“I’ve had many people tell me my work replicates the male gaze. I find this ridiculous,” says the American image-maker, who regards her work as a form of queer and feminist activism

In the essay Visual Pleasure and Narrative Cinema (1975), the feminist theorist Laura Mulvey coined the ‘male gaze’, arguing: “in a world ordered by sexual imbalance, pleasure in looking has been split between active/male and passive/female.” This idea is so entrenched in feminist thought – and our culture more broadly – that still today, nearly 50 years since the publication of Mulvey’s essay, the female nude remains a contested symbol.

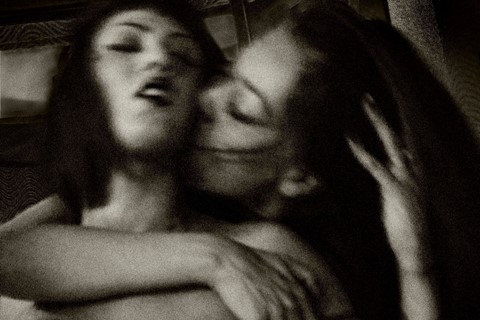

American photographer Renée Jacobs explores this tension directly. Her work – which centres on expressions of female sexuality – is regularly censored by gallerists and curators, many of whom believe her work slips into the sullied realms of pornography. But by gatekeeping what can be defined as ‘high art’, museum and gallery professionals have opted for desexualised expressions of female and queer desire, which ultimately repeats the historical marginalisation and silencing of the LGBTQ+ community. “I’ve had mentors tell me that if I publish certain images my career will be over, or publishers who have walked away from projects after loving and supporting my work for years. There is something about authentic expressions of female desire that scares people.”

For Jacobs, sensuality and sexuality exist beyond the reductive binary of active male versus passive female. In contemporary terms, the ‘female gaze’ denotes an active mode of voyeurship, but Jacobs would prefer to change the semantics altogether. “I really think that terms such as male gaze and female gaze are fraught. If it was up to me, I would replace them with the empowered gaze and disempowered gaze.” For Jacobs, such labels fail to encompass the diversity of sexuality, especially those of the queer community and the individuals whom she photographs regularly. “For me the most important thing is to give the woman in the photograph the agency, allowing her to express and experience what she desires. Who are we to tell her ‘no’?”

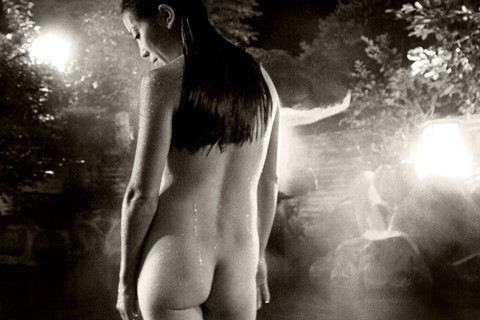

Jacob’s work undeniably raises questions about social attitudes towards female desire, which often render self-possessing and unashamed female sexuality taboo. “Longing to me is the most important component of my work. My work is about listening to these women because I didn’t have the voice to express my own longings for so long.” Underpinning her work is a motive to give visibility to what is repressed, to acknowledge desires that are unmediated by – or even indifferent to – the male gaze.

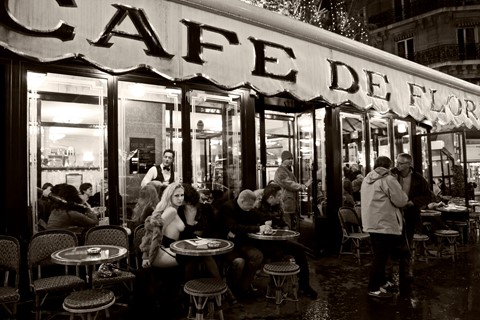

Yet ironically, her work is often trapped in the politics of the male gaze. For that reason, some of her works were recently removed from the exhibition seeingWOMEN, shown alongside Helmut Newton’s work at FotoNostrum Gallery in Barcelona. Jacobs tells AnOther “a straight male version of the female nude is accepted and elevated by the art world, whereas photographs of authentic female desire by women artists are threatening … the art world tends to only reference lesbianism when it is the fantasy of a male photographer.”

“I’ve had many people tell me my work replicates the male gaze. I find this ridiculous,” Jacobs says. She also rejects the idea that her female subjects are merely internalising the male gaze, countering the arguments of John Berger in his influential Ways of Seeing: “Men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at. This determines not only most relations between men and women but also the relation of women to themselves.”

When we consider the cultural impact of queer artists such as Robert Mapplethorpe in the 1980s, who gave visibility to same-sex male desire, it is curious that the art world still finds representations of lesbian and female desire – when directed by women – uncomfortable. Why is the critical and intellectual framework given to Mapplethorpe not denoted in the same way to women artists? Why is it taken less seriously? Jacobs regards her work as a form of queer and feminist activism against such moral impositions, the same societal judgements that prevented her from coming out as a lesbian earlier in life.

So how can we rethink and expand notions of the female gaze? Jacobs proposes “take the ‘gaze’ out of the equation and substitute it for a mirror: give the woman the space and power to see her authentic expression of sexuality reflected back to her – without accusing her of performing for the male gaze.” By doing this, Jacobs places her female subjects in a position of control and power – what she would call the ‘empowered gaze’.

Whether the male gaze can ever truly be escaped is still up for debate. However Jacobs proposes a more elastic notion of the gaze, one that reflects the fluidity of sexual experiences today, moving beyond the heteronormative model once outlined by figures such as Mulvey. For Jacobs, we have already taken positive steps in that direction. As she says, “women are not shaming themselves as much, and not allowing themselves to be shamed – and that’s a fantastic thing.”

seeingWOMEN by Renée Jacobs at FotoNostrum Gallery in Barcelona ran from 21 May - 24 July 2022.