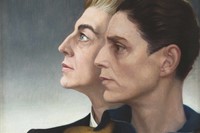

On the first page of Katy Hessel’s mammoth debut book, The Story of Art Without Men, lies a reproduction of a painting by the great American artist Alice Neel; the painting, created in 1973, depicts Linda Nochlin – author of the searing 1971 feminist essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? – and her young daughter Daisy in graphic, swirling paint strokes. The placement of this image at the start of Hessel’s book is of great significance – in 2015, after going to an art fair and realising there was no work made by women on the walls, Hessel launched her Instagram account @thegreatwomenartists. Taking its name from Nochlin’s groundbreaking essay, the account spotlights an eclectic range of art made by women – it now has 287,000 followers, and has spawned a popular podcast of the same (where Hessel has interviewed artists including Marina Abramović, the Guerrilla Girls and Cornelia Parker).

“Would feminist art exist without Linda Nochlin?” says Hessel emphatically, when we meet at a cafe in north London ahead of the book’s launch. “I don’t know … she wrote this at the dawn of the feminist movement and it changed everything.” The Story of Art Without Men, like Nochlin’s essay, is equally radical. Written as a feminist rebuke to EH Gombrich’s The Story of Art – a grey tome widely accepted as the definitive art history bible, which mentioned no women artists whatsoever when it was first published in 1950 – Hessel’s The Story of Art Without Men does exactly what it says on the tin; it expunges men completely from the art historical record.

Across nearly 500 pages, Hessel takes us through art made by women from the 1500s up until the 2020s: there’s the quietly radical self-portraits by Clara Peeters; the brutal, bloody canvases of Artemisia Gentileschi; provocative performance art courtesy of Yoko Ono and Marina Abramović; ballsy YBA art by Sarah Lucas and Tracey Emin; and much, much more. Despite its focus on western art history, the book is decidedly intersectional in its approach to women artists, and there are many new names to be discovered (the cover also lifts its graphic identity from one of the most popular corrective books in recent memory: Reni Eddo-Lodge’s Why I’m No Longer Talking to White People About Race). “[In the past] we literally celebrated the history of patriarchy rather than the history of art,” says Hessel. “And if you’re not seeing art by a range of people, then you’re not seeing society as a whole.”

Violet Conroy: What was your experience like studying History of Art at UCL?

Katy Hessel: I loved it, but the thing is, it was very traditional. My eyes weren’t really open until my final term when I had this amazing visiting tutor and we did this incredible course on art and activism. Suddenly, I learned about people like Ana Mendieta, and the fact that art can actually be used for a purpose. And then I started my Instagram straight after that, because I went to an art fair and had this epiphany that there were no women artists in this entire tent. And so I started the Instagram [@thegreatwomenartists] in bed that night – I couldn’t sleep – and it’s all grown from there.

VC: Like you, I also really struggled with the elitism and the academic nature of studying History of Art.

KH: I mean, honestly. Like, am I the only person who literally can’t read this? Recently I was doing a film for a gallery – I won’t say which one – but they sent me the press release, and I was like, what? When things are described like that, first of all it’s so elitist, but then you can’t even get into it. It’s really important to be accessible, and I love reading Grayson Perry on art, Olivia Laing or Jennifer Higgie because they just say it how it is.

That’s also why I went down the journalism route rather than doing a master’s, because I wanted to write something that would be read by the masses. I don’t care where people get their art knowledge from. I love the story of Tracey Emin, when she was younger, going into a record shop in Margate and seeing David Bowie’s albums and then finding out who Egon Schiele was from that, because Bowie would base all his albums on Schiele. I want everyone to feel like they’re part of this conversation.

“I wanted to write something that would be read by the masses. I don’t care where people get their art knowledge from” – Katy Hessel

VC: When did you first come across Linda Nochlin’s essay Why Have There Been No Great Women Artists? It’s such a central part of the book – do you think your book would exist today without that essay?

