“There was a photographic innocence back then. People were charmed by the camera,” says the American photographer, whose two new Steidl books capture New York, Los Angeles and New Orleans in the 1970s

In 1973, Mitch Epstein moved to New York to study at Cooper Union with Garry Winogrand, one of the most esteemed photographers of the post-war era. Then just 20 years old, Epstein’s camera became a vehicle to discover the city, which by the turn of the decade had become a sprawling metropolis marred by economic collapse, crime and growing inequality.

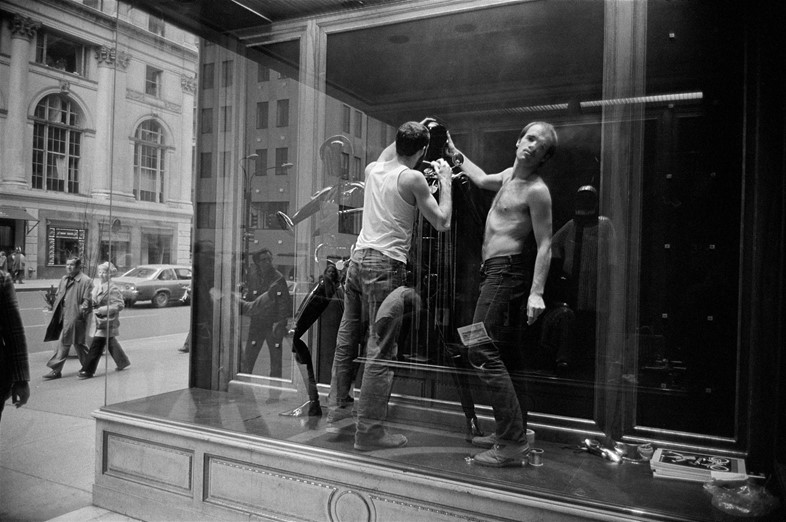

Although Winogrand predominantly taught his students to experiment in the darkroom with black and white photography, Epstein opted for colour photography using Kodachrome film and a handheld 35mm camera. “The world is in colour so why not photograph in colour?” he tells AnOther. “I was interested in its psychological and emotive properties – those particular qualities that I could harness in the picture.” Inspired by the approach of his teacher, Epstein fearlessly immersed himself in the chaotic streets of New York. But like Winogrand, he firmly rejects the label ‘street photographer’. “I don’t think of myself as a documentarian, but [there’s] no doubt I draw on those traditions.”

Indeed, Silver + Chrome, which documents American cities – New York, Los Angeles and New Orleans – captures more than the socio-political idiosyncrasies of urban life in the mid-1970s. Although primarily concerned with form, Epstein subtly evokes narratives beyond each carefully constructed picture frame: a fashionable young woman stands in a telephone box, a crowd of pedestrians gesture towards the sky with gusto. “I understood from the beginning that the photograph is not the thing you are photographing itself. A photograph must always acknowledge its two dimensionality and cannot replicate the three-dimensional world.”

Alternating between black and white and colour shots, Silver + Chrome amplifies the hubbub and dynamism of the city, whereas the photographs selected in Recreation tend to be sparser and more measured in nature, partly because at that time Epstein had begun shooting with a different camera that deployed colour negative film. “I didn’t have the same fluidity, so the pictures became more tableau-like, and the juxtapositions more intentional.” Grouped together largely through the theme of repose and recreation (as the title suggests), they evoke oppositional and unlikely moments: a woman engrossed in a paperback on the pavement outside of a salon, or a man taking a nap on a makeshift bed in a derelict site beneath the recently constructed World Trade Centre.

“The towers were so totemic,” Epstein recalls. “At that time that whole area on the western side of lower Manhattan was in the process of being developed – known as Battery Park City which lay alongside the Hudson River. I was making a lot of pictures in that area. This shot was about intuitively capturing the juxtaposition of things. It was so unlikely that this man was taking a siesta next to his emerald Cadillac, I thought he might be a New Jersey mobster.”

Whether homeless or merely taking a nap, the sheer contrast in scale between the lone, sleeping man and the looming skyscrapers serve as a metaphor for the rising economic disparity in New York at that time, coinciding with the acceleration of Wall Street, neoliberal policies and urban renewal that irreversibly transformed the identity of the city leading up to the 1980s.

In comparison, the 1970s held onto a liberated atmosphere of bohemianism, less tainted by market forces, which is perhaps why so many of us feel nostalgic for that decade in 2022. “The 1970s was a less commodified era. Today there is a conformity through the rapid capitalisation of society which has changed our relationship to art and photography,” Epstein argues. For that reason, he acknowledges that he couldn’t create the same kind of work today – contemporary subjects would be suspicious of the camera and the likelihood it would end up online. Indeed there is something wholly uninhibited about his subjects in Recreation, especially the dancing couple wearing pink shirts and floral flares. “There was a photographic innocence back then. People were charmed by the camera. They didn’t immediately assume you were going to take their picture and do something negative with it.”

Although Epstein regards the democratisation of photography through smart phones as a positive thing, he remains sceptical about what it means for the medium and its future. ”So much work today is derivative. You need to be informed and have a critical eye to understand what makes a strong photograph.” In homage to the teachings of figures such as Winogrand and those who came before, Epstein’s latest work maintains reverence for the technicalities and traditions of photography, reflecting his matured ‘editor’s eye’ and understanding of how to effectively sequence images together. Perhaps more profoundly, his works recall a bygone era and sensibility we have lost to the rampant rise of technology over the past half a century.

Silver + Chrome and Recreation by Mitch Epstein are published by Steidl and are out now.