Exhibiting seminal works from Japan’s Golden Age of photography, Michael Hoppen’s Frieze Masters booth provides a snapshot of one of the richest periods in the medium’s history

The emergence of a radically experimental and intensely collaborative group of Japanese photographers between 1957 and 1972 represents one of the most ground-breaking contributions to the art form in the 20th century. While the communal anguish at the cataclysmic events at Hiroshima and Nagasaki, compounded by the convulsive transformations Japanese society underwent during US occupation, galvanised artists in every medium, the fast and intuitive qualities of photography made it an especially expressive tool to capture the post-war experience of the nation.

“It was clear to me, when I first encountered their work, that I was looking at a completely new visual language,” says Michael Hoppen, whose eponymous gallery is showcasing seminal works by members of this iconic generation at London’s Frieze Masters. “This language broke all the rules, but there was a strong narrative thread running throughout. It was like listening to music. The more I listened, the more fluent I became. And through this fluency, I have been able to navigate my way around the various artists and estates over the years, so I am thrilled to be bringing these very special and rarely seen works to the table at Frieze Masters today.”

With this commercial context in mind, it is important to note that there was a small and limited market for photography in Japan in the 60s and 70s. Photographers therefore turned to the photo book as not only a means of circulating their work, but of translating the complexity of their ideas and emotions. While John Szarkowski’s landmark MoMA group exhibition New Japanese Photography launched Japanese photography on the international scene in 1974, there has been an increased number of solo retrospectives in recent years as the profile of individual Japanese photographers has risen. Although the importance of examining the personal legacies of these artists is thus indisputable, what Hoppen’s booth does most successfully is illustrate the web of relationships and influence that first animated their creative endeavours.

On the occasion of Hoppen’s presentation, we run down six essential post-war Japanese photographers you need to know.

Shо̄mei Tо̄matsu

Leading the line of photographers who became deeply concerned with the national trauma of the war – the way it scarred flesh and ruined cities – was Shо̄mei Tо̄matsu. He pioneered a revolutionary style of passionate subjectivity which was associated with VIVO, a short-lived yet influential collective that operated at the epicentre of Japanese photography in the 60s. Like most of his generation, Tо̄matsu was both fascinated and repulsed by the sleazy culture that sprang up around cities and military bases in Japan. With an unblinking, often jaundiced eye, Tо̄matsu photographed troops tossing sticks of gum and chocolate, raw strip club encounters and youthful rebellion. The chaotic ‘Coca-colonisation’ of Japan is conjured up by Hoppen’s selection, and no more symbolically freighted than in the 1959 display of a young girl blowing a bubble in the segregated ‘Harlem’ section of Yokosuka, a naval soldier eyeing up institutions of dank debauchery beneath gigantic, ill-shaped letters. As always with Tо̄matsu, we are never far from the impression of despair.

Kikuji Kawada

The influence of Tо̄matsu’s radically engaged form of photographic inquiry – particularly probing the conflicts within the Japanese post-war psyche – can be seen subsequently in the work of Kikuji Kawada, who is known almost exclusively for his iconic book Chizu (1965). Hailed as the ultimate photo book-as-object, it fetches astronomical prices at auction and is virtually impossible to catch sight of today. It is Kawada’s mental mapping of history, horror and memory, expressed through details of stains burnt into the walls of Hiroshima’s Atomic Bomb Dome as well as images related to the iconography of occupation. In the company of Kawada’s visions of a crumpled Lucky Strike cigarette packet and a trampled “rising sun” flag – both of which exert an undeniable moral power via Kawada’s acknowledgement of his own stakes in the act of seeing – is a hair-raising print from his follow-up series Los Caprichos (1968–81). Vexed by his country’s state of cultural illness and decline, Kawada drew a remarkable parallel between his Japan and Goya’s Spain, revealing the grim truths hiding in plain sight.

