“There’s definitely a Frankensteinian element to my work process, cutting out the body parts,” says the American artist of her new London exhibition, Home Body

With rounded bouncy thighs, pointy elbows and splayed rubbery fingers, a woman in a lemon yellow slip dress, knee-high boots and a wide-brimmed hat sits on a turquoise chair that is only half solid. She is one of Harlem-born visual artist Tschabalala Self’s Black bodies: this time a bronze sculpture brightening the grey new-build backdrop of Coal Drops Yard in London’s St Pancras. The chair – with flimsy scribbled legs that defy perspective and a curved ironwork frame with unfinished lines that engulf its sitter – resembles more of a hasty sketch than a three-dimensional object. The body, too, follows the line of the hand: the twisted neckline on the dress, the impossibly pointed toes – yet it is fleshy and corporeal. Unlike the chair, the body is unmistakably solid.

At just under three metres tall, Seated is one of three parts included in Self’s London takeover ahead of this week’s Frieze fair – but it is also her first piece of public art. The sculpture’s Nickelodeon colour palette is purposefully engaging. “I had to mine my own practice for something to suit a large demographic in a space that’s not curated, especially in terms of its viewership,” says Self over coffee. “It had to be more neutral [intellectually], than some of my other works. It has two lives. So it can exist in someone’s periphery but if someone engages with it directly it has a higher, deeper meaning.”

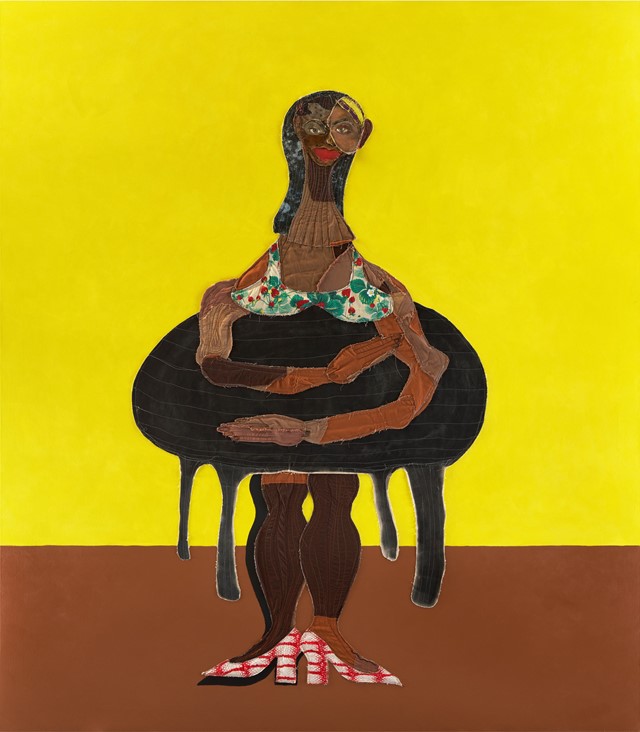

The chair – a ubiquitous prop used in portrait painting – is key to the work’s potential for deeper meaning, particularly in Home Body, her show at Pilar Corrias gallery, which has dedicated both its Eastcastle Street and Savile Row venues to showcasing Self’s work. While Eastcastle is dedicated to the artist’s appliqué paintings – the abstracted Black figures rendered in textile-scrap collage works, she’s best known for – Savile hosts her series of vibrant Leisure paintings. Where Seated could be seen as one of these latter paintings come-to-life, the same could be said of the Leisure series in reverse; they are 3D thoughts come-flat. In fact, they are everything come-flat. Cartoonish portraits of people merging with the chairs they are sitting on: a male figure in yellow (Leisure Man in Yellow Collared Shirt in Yellow Room) wears black, checked pants that are also the flat of the seat, the iron fretwork behind him bleeding through his yellow shirt. His legs are chair legs – two out of three of which wear shoes. The wall and floor are as flat as this man-chair, divided only by a scratchy black line.

Self’s figures become part of the furniture. It’s an expression she’d heard first in London. “I didn’t really know what it meant but I felt its meaning and I wanted to allude to that feeling – the idea of becoming embedded in the structure of your home,” says Self. “I like to linger on a word or a concept – approach it through a kind of formal expression, not something logical, [with] more of a poetic approach.”

With this playful, poetic simplicity, Self explores a plethora of social implications. What does a home symbolise? What is the role of the home in our collective consciousness? What does it mean to take a seat at the table, or to bring the domestic setting into the public sphere? “The home has two realities,” says Self. “An aspirational reality – a place of comfort, interiority and true self-expression. Then in reality it’s a place full of expectations, where people have to take on roles.” Here, the home operates as a set, a place where dynamics entangle – not unlike the brightly coloured, harlequin-patterned stage on which Self presented Sounding Board, an overblown comic domestic drama that debuted at Performa 2021 Biennial in New York City. (Sounding Board is now being exhibited as part of the Eastcastle Street show.) The cast and singers wore pieces from Self’s tie-dyed and patchwork-inspired collaboration with fuzzy footwear brand Ugg. “I like the idea of wearable art,” Self says of such collaborations.

Fashion plays a significant role in her applique paintings, too – their very construction being from scraps of discarded textiles, much of which was collected and kept by her mother, who was a dedicated seamstress in her spare time (she and Self’s father were both teachers in Harlem – Self’s four siblings have followed suit). At Eastcastle one can observe an entirely velvet woman (Red Room) – crushed, silvery black velvet all over, with a bralet embroidered from lurex silver and copper flowers; the kind you’d find on ruched party dresses for sale on a market stall. “I find her to be a mischievous character in the show, so there’s this idea that she’s slippery – silky and inviting,” says Self.

That interest in fashion emanates perhaps from her fascination with the body. In a recent interview, Self expressed her interest in plastic surgery – a career in another life. “It’s an interest in the body and how it can be rearranged,” says Self. She also acknowledges the way in which the body is read; the Black female body as icon as well as the idea of physically holding space. “I watch a lot of the American plastic surgery shows – they help me understand figuration and the body in 3D. It is anatomy geared towards aesthetics. As a figurative painter, it feels entirely within my remit. There’s definitely a Frankensteinian element to my work process, cutting out the body parts – or Pygmalion maybe.” Self’s extended limbs come to mind, hands askance of the body, too long and poking out at strange angles. Buttons on clothes are scribbles, as are the wrinkles of a wrist – each line wrought with a sewing machine. Under Self’s hand bodies become flattened, 3D again, and the inverse again and again. Planes merge and one begins to lose sight of which was first – the idea of the body or its actuality.

Home Body by Tschabalala Self is now showing at Pilar Corrias in London until 17 December 2022. Self’s sculpture is on show at the Kings Cross Estate until 31 January 2023.