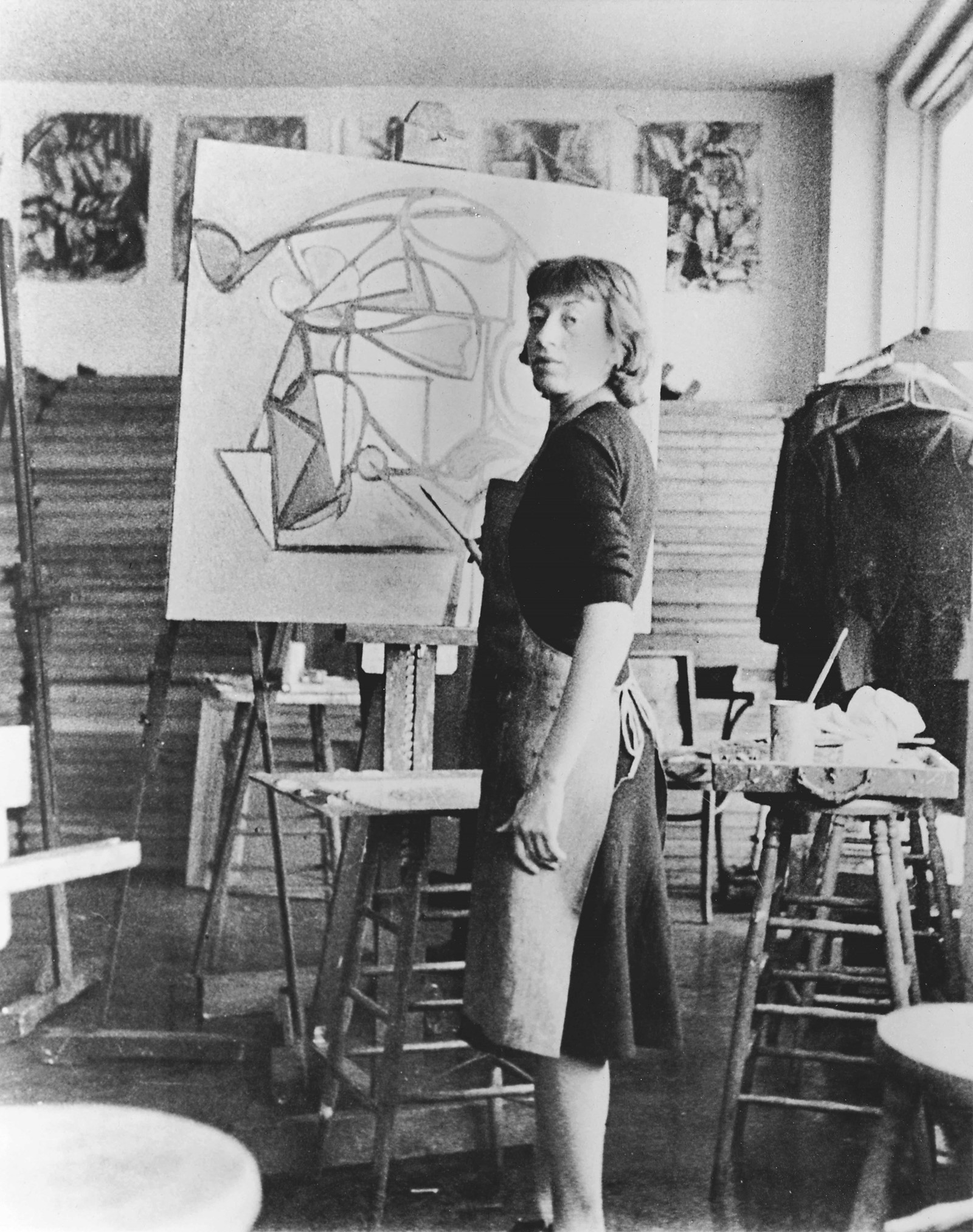

KH: Well, I think the Instagram [@thegreatwomenartists] wouldn’t have existed without that essay because she wrote this at the dawn of the feminist movement and it changed everything. It broke down everything that we know about art before. She was a total pioneer. I first came across that essay when I was at school, but I don’t think it really resonated with me because I was studying such a traditional art historical syllabus. And then I revisited it after university when I was studying Alice Neel for my dissertation, because Neel was great friends with Nochlin and Neel painted her.