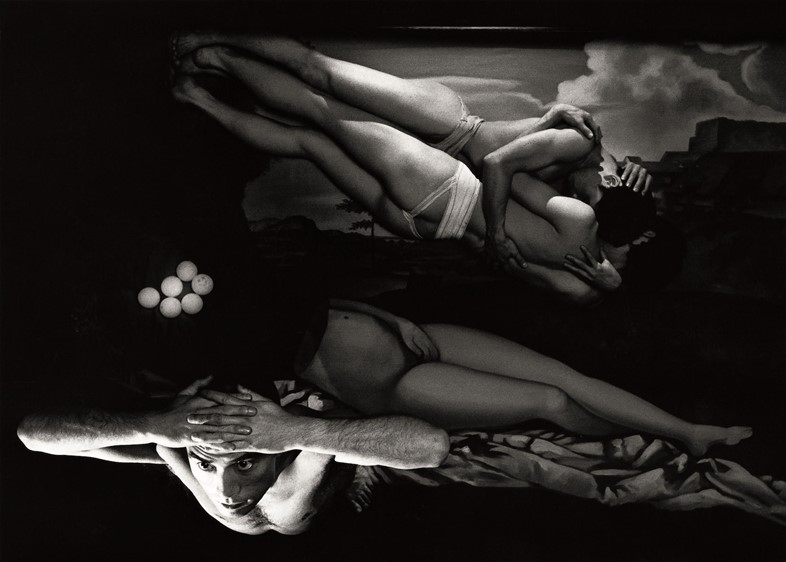

Eikoh Hosoe

A lively figure within Japan’s promiscuous avant-garde scene of the 60s, Eikoh Hosoe operated along an umbilical cord of radical creativity linking photography with performance at a time when the medium had yet to be fully assimilated within the fine arts in Japan. Pieces from two of his most legendary collaborations are on show here, testifying to the exciting ways he enlarged the field of photographic expression. In Ordeal of Roses (1961), Hosoe turned the famed writer Yukio Mishima into his muse, ensnared by his own contradictions throughout a series of menacing, Baroque-inflected tableaux. Equally astonishing is Kamaitachi (1969), which chronicles the rhapsodic rapport between Hosoe and ankoku butoh dancer Tatsumi Hijikata. A weasel-like apparition with two sickles for hands, Hijakata chases children, steals babies and tears through the fields of Akita, not far from where Hosoe had been evacuated as a child in 1944. The term ‘photographic theatre’ can thus be applied to Hosoe’s oeuvre as a whole: a stage in which time and space are manipulated to bring memories – and indeed nightmares – to life.

Daido Moriyama

One of the most storied legacies of the 60s is Provoke, a small press magazine that would go on to revolutionise photography inside and outside Japan. Playing a highly instrumental role in its development was Daido Moriyama, a nocturnal stalk-and-ambush hunter whose on-the-run grab shots came to epitomise the magazine’s are-bure-boke (“rough, blurred, out of focus”) aesthetics. Moriyama’s audacious exploration of new photographic terrain was shocking to photographic purists, but what is the point in having sharp pictures when you have fuzzy ideas? The graphically bold suite of prints Hoppen has staged evidence the gritty, darkened soul of Tokyo streets, a blend between decadence and eroticism. However, working beyond mere documentary veracity, what Moriyama has continually sought to capture is something invisible to the eye. After all, the grainy finish of these prints has its own charm, suggesting the sensation of coming into contact with another’s endless, inner world.

