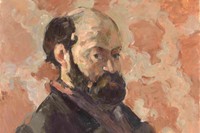

As a major show of Cezanne’s work opens at Tate Modern, seven contemporary artists reveal how the French painter’s work has inspired them over the years

In his 1922 book Since Cezanne, art critic Clive James states that “there is hardly one modern artist of importance to whom Cezanne is not father or grandfather, and that no other influence is comparable with his”. Exactly 100 years later, as a major, career-spanning exhibition of some 80 of Cezanne’s paintings opens at Tate Modern, it’s clear his impact remains.

Maybe it’s in his impulse to break with convention, how he used colour not only as shade but structure, his love of motifs or how his painting process was a means of organising sensations. Perhaps it was his resolute commitment – he made very little money from his work and yet he said he wanted to die painting. From essays and interviews, here seven artists reveal what Cezanne means to them.

Vanessa Jackson, British Painter

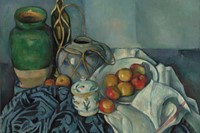

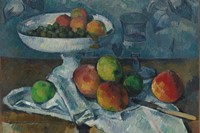

“I was first drawn towards Cezanne, particularly his still life paintings, as a teenager learning how to see the world in the everyday. He reappeared with greater significance through understanding the relationship between perception and making in the phenomenological writings of Maurice Merleau-Ponty in his poignant essay Cezanne’s Doubts. The ever-anxious Cezanne is portrayed with great sensitivity as he constantly tested his vision as an artist, drawing and painting the sensate experience of looking without the need of naming. Cezanne broke with the atmospheric Impressionist palette of complementary colour in search of chromatic nuances to put emphasis on the light emanated through the dark, optimising perspective with material substance. Chromatic sensation, with his superb use of blue, continually vibrates on the surface.

This extraordinary artist did not feel he had to choose between feeling and thought, with no distinction between ‘the senses’ and ‘the understanding’. In a lifetime committed to making, we can witness his comprehensive intelligence through the brilliance of his art.”

Gabriel Hartley, British Artist

“The Avenue at Chantilly at the National Gallery is the Cezanne that I have a most intimate relationship with; it is the one I return to on every visit, this and the Pierro Della Francesca Baptism of Christ. They are situated either side of the vast galleries, but in my mind, the two paintings – some 400 years apart – have become inextricably connected. Within both paintings everything feels linked, everything perfect.

“On my last visit while standing in front of Avenue at Chantilly it was the pocket of blue at the back of the receding arch that captured my attention. This deep blue, which wriggled itself to the foreground, forced a relooking at everything in the painting. A realisation that the blue sneaks its way into everything from the trees to the light ochre ground. A network of echoes. On each visit, I am surprised by different moments in this painting. Or maybe it’s more accurate to say I’m surprised by how differently I look at the painting, what I’m drawn to focus on, and the different associations I bring. Cezanne revels in this. The world changes, you change, and the painting seems to change, too.”

Phyllida Barlow, British Sculptor (Excerpt From The Exhibition Catalogue, Cezanne)

“I recall my first experience of looking at Cezanne’s Montagne Sainte-Victoire, when I was a student at Chelsea School of Art. It was 1961 and at the Tate Gallery, now Tate Britain, following a tutorial from Michael Andrews: ’line is a human invention – there are no lines in nature, or anywhere; go and look at Cezanne’s watercolor at the Tate, Montagne Sainte-Victoire, and look at how little there is – the economy of color, line, space, and where an empty space is in fact full.’

“And I have been back to look at Montagne Sainte-Victoire, each time a shock, comparable to listening to Beethoven’s Opus 133, or being caught in extreme weather – wind, rain, snow, things that disappear, where remembering fails the sentience of the experience.”

Kerry James Marshall, American Artist (Excerpt From The Exhibition Catalogue, Cezanne)

“I paint pictures too! I am driven by some of the same ambitions Cezanne expressed when he exclaimed his desire to ‘make of Impressionism an art that is solid and durable, like the art of the museums.’ No one looks to nature or the self anymore as the source of revelation in art, as Cezanne did. These days, artists don’t even learn to paint by copying other paintings. Examining pictures of paintings seems sufficient. “

Mary Ramsden, British Painter

“Cezanne dared to upend the status quo in an effort to get to the heart of what things feel like. Whether it be an apple, a piece of fabric or a tilted table he worked to manifest the essential characteristics of what was in front of him with a dogged belief in what paint can do.

