As Leah Gordon’s extraordinary Kanaval series goes on show in Miami, the British photographer talks about colonialism, racism, and carnival as a space for creativity, catharsis and community

For centuries, the Taino-Arawakan people and the Carib Indians lived on the island of Ayiti (“land of high mountains”) in the tranquil blue waters of the Caribbean. All of that changed when Christopher Columbus arrived on 4 December 1492, charging in alongside the four horsemen of the Apocalypse. The Conquistadors brought colonisation, slavery, and disease to the once idyllic land, wiping out the indigenous communities and repopulating the island with people stolen from Africa.

Spain wasn’t the only European nation taking what was not rightfully theirs. By 1697, the French made inroads, forcing the Spanish to cede the western third of the island to France. After a century of brutal rule, the people overthrew this barbaric regime in 1804 to become the first Black republic on earth and the only nation to arise from a successful slave revolt. Suffice to say, Western powers were terrified by this ferocious show of force. Fearing retribution, they marshalled their resources to destroy the young nation, which took the name Haiti in tribute to its pre-Colombian roots.

In 1825, France ordered Haiti to pay reparations (worth £200 billion today) for the loss of income made off the free labour of slaves, a debt that wasn’t settled until 1947. Then, in 1915, the United States invaded the tiny nation, took control of the banks, and established a return to slavery through forced labour. After two decades of brutish occupation, the foreign invaders were finally ousted from the land, though that wouldn’t stop them from continuing to meddle in Haitian affairs.

Today, Haiti is the poorest country in the Western hemisphere, and ranks 68th on the UNDP Human Poverty Index sale, with an estimated 65 per cent of the people living below the poverty line, earning less than £2.04 per day.

For centuries, the Haitian people have borne witness to acts of savagery and wickedness so cruel, they introduced the archetype of the zombie – modelled on the enslaved – to the world. And yet, they lived to tell the tale, preserving their history and culture in carnival. The annual masquerade is a magnificent celebration of a people who have survived against all odds, honouring their ancestors and passing their stories along from one generation to the next.

Every element of carnival – the music, dance, costumes, and masks – speaks of a significant chapter of Haiti’s history. The troupes craft their own performative styles, creating a kaleidoscopic tapestry of arts, culture, and community that transform the road into a spiritual experience. In all things, Vodou is present. Though it has been intentionally maligned and misrepresented by the West as a political strategy to add insult to injury, Vodou is the lifeblood of Haiti.

“Vodou was both the inspiration and precipitation of the long fight for Haiti’s independence,” says British photographer, filmmaker, curator, and writer Leah Gordon, who first began travelling to Haiti in 1991. Gordon recounts the legendary ceremony at Bwa Kayiman on 23 August 1791, when a Vodou priest named Boukman sacrificed a black pig for the African ancestors, and in its blood wrote the words “liberty or death”. Slaves and maroons gathered from far and wide to bear witness to this historic event, and returned to their plantations and outposts to spread the message of rebellion.

“After the Haiti Revolution, the formerly enslaved peasants had three tools for their ‘counter-plantation’ position: the Kreyòl language, the Lakou system and the belief-system and ritual practices of Vodou, a triumvirate of linguistic, territorial and cultural resistance,” says Gordon, who honours these forms in the new exhibition Kanaval at MOCA North Miami (this is accompanied by a book of the same name from Here Press, and a spellbinding documentary film, Kanaval: A People’s History of Haiti in Six Chapters, which she directed with Eddie Hutton Mills).

Gordon recalls arriving in Haiti at a time when “the local politics felt quite radical and hopeful.” Inspired, she began working on Kanaval in 1995, travelling to the Southern port town of Jacmel over a period of seven years to chronicle its unique expression of Carnival, which goes back 200 years to the independence of the island itself.

Working with a 60-year-old Rolleicord medium format twin lens reflex camera and a Lunasix light meter and shooting black and white film, Gordon wanders the streets searching for people who agree to be photographed. Understanding not only the importance of consent, but of establishing a genuine connection, Gordon speaks Kreyòl. The photography process is slow, which allows her to transform and create: “a space between myself and the sitter is created, which seems to leave the street and enter the territory of the old-fashioned portrait studio.”

