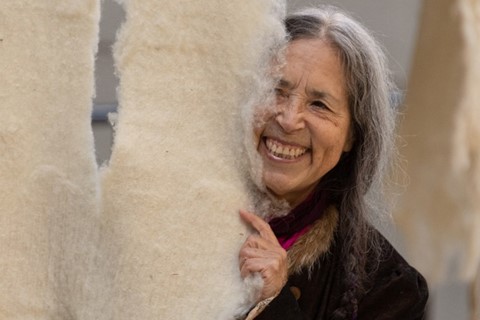

As the Chilean artist's 2022 sculpture and soundscape is installed in Tate Modern's Turbine Hall, we offer a five-point guide to the artist known for her ecofeminist, culturally rich works

Cecilia Vicuña’s global success has been a long-time coming, but now it’s here it shows no sign of slowing down. This spring she was a stand-out name in Venice’s eco-conscious 2022 Biennale and opened a sprawling survey show at New York’s Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum. As Frieze London kicks off this week, she has moved into Tate Modern’s cavernous Turbine Hall.

Born in 1948, the Chilean artist has been a pioneering voice on climate change, decolonisation and ecofeminism for decades. A poet, author, artist and activist, her work exists at the meeting point between art forms and means of communication. “My work dwells in the not yet, the future potential of the unformed, where sound, weaving, and language interact to create new meanings,” she says.

Brain Forest Quipu in Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall features two 27-metre-high fabric sculptures and a soundscape. The vast installations utilise Indigenous Amazonian craft techniques, foraged and found items. The Andean tradition of quipu used in the piece, a combination of knotting and weaving, was created as a complex system of communication. The work is “an act of mourning” to the destruction of forests, the inevitable impact this has on the climate, and the violence unleashed on Indigenous people.

1. She has been making art for half a century, but her profile soared to new heights in recent years

Cecilia Vicuña has been making work for five decades. She is widely considered to be ahead of her time on the political and cultural issues her work addresses, from feminism to the environment and social justice. For the last half a century she has expressed herself through writing, art making and street protest, publishing over 20 volumes of poetry. Global recognition of her radical, pioneering career exploded in the late-2010s with a recent major survey at the Guggenheim in New York and the reception of the Venice Biennale’s Golden Lion for Lifetime Achievement award earlier this year. “No one was interested in climate change then,” she has said of her three quieter exhibitions in New York between 1990 and 2002.

2. Her early work was made in exile from Augusto Pinochet’s CIA-supported military coup and dictatorship

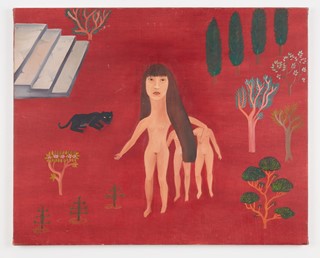

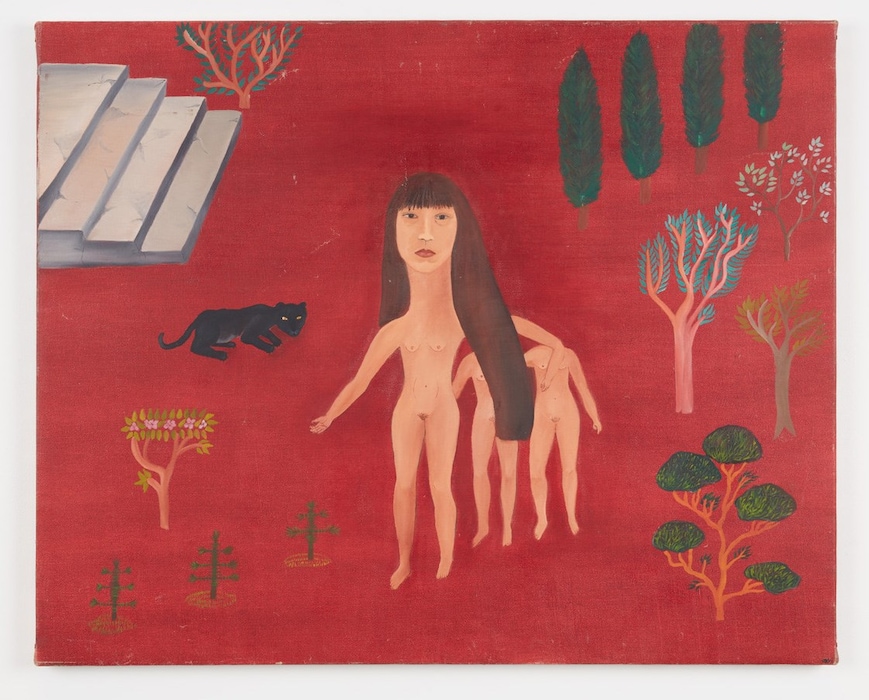

Vicuña went into exile in the 1970s, moving to London then New York during the former president of Chile’s violent dictatorship. This state of exile affected not just Vicuña’s works made during the dictatorship, but her career for many years after. Her ephemeral sculptures and installations capture feelings of transience and many are crafted from found items. In the 1970s she created multiple works inspired by the 16th-century paintings of Incan artists in Peru, who were forced to depict Catholic religious icons and convert to the religion under Spanish rule. Much of her work speaks to the evils of oppression and colonisation, not just within Chile but around the world.

3. She is often described as an ecofeminist and utilises Indigenous Amazonian techniques

Her works are aligned with ecofeminism due to the rich connections they make between nature and the lives of those who are oppressed. She draws on ancestral traditions and Indigenous techniques, using raw wool in her expansive material sculptures and knotting patterns from an ancient Andean system for recording statistics. In Quipu Womb (The Story of the Red Thread, Athens) from 2017, rich blood-red strips of unspun wool hang from the ceiling, with a rhythmic selection of knots down their lengths. The work brings together the textures of menstrual blood with the cycles of nature, inherently linking the plight of women and the world.

4. The influence of language is a long-running thread in her artwork, as well as her writing

A widely published poet and author, Vicuña explores the power of language within her art as well. Her popular painting Llaverito (Blue) from 2019 plays with words to powerful effect. The work depicts a playful crab-woman hybrid against a vibrant orange background, adorned with a set of keys. It references a derogatory Chilean term for women as “pestering crabs” and a Colombian phrase that describes women as the keyholders of all pleasure. “I decided to paint the liberated Blue Lady in her dual aspect as key holder and crab at once,” Vicuna says of the work. The crab-woman is neither idolised nor derided in this piece, she is allowed to be multi-faceted.

5. Many of her early works were not documented, “they existed only for the memories of a few citizens”

In 1966 Vicuña started her long-running series of “precarios”: fleeting sculptures which were exposed to the elements. Many of these were never documented. “They existed only for the memories of a few citizens,” says Vicuña. “History, as a fabric of inclusion and exclusion, did not embrace them.” These works inspired a new piece NAUfraga, created from ropes and other debris found around the sinking city of Venice. This work comments on the way humans have exploited Earth for material gain, dooming Venice and much more besides.

Cecilia Vicuña: Brain Forest Quipu is on display at Tate Modern’s Turbine Hall until 16 April 2023