“I love the very specific hard blue/black in his early works that can be both emphatic and tentative. And I experience a similar charge when looking at the zones of bare canvas in the later ‘unfinished’ works which feel withdrawn and brazen all at once. I find these beautifully handled contradictions so knock-out I can’t help but return to these images whenever I need a shot of courage.”

Luc Tuymans, Belgian Artist (Excerpt From The Exhibition Catalogue, Cezanne)

“My first encounter with the works of Paul Cezanne was with reproductions of his paintings in books. The first physical, real-time experience was years later in the Kunstmuseum Bern. Looking at them, I was immediately struck with an utter sense of austerity and unease, as if something was superimposed over the image to suppress and contain it. The work portrayed a lugubrious, dull sense of euphoria pursuing perfection within a narrow range. In other words, the encounter was a violent one.”

Peter Peri, British Artist

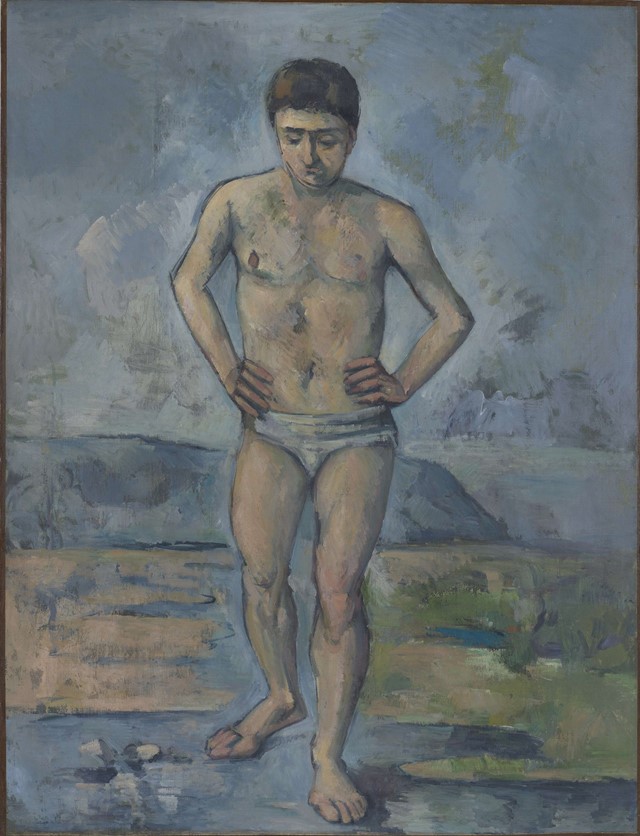

“I wrote my BA dissertation on Cézanne in 1994. As I recall, my student self was attracted to the dramatically deformed figures in his Bather paintings, also to descriptions of his personal heroism burdened by shyness.

“Visiting The Courtauld a few years later, I remember finding his Montagne Sainte-Victoire with Large Pine frustratingly impenetrable. It felt sterile and staid compared to the expressivity of the van Goghs nearby. I was about to move on when a Cezanne quote came back to me from my student research – something like ‘the shadow of the Montagne Saint-Victoire is convex, not concave’. I stayed looking, trying hard to find convexity. Gradually two distinct but co-existing renderings of space emerged from the painting’s myriad ambiguities. Everything seemed at its heart to be aimed at activating this dual life of the picture – concave and convex categories acting as entry points to its conception. I try now to always look at a Cezanne long enough for the magic duality to appear – it usually does, each time differently. My theory is that he considered a painting finished when it became animated in this way.

“Cezanne’s close attention to the changeover between one way of perceiving and another was much exploited by Cubism. However, his insistent focus on the infinitesimal moment of change itself – the threshold – does something unique. It seems to me that it puts us in direct contact with freedom.”

Cezanne will run from 5 October 2022 to 12 March 2023 at Tate Modern.