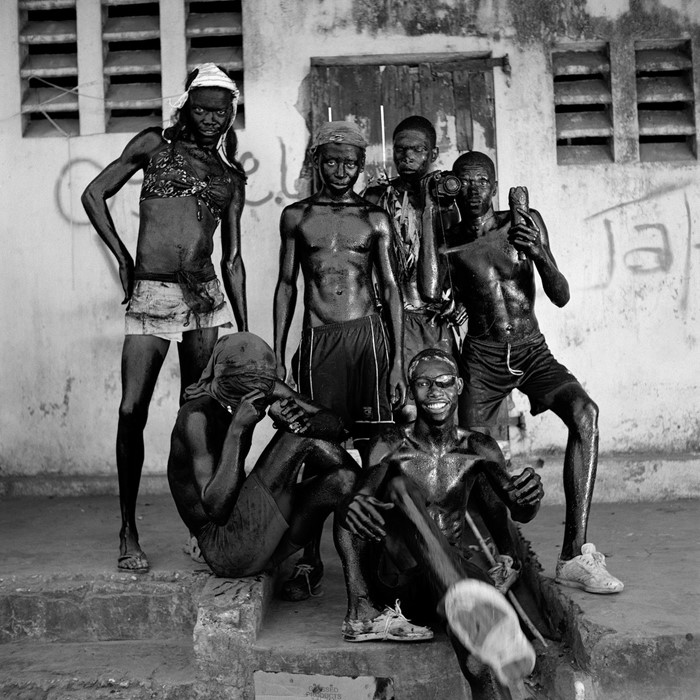

Gordon’s sitters never break character, striking poses that convey the story and spirit of their masked characters in what one of the essayist in her book refers to as “performed ethnography.” The result is a singular collection of mythic figures that convey the hypnotic energy of carnival – such as “the Zel Maturin, satin clad devils in papier maché masks with four foot hinged wooden wings which they smack together dangerously and the Lanset Kòd, hordes of behorned, shirtless men, skin shining with an oily patina of cane spirit, syrup and charcoal, who rage the streets, ropes in hand, before diving communally into the ocean at the end of the day.”

By making photographs, Gordon found a space for herself within carnival, but she also recognised the potential damage images taken out of context could do. “As a photographer, I have always been keenly aware of the difficulties and responsibilities in representing Haiti,” she says. “Since the [revolution], Haiti has been a mythological epicentre for racist and colonial anxieties and many of these encoded mythologies are reproduced and replicated through the visual representation of Haiti.”

Recognising that her early photograph of the Lanse Kod (Lanceurs de Corde – Rope Throwers) could be used to reinforce negative stereotypes, Gordon began to search for new strategies of “damage limitation.” Realising the images alone were not enough, she returned to Jacmel three times during calmer periods outside carnival. She began collecting oral histories from troupe leaders to tell the stories behind the masquerade to reduce the spectacle and restore the narrative to the photographs.

Driven by a love for folk traditions and histories, Gordon takes exquisite care to preserve the voice of the people in her work. When asked about the ways in which carnival is a space for creativity, catharsis, and community, Gordon steps out of the way and lets the people of Haiti, who are narrators in the film, explain. “I think we carry Haitian history in all of our bodies and this history manifests in everything we do … in our song, dance, religion and especially through our carnival,” says Madame Raymond of the troupe Trese Riban.

Lauture Joseph Joissaint of Chal Oska – a troupe that draws attention to the political abuses of the past – points to carnival as a time for devotion, enjoyment, and release; something that Haitian artist Andre Eugene understands perfectly. “In this country we have a lot of misery but we have a lot of joy too” he says. “Sometimes I think without carnival people would go mad.”

Leah Gordon: Kanaval is on show at the Museum of Contemporary Art in North Miami until 16 April 2023.