The documentary photographer spent years capturing the unseen side of Marilyn Monroe. Here, her grandson Michael Arnold shares the real story behind the images

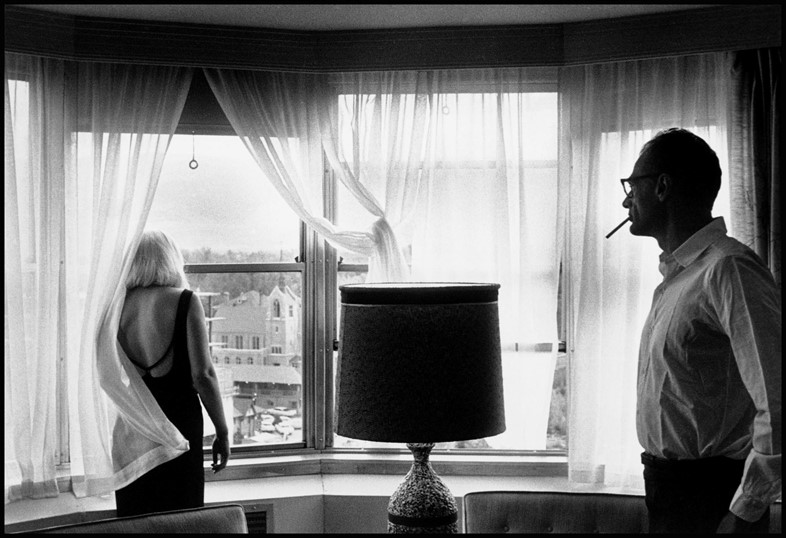

In 1961, not long after completing John Huston’s film, The Misfits, Marilyn Monroe was admitted to a psychiatric ward. In a state of acute exhaustion, the actress’ spiralling substance abuse amid the collapse of her marriage to playwright Arthur Miller (whose short story had been developed for the film) reached a climax.

One of the few photographers who captured Monroe in the months leading up to this crisis was Eve Arnold (1912–2012) – the first female member of Magnum Photographs and arguably one of the most successful photographers of the 20th century. Over a period of ten years, Arnold became a trusted confidant and companion. Unlike any other photographer, she would capture Monroe’s ascending fame, both in front of and behind the camera.

Little did Arnold know that The Misfits – shot in the Nevada desert – would be Monroe’s last motion picture. The following summer, the 36-year-old actress would be found dead in her Los Angeles home, in what many assumed to be a suicide by drug overdose. A pivotal event in Hollywood’s history, her turbulent life is captured in Andrew Dominik’s film Blonde, starring Ana de Armas.

“My most poignant memory of Marilyn is of how distressed, troubled and still radiant she looked when I arrived in Nevada,” Arnold recalled in her book Retrospect. “It occurred to me then that when she had lived with the fantasy of Marilyn that she had created, that fantasy had sustained her, but now the reality had caught up with her and she found it too much to bear.” Struggling with insomnia during filming, the actress’s worsening addiction to barbiturates and tranquilisers meant she would turn up to the set hours late. “She would take two pills and then two more pills and then forgetting, she’d wake up and be muzzy, and in the morning, she could hardly find her way around,” Arnold recalled.

In one striking photograph, currently on show at the group exhibition Hollywood at Berlin’s Museum of Photography, Monroe stands pensively – her solitary frame surrounded by the vast desert as she anxiously rehearses lines before a scene with Clark Gable. In a rare moment – in which Monroe is unaware of the camera – we see the real Norma Jean; battling with her demons and struggling to live up to expectations.

Arnold had first been introduced to Monroe at a party in 1954. The actress, who had admired Arnold’s candid photographs of Marlene Dietrich for Esquire in 1952, approached Arnold and said coyly: “If you could do that well with Marlene, imagine what you could do with me.” Shortly after, the professional collaboration between the two women commenced. It proved to be mutually beneficial – each intended to capture the transformative nature of fame as their celebrities reached new heights. “She had a naïve quality, but also a great sense of showmanship and self-promotion,” Arnold later recalled.

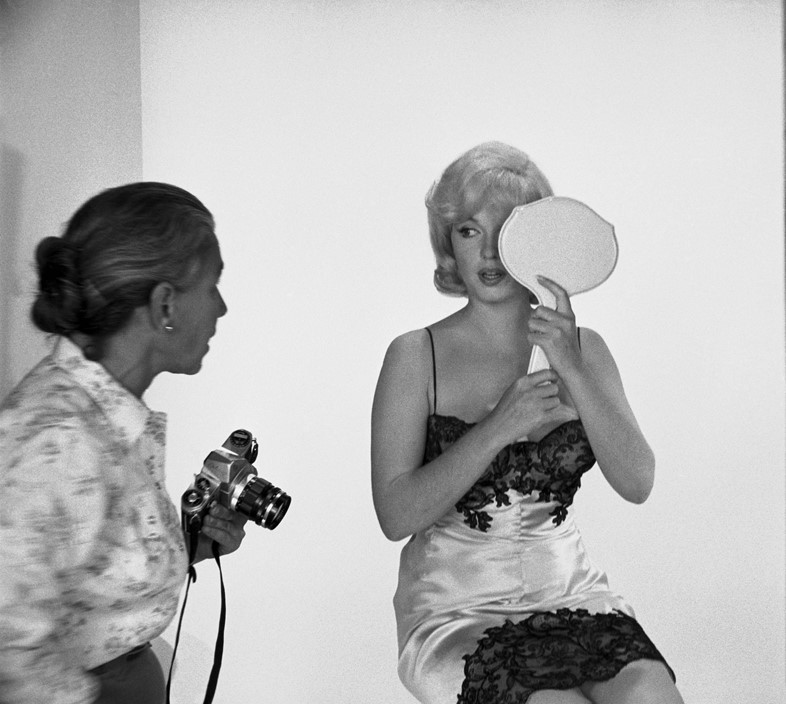

Through Arnold’s gaze, Monroe wanted to see a version of herself that was less staged, front-lit and retouched. “Hollywood at that time portrayed women in a very commoditised, sexualised and stylised way – instead of showing humanity, which is what Eve wanted to do,” Michael Arnold, Eve Arnold’s grandson tells AnOther.

Unlike other photographers (especially male ones), Arnold prioritised a compassionate approach, reflecting the real intimacy between the two women. As a female photographer in a male-dominated field, Eve knew how to play a role to thrive and gain access to certain people and places (perhaps even taking inspiration from Monroe). “She could be formidable and fierce and knew how to get what she wanted, but she could also be gentle and unassuming,” Michael says. She lived by her philosophy, that “if you are careful with people, they will offer you part of themselves. That is the big secret.”

Although Arnold’s career continually focused on women and overlapped with the Women’s Liberation Movement of the 1960s and 1970s, she resisted the ‘feminist’ label. “She was reluctant to even describe herself as a female photographer,” Michael says. “She found the need to distinguish male and female photographers quite artificial and frustrating, even though she certainly experienced some of the challenges of being one of the few women in her field.”

Regardless, it was undeniably Arnold’s celebration of and compassion for women – and her radical acceptance of being a woman herself – that led to her distinctive photographic gaze. Beyond the sparkling Hollywood mirage, Arnold helps us to remember the real Monroe today.