Matters of life, death, love, the body and the soul are all present in George Rouy’s startling new exhibition at Almine Rech in Paris. Here, the British artist talks about how he first fell in love with art, and why his paintings must “vibrate”

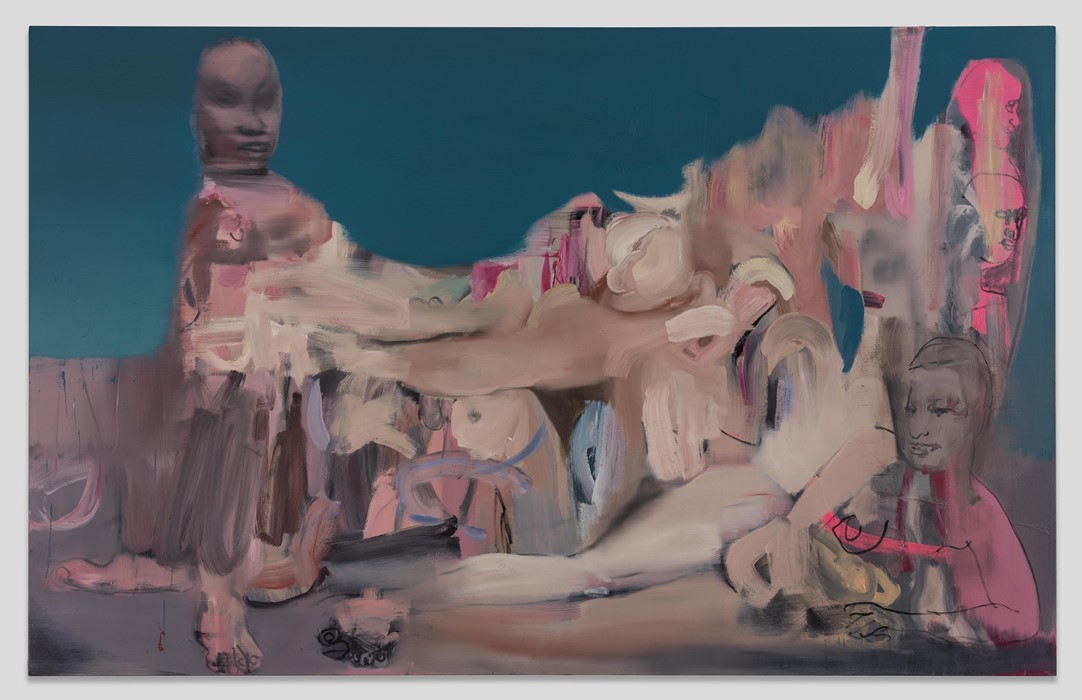

George Rouy’s work, usually bursting with carnal desire and vitality, takes a different tack in the final painting featured in his new solo show in Paris. In Stars Beneath my Feet, a ghostly figure melds into an abstract landscape, succumbing – or suffocating – underneath vigorous swathes of coloured paint, while a pink haze – a soul, an aura – drifts skyward. “This is the closest to a death painting I’ve ever made,” Rouy explains. “It’s probably the heaviest painting [in the show], maybe the most challenging. But I think the whole show is challenging ... it’s a bit full on.”

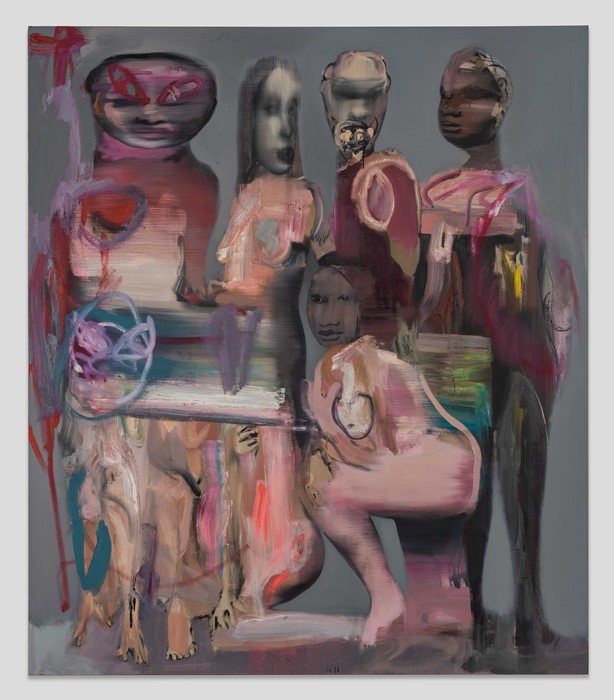

