban ‘gay propaganda’ in schools, censor the media, including films, and place restrictions on marches and other public events.

Alin Kovacs’s new photo series, In Transition: Queer in Bucharest, aims to make the LGBTQ+ community – that is so often regarded as invisible in the eyes of the state – visible. Set against the decadent backdrop of 19th-century houses with abundant linden, jasmine and roses growing nearby, or the verdant parks of the city, six young Romanian creatives – musicians, curators, students and performers – pose for Kovacs’ camera. “A lot of them still hide their identity, unfortunately, due to general stigma they would find on the street, at work or within their families,” he says. “So I thought that any sort of small effort towards having their voices heard could help.”

Kovacs is a self-taught photographer from Bucharest – he now splits his time between the Romanian capital, London and Warsaw – and although not queer himself, the project was an important endeavour. “[I hope] that it will encourage individuals from more conservative societies or backgrounds to accept themselves,” he says. “Living close to who you are is essential in life.”

Below, Kovacs interviews six LGBTQ+ creatives from Bucharest about the city’s queer scene, their coming out stories, and the journey to self-acceptance:

Robert, Curator

Robert, does working in art make you feel more comfortable about your sexuality?

It’s a sure thing that in the art world the level of acceptance is higher, but even here, you have your right wing supporters. Fortunately, in the art world they are a minority. Yes, it is an advantage for me working in the art world, but I think things would’ve been much more complicated if I worked in sports or patriarchy-dominated groups.

Do you think there are still a lot of people in Bucharest that are gay and choose to hide their sexual inclination?

There are people still hiding or denying their sexuality everywhere in the world, not only in Bucharest. In small conservative communities, small villages or cities, heteronormativity is the only choice.

Maria, Musician

How are opportunities distributed for queer artists on the local music scene?

The great thing about the queer community and the music scene here is that a lot of us support each other and lift each other up, especially when it comes to work opportunities. We always recommend other queer artists to the people we work with, and I really have this sense of a network and community among my peers. However, a lot of us still have pretty precarious lifestyles, as the opportunities provided by the mainstream cultural sector are scarce, especially for independent and emerging artists.

Did you see an improvement in terms of acceptance for artists from the community over the years?

I’m not sure acceptance is what a lot of us are looking for. We’re definitely looking for safe spaces, and there have been very strong and beautiful attempts by activists and queer event organisers to provide that either by organising constant specific events or by supporting full-time social spaces dedicated to queer people. Unfortunately, living at the intersection of queerness and precarity means that a lot of these projects – especially trying to rent a space full time – are constantly vulnerable to dissolution either because of the homophobia of neighbours or landlords, or because of the financial difficulties of life under capitalism. But queer people here are constantly fighting to reclaim space for our safety and communal joy, and the growth of the scene has been exponential in the past few years.

Octavia, Student

Octavia, congratulations on coming out a year ago. How did your family and friends get the news?

Thank you so much! Coming out as non-binary was a peak in my journey of understanding my identity. Parts of my biological family, along with my friends, were very supportive because, fundamentally, I am still the person I have been before – I just had to explain my intrinsic queerness. Other people related to me did not take this news well, and unfortunately, I was forced to cut ties with them. In a way, I think it’s beautiful how queers like me get to choose their own family.

What would you advise anyone thinking about coming out about the process and decision-making?

Coming out is a very sensitive and subjective topic, if you ask me. Circumstances can drastically differ from person to person. What helped me specifically was to asses everyone around me’s view on queerness, both directly and indirectly. Once I knew someone’s stance on the subject, I would just see if there was any worth coming out towards that person at all. Always assess your social territory and think in a pragmatic manner.

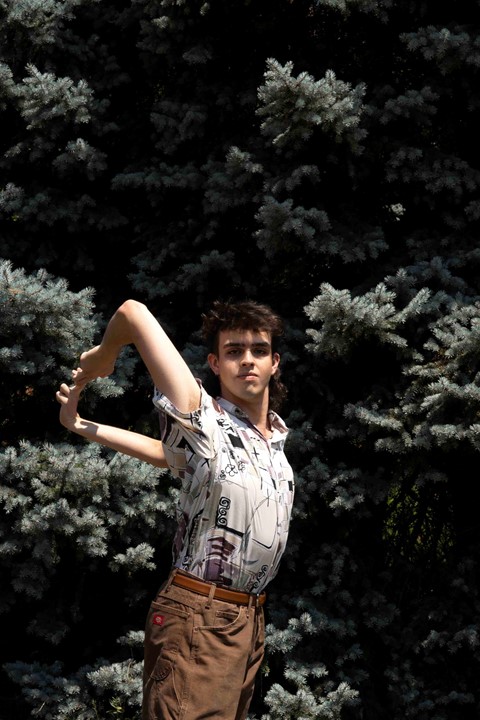

Geo, Student

How hard is it for someone from the LGBTQ+ community to find their way in Romanian society?