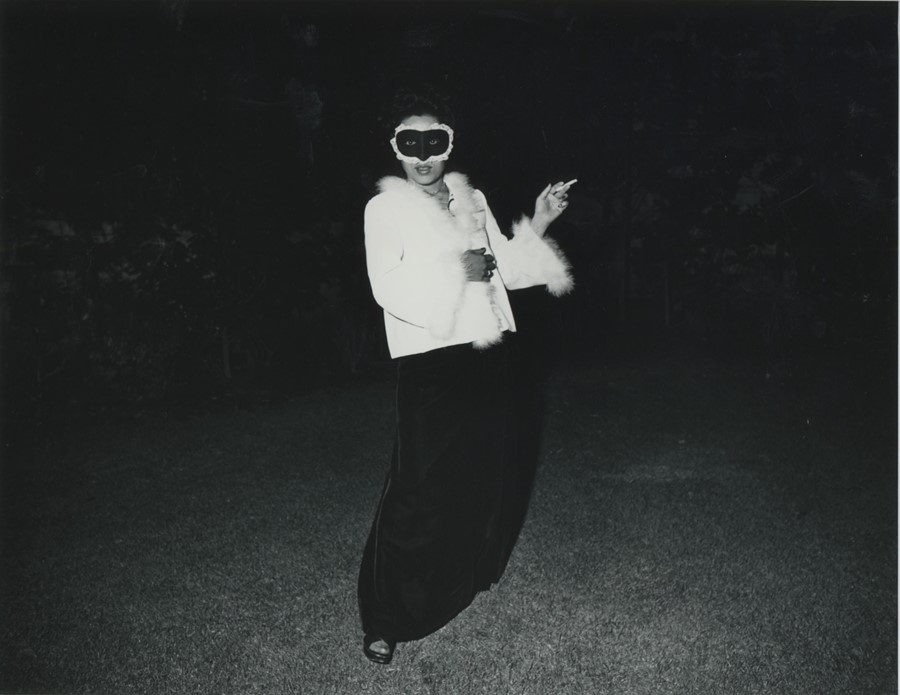

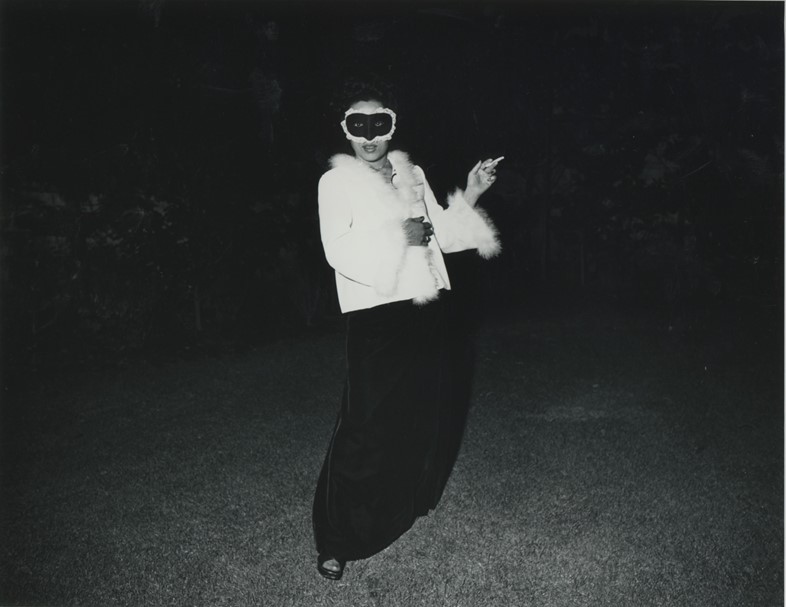

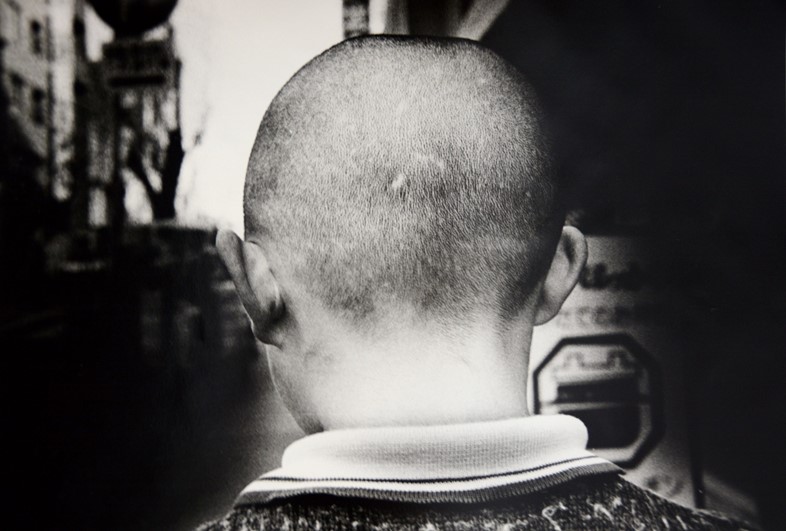

Keizo Kitajima

Another influential artist who incorporated Provoke’s are-bure-boke style and anti-commercialist ideals into their work, Keizo Kitajima rose to prominence in the 70s, when economic recovery and the increased accessibility of camera technology led to an explosion in the popularity of photography throughout Japan. It was with Moriyama – who dubbed him a “street killer in broad daylight” – that Kitajima set up CAMP gallery in the ramshackle Tokyo district of Shinjuku. For his legendary exhibition Photo Express (1979), Kitajima transcribed the “pop” cultural mecca that was Shinjuku – with all its pulsating, ecstatic energy and hedonistic values – converted the space into a darkroom to make wall-sized prints and produced instant booklets of his work. Much of this was incorporated into Photomail from Tokyo (1981), one of the most mythical books in the wide bibliography of Shinjuku nightlife. It is alas now very scarce, but the lone print in Hoppen’s booth – possessing an eye-watering contrast and febrile flamboyance – will knock you dead.

Masahisa Fukase

Last but certainly not least is Masahisa Fukase, who stands out as one of the most idiosyncratic and introspective photographers of his generation. As is the Japanese tradition, Fukase worked almost exclusively in series, making photo books such as Ravens (1986) and Family (1991) that have gone on to represent high points in the genre. While there is an opportunity here to purchase prints from these two legendary series, the surprise is the special display of two late series comprised of what are essentially proto-selfies. Towards the end of his working life, Fukase turned the lens on himself intensively, in Tokyo streets, bars and his own bathtub. These self-portraits – or “piles of tombstones” as he called them – were presented in an important show at Tokyo’s Nikon Salon in 1992, three months before Fukase suffered a fatal fall that would leave him with permanent brain damage. It was an absurd photographic funeral by an artist who, like none other, demonstrated how photography, irrespective of the subject, tends towards the fantasy of the self-portrait.

Michael Hoppen Gallery: Post-War Japan is on display at A08 at Frieze Masters until 16 October 2022.