The Orange Line tenderly documents the predominantly Black, working-class community that lived along Boston’s Orange Line subway system in the 1980s before it was demolished

If you were to visit the patch of Boston captured in Jack Lueders-Booth’s book The Orange Line today, you would find a very different scene to the one depicted in his photos, which were shot nearly 40 years ago. “The area today is as predicted: up-scaled modern buildings, high-end retail boutiques and fine restaurants,” the Boston-born photographer tells AnOther. Once home to a predominantly Black working-class community, the worn-down southern stretch of the city’s Orange Line subway system was on the precipice of change when Lueders-Booth arrived to photograph the neighbourhood back in 1985. The loud, clattering railway, along which many people lived and worked, was scheduled to be demolished and rerouted, and fears of rising rents and displacement hung in the air. Shot over the course of one year, Booth’s warm yet unflinching book captures this precarious moment in time from the perspective of its residents – serving as a record of the people, families and workers who lived there before gentrification took hold.

A celebrated photographer and three-decade Harvard University lecturer – where he taught between 1970-1999 – Lueders-Booth’s interest in photography began at a young age. While most image-makers fall in love with the act of taking a picture, it was the alchemy of the dark room that first sparked Lueders-Booth’s curiosity, after watching his “serious amateur” father develop photos shot on an Exakta camera in the bathroom of their family home. “It was not until I was in my early twenties that I attempted to learn enough to do it,” he recalls. “To observe an image appear, slowly and mysteriously, was magic – and a magic that encouraged repetition. That was it. From 1965 until now, photography has been a way of life for me.”

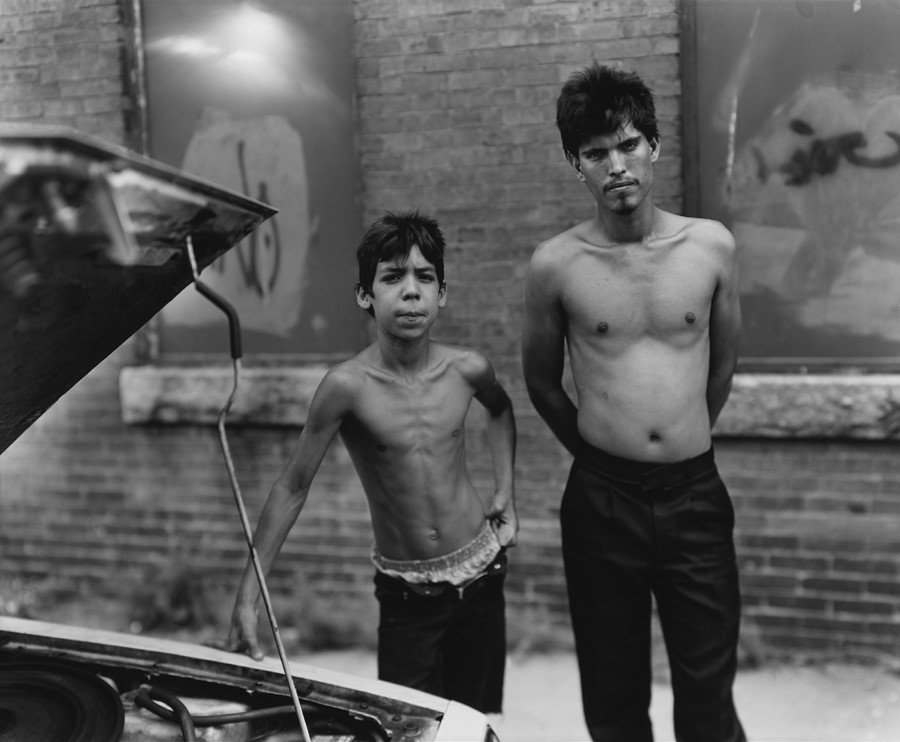

What Lueders-Booth describes as a “pathological” obsession with image-making has taken him into the heart of several fringe communities over the decades, photographing women prisoners, chronically ill people, motorcycle crews, and families living on the dumps of Tijuana. Now 87 years old, the photographer delved into his archives to produce The Orange Line with publisher Stanley/Barker following a recent exhibition at Gallery Kayafas in Boston. Featuring tender, black-and-white portraits shot on the street and inside people’s homes, the series is a particularly powerful example of Lueders-Booth’s lifelong admiration for the outsider.

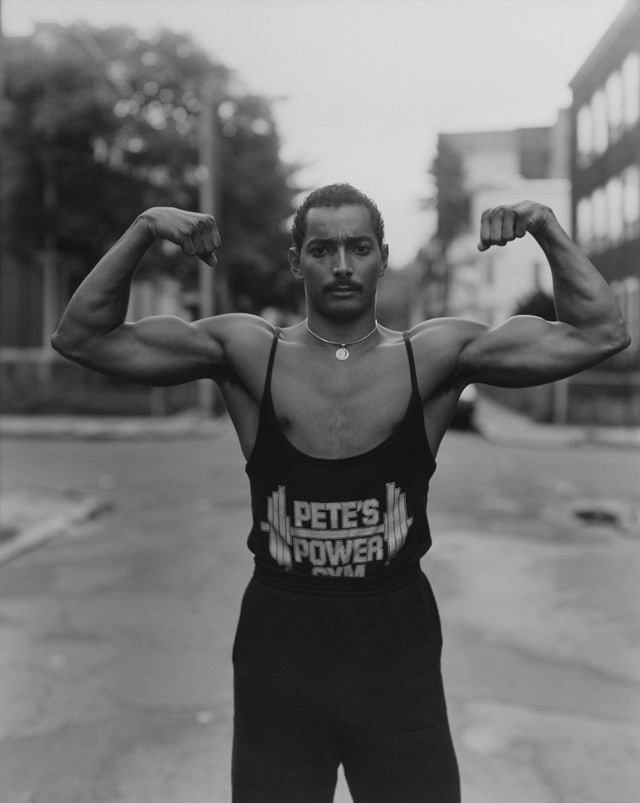

This care is felt in his vivid descriptions of the characters in the book, such as the beautiful bodybuilder who appears on its cover: “I was immediately struck by his fit appearance, his Gold’s Gym tank top, and most interestingly, something special about his presence that I had to get on film. Placing the setting sun behind him gave a rim-lit emphasis to his muscular biceps and a softness to his face. It was an accurate depiction of the dichotomy [of his look].” Another resident Lueders-Booth remembers fondly is a woman called Mrs Ball, who seems to represent the altruistic heart of a community hit by socioeconomic hardships. “Mrs Ball was, in all ways, a saint,” he says. “She invited me to her home to take photographs of her and the many children that she foster-cared. There were perhaps eight, all of whom matured to full adoption.”

As a whole, what makes Lueders-Booth’s photography so compelling is that he doesn’t try to portray his subjects in a certain way. Rather, he allows them to take total control of the moment: “I neither direct nor coach those who I photograph. I say next to nothing, letting them choose what of themselves they wish to reveal. My conceit is that I can sometimes recognise authenticity, and my goal is to be a faithful witness to it.”

The Orange Line by Jack Lueders-Booth is published by Stanley/Barker and is out now.