It is tough. I have been living in London for the past two years, which now allows me to have a term of comparison between these spaces. My story begins in a small town in the middle of nowhere, later on following my move to Bucharest, the capital, at around 16 years old. So; being a queer person living in the countryside versus being a queer person living in a metropolitan city. I experienced both – in a highly conservative and post-communist country.

I never met an out queer person for 16 years. This not only made me think that there weren’t other people like me, but also had a huge impact on my self-esteem. The representation of queerness is non-existent, even in urban areas.

There are small communities of queer people in Bucharest, yet it seems to me that barely anyone really lives freely, even inside the communities, due to the fear of being judged or harassed. And most of the time these groups become private and out of reach, but I was lucky enough to look in the right direction and find one when I moved to the capital.

What does loving freely mean to you?

Forms of love can only feel free if we are willing to understand each other. It is hard coming out of our shells and diving into the unknown, but promising at the same time. It is crucial that we leave prejudices behind. In this way, we can not only learn more about each other, but actually empathise with each other. Free love happens in places where people allow it. It’s hard to navigate through love in a space where that is not possible. You become hyper-vigilant.

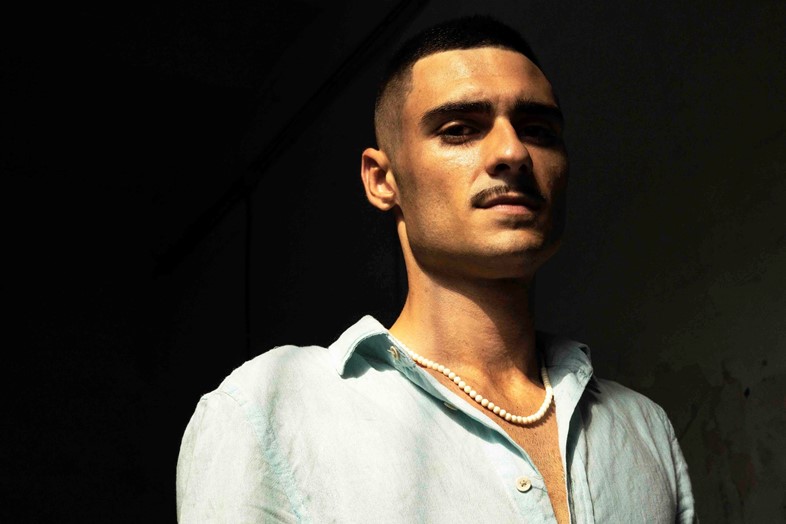

Bogdan, Student

Bogdan, it was very brave to express your sexuality so early. Was it a slow process or did it happen all in a sudden?

I feel like I always knew my true identity and sexuality somehow. When I turned 11, all the lines connected and it was all clear to me. It’s a known fact that these things are sometimes hard to find out. I feel like we all try to deny our true identities because we are afraid of other people’s reactions, but the best way to deal with this is fully accepting yourself.

Considering that you commute to Bucharest daily. What are the reactions that you get?

It depends, some people just stare, other people feel the need to say something. Some take pictures without my consent, others come and compliment me. I think the most reactions that I’m getting are from men, and I’m talking about the negative ones. For me, it’s clear that they are very insecure and they don’t know how to act when they see a fully confident and proud person, but that’s not an excuse. I think we all should work on our problems, not throw them on other people.

Nanci, Performer

Do you think there has been any progress on how people from the community are accepted in Romanian society?

I think some societal changes happened in the last ten years. Still, they mostly took place for LGBTQ+ people who are invested in assimilation and respectability. Take for example those working in corporations who benefit from the privilege of a secure workplace, where strategies of diversity and inclusion are in place. Yet, this diversity and this inclusion is only partial, since it becomes a matter of respectability, with integration being based on class signifiers.

It is about LGBTQ+ people that want to be integrated in a mainstream Romanian society. On the other hand, the queer community wants a more radical change, going in a different direction. We dream of social transformations, where we do not need to change ourselves in exchange for acceptance.

What are the first two improvements queers need to see in their everyday lives?

The biggest aspect is the one you have to deal with in day-to-day interactions – there, you truly see the degree of acceptability. I believe the biggest changes have to happen with the violence, harassment and hate we experience on the street. Yet, this is not going to happen too soon, when the state prioritises funding towards the church and doesn’t provide access to sexual and feminist education.

For me personally, it’s very hard to dress freely and go out in society. And when I do it, I am stared at in a judgmental way wherever I go. It’s a constant stress to not be able to enjoy a normal day of your life in public.