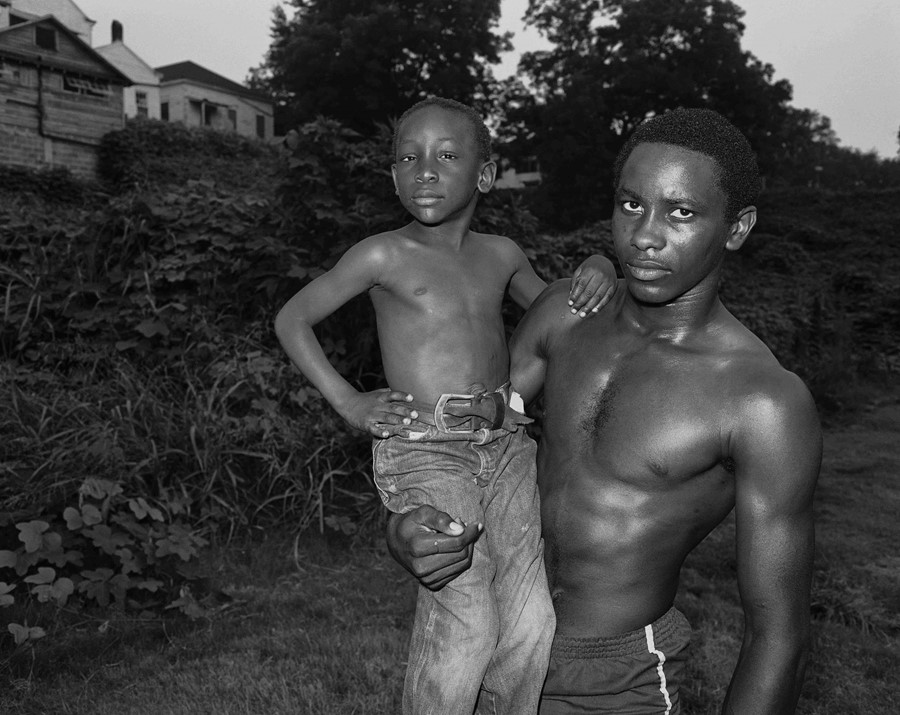

As a new exhibition of his work opens in New York, Baldwin Lee talks about capturing Black American life across the South in the 1980s – and why he eventually put the camera down

Baldwin Lee first encountered the American South in 1982, when he began a teaching job at the University of Tennessee. He didn’t know much so he drove, all the way down to Tallahassee and back up again. “I purposely stayed off the interstates as much as possible to get an understanding of what everyday life was like,” says Lee. The trip changed him for good; when it was done, he knew exactly what he needed to photograph.

When I ask Lee what drew him to the South and the Black Americans he photographed, Lee tells me he has to start from the beginning – his childhood. Born in Brooklyn and raised in New York’s Chinatown in the 1950s, he grew up in “an insular world, just like any small town in the South.” In Cambridge and New Haven – the former as an undergrad at MIT, the latter as a graduate at the Yale School of Art – Lee received an education that “wasn’t set forth in any curricula.” At both institutions, Lee experienced a new social order, “the particulars of white America.” There was the roommate who wore a smoking jacket and made martinis, last names that alluded to prominent families. “It was fascinating to me,” Lee remarks, “and also off-putting because I realised at that point I didn’t belong to any of this stuff. It wasn’t a systematic exclusion, but it was an exclusion based on non-interaction.”

While at Yale, Lee studied under Walker Evans. And much like Evans’s photographs, Lee’s are precise, with an eye for contrast and symmetry (particularly evident in his landscapes), and characterised by a profound sense of balance, clarity, and control. As with Evans’s seminal American Photographs, they feel like vital records, relics of not just particular moments in time but history itself, history mapped out on the faces and bodies of people – here, the violent history of the American South.

The trip, Lee tells me, “put everything into really sharp focus. It was no longer conceptual or ideological.” The South offered a “true” education, one that both stunned and troubled him. “The first thing that really affected me was how, if I approached an older Black person and began to speak, the person would adopt a lower hierarchical social stance relative to me. His whole bearing and demeanour would change. There [would] be a subtle dropping of the head and the glance would always be downwards. There was this kind of obsequiousness, which was triggered because I wasn’t Black. It put into real sharp focus what the history of enslavement and subjugation had wreaked on an entire population. It just really hit me straight in the gut.”

Lee’s process was deeply collaborative. He used a 4 x 5 viewfinder camera that had to be mounted on a tripod. “It obviates the possibility of surreptitious photography,” says Lee. “You have to ask somebody’s permission and you have to enter into a contract with the person that you want to photograph.” The first question people would ask when Lee approached them, he tells me, was “Why do you want to take a picture of me?” “There is no bullshit to answer that question,” says Lee. “You have to be able to say, with certainty and precision, exactly why. It’s a disarming question. When I am confronted with a question, I have to have an answer. It might have to do with a grace of stance, how somebody may be leaning against a car. It may have to do with the way that person may have been laughing or talking to friends. But it always starts with something extremely specific.”

For a time, Lee kept photographing. He took more trips and grew “fearless”. “I would approach anybody, anywhere, anytime, anyplace. Day or night, I would knock on doors.” The material seemed endless. “It had this draw to it. I was drawing buckets of water from a well that would never run dry. I just could not exhaust the subject.”

Eventually, Lee stopped taking photos entirely. Writing on attention, French philosopher Simone Weil warned that “the capacity to give one’s attention to a sufferer is a very rare and difficult thing; it is almost a miracle; it is a miracle.” In an interview with Jessica Bell Brown that accompanies the work, Lee says one of the reasons he quit is that he could “no longer reconcile the difference between the lives lived by the people I photographed with the life I lived.” There is merit in putting down the camera, of knowing when it’s time to leave; there are other ways of seeing, ones that evade capture.

Baldwin Lee is on show at Howard Greenberg Gallery in New York until 12 November 2022. An accompanying monograph, Baldwin Lee, will be published by Hunters Point Press in September.