The photographer’s new book Bedfellows reflects on her own and other people’s experiences with men, spanning the full gamut of human emotion, from fear to euphoria

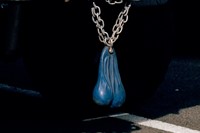

“I used to date a guy who impersonated me on the internet,” opens Bedfellow, the latest publication by New York-based photographer Caroline Tompkins. The book is a saccharine reflection of her own and other people’s experiences with men; sex and fear. There’s delicate images of couples embracing, the American landscape at its most tranquil and barren, other women in dignified poses and Tompkins herself in vulnerability. All this is paired with men doing what men do: men working on cars; men with their penises out, in different stages between throbbing and wilting.

The beauty of Tompkins’ work is in the subtleties, the nuances and the contradictions. This is something Tompkins is very aware of, she tells AnOther. “Women carry around contradictions – to love men is to fall prey to them. Even the physical act of sex can be complicated and violent.”

“You see me (the photographer) loving men, being afraid of men, and sometimes somewhere in between,” she continues. “When seen as a whole, the wholesome images look scary and the scary images look wholesome. These discrepancies also appear with the still lives and landscapes, which mimic these feelings between fear and euphoria.”

Tompkins grew up in Cincinnati, a small city on the Ohio River before settling in the metropolis of New York. Her work is a product of her surroundings, at once intimate, vulnerable and poetic. The sincerity also makes it something that could only be produced in America; the British wouldn’t have a hope. It is Americana and, in a way, is knocking about tonally with the men of the old guard – William Eggleston, Joel Meyerowitz, and Stephen Shore – while completely subverting it.

Here, in her own words, Tompkins tells AnOther how Bedfellow came to be, from her early influences to the life experiences that moulded her, and putting humour into tragedy:

“When I was in college, I photographed men who catcalled me on the street. I don’t really make work like this now, but I see the catcall pictures as the first seeds of Bedfellow. I was starting to think about power, danger, and gender, especially in the public space.

“When I got out of college, I felt a strong desire to make pictures about sex and particularly about my desire for men. At the time, I felt like I hadn’t seen much work that was purely about lust from a female perspective. All of the images of the ’female gaze’ were pink peaches and period stains, which always felt like what men thought women were interested in.

“As I started to make these sex pictures, a lot of them were a lot scarier than I had intended, and [I felt] that images that were purely sexual felt alienating. At this point, I had had a lot of scary relationships with men, and I started to realise this was the other side of the coin for most women. We desire men, but we must always fear them.

“I don’t know that I would have made this work if I didn’t get a restraining order from one man and get revenge porn’d by another. All the while, I still desired both of those men. I want the work to complicate this experience, like holding two truths at one time.

“I always tell people to make work about the things that keep you up at night. For me, that’s sex and danger. I listen to sex advice podcasts. I buy books about the erotic mind. I wonder why I put keys between my fingers when I’m walking alone. I fantasise about men. I watch TV shows about couples in therapy. I pay for porn. I get called a slut on the street by a stranger. I’m obsessed. How could I make work about anything else?

“For a while, I used to collect amateur gay porn. I used it as a reference for images I wanted to make. When I’d go to recreate these images, they always looked homoerotic, even though I was a woman photographing them. I realised that it was because of a few things. First, objectification is owned by men. Second, and more importantly, that those homoerotic images aren’t taking the danger women experience into account. When I see an oiled-up, muscly man, there is a part of me that finds it attractive, but an equal part that feels weary. Like, maybe this person is on steroids and is emotionally chaotic.

“I wanted to make sure there was some reprieve. It’s not all doom and gloom. If you talk about the danger too much, it alienates the women who enjoy sex. If you talk about the sex too much, it alienates the women who have experienced any kind of sexual trauma or fear. If you include humour, it allows everyone in. A lot of the things I’m describing in the writing are quite tragic, and tragedy alone isn’t very interesting to read about. If you put a joke in there, people might actually remember what you were going on about.”

Bedfellow by Caroline Tompkins launches on October 27 at 1014 Gallery in London with an opening reception from 6.30-9pm. The exhibition continues from October 28 to November 25.