I mean, would feminist art exist without Linda Nochlin? I don’t know … at the same time, she was standing on the shoulders of people. I’m standing on the shoulders of people – although the name Linda Nochlin does get thrown about, there are so many people who contributed to it.

VC: So much of what you do is online, with your podcast and Instagram. What made you want to write a book? And do you think books still have the power that they used to?

KH: The power of having a tangible thing, like a book or a diary, is so key in this day and age because it can completely transcend you from this whirlwind that is the internet to something really tangible and also long-lasting. People can easily scroll through my Instagram and have a look at old posts, but at the same time, they’re probably not going to do that. Whereas a book lasts forever and having that is so powerful.

The reason why I started on the internet is because I was 21 and I didn’t have any access to anything. I always loved bloggers, so I was a massive fan of Tavi Gevinson when I was a kid. What I loved about her was that she made fashion accessible. I loved Style Rookie and I loved how it was born on the internet as well as being a magazine. I just think the internet is this amazing, weird place, but it also has amazing corners and amazing communities. And it’s accessible, right? Most people in the west have access to a smartphone and WiFi and the fact that a kid who’s never even come across art history, or stepped inside a museum, can just look at the [@thegreatwomenartists Instagram] page.

VC: Tell me about the choice to expunge men completely from the record? It’s a radical act – was it difficult to keep them out of the narrative?

KH: Do you know what? Because I’m so focused on women artists, I really don’t know anything about male artists. I know them almost through the eyes of women, which is quite incredible. Like, I know that Suzanne Valadon was taught by Degas – that kind of thing. It’s actually quite easy to leave them out. It baffles me as to why women have been left out of the canon. Either it was a conscious decision or they were just ignorant and lazy.

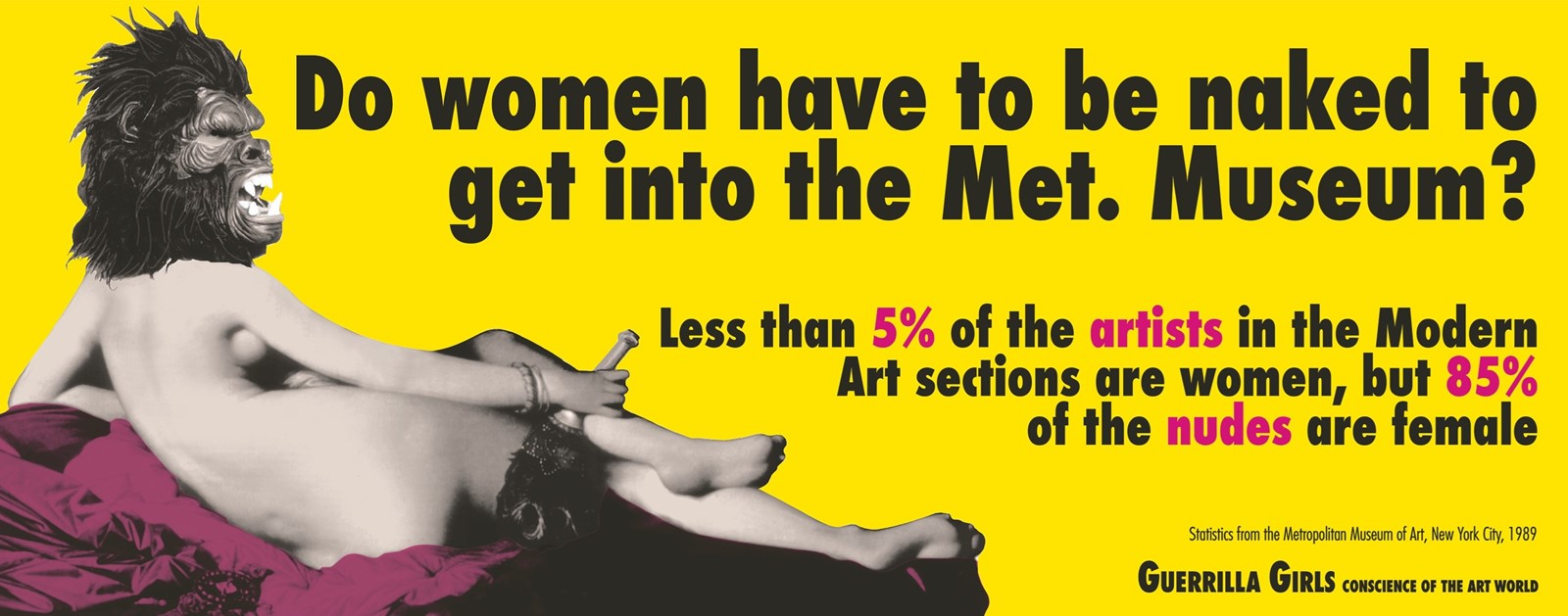

When I realised this, I was like, ‘We’re just missing half the history of art.’ I say this in the Guerrilla Girls section [of the book], but we literally celebrated the history of patriarchy rather than the history of art. And if you’re not seeing art by a range of people, then you’re not seeing society as a whole. I’m not also trying to claim this is a definitive art historical book, because I think that so many people can write similar things. I’d love to read the history of literature without men, for example.

VC: Speaking of history, you write in the introduction that this is not a definitive history since that would be an impossible task. In the book, you often write in the first person – was this your way of reacting against the notion of history?

KH: My first draft wasn’t really written in the first person, and then my amazing editor Helen Conford asked where my voice was. I wanted to have an editor who isn’t an art historian because I really want the book to be read by the masses. One of my favourite books is Olivia Laing’s The Lonely City and the way that she writes in the first person ... for me, it just felt natural. Maybe it is about rebelling against history. Olivia Laing was really groundbreaking in this because, also, up until the 1990s, people never spoke about biography – that was frowned upon. We are in this world now where people want personalised stories. For me, finding out about an artist’s life and their sociopolitical context is a way into their art. It might not be correct, and it might not be the artist’s take but for me, it’s how it helps me understand art.

“It baffles me as to why women have been left out of the canon. Either it was a conscious decision or they were just ignorant and lazy” – Katy Hessel

VC: How important was it for you to make this book an intersectional account of art history?

KH: So important. In the last few years in London, there’s been a lot of corrections taking place and it’s thanks to artists and curators of colour who actually put these amazing shows on. It’s so important also because a lot of errors were made in the second-wave feminist movement and when we look back at the 1970s, they were glaringly obvious. I remember interviewing Howardena Pindell for my podcast and she said it was the white women’s movement – and that’s not OK.

VC: Do you think in your lifetime that we’ll get to a place where women artists will finally be treated equally? And what kind of things need to change to make that happen?

KH: I mean, I’m hopeful, but I don’t know. We’re living in a more inclusive time than ever, but real change has to happen, like urgently. The fact that one per cent of the National Gallery’s collection is still by women, and it’s ‘groundbreaking’ that Frances Morris was appointed as the first female director of Tate Modern in 2016, how Maria Balshaw is still the first ever woman head of Tate ... it’s also not just a women issue, it’s also a race issue, a sexuality issue. There is so much to be done.

VC: I was really struck by how many of the artists in the book inflict violence on themselves, whether physically or metaphorically. Why do you think women artists explore these themes of masochism and self-destruction so much?

KH: I think it’s about being in touch with the body. I don’t even know if it is a masochistic gesture, even though it might appear like that. I interviewed Marina Abramović the other day for my podcast, and she said it’s about being in touch with your body and connecting the mind and the body. Women’s bodies have been commodified and objectified for hundreds of hundreds of years and so it’s almost like a fight back from that. You sort of turn the body on its head and you use it as a form of power.

VC: You’ve mentioned that you’d like to write more books in the future – what kind do you want to write?

KH: Essays about art and society and how art can be a force for change for society, and how it can also relate to our world. A bit like what I’m doing with my Guardian column, which is about getting an artwork and relating it to the news agenda. I don’t think I’m going to do a book quite as ambitious – it was so much work [laughs]. I’m glad I’ve done it, but I look at it now and I’m like, ‘Oh my god.’ I basically have a blackout from writing it. I can’t even remember that time.

The Story of Art Without Men by Katy Hessel is published by Hutchinson Heinemann and is out now. The Story of Art as it’s Still Being Written, curated by Hessel, is also on show at Victoria Miro Gallery in London until October 1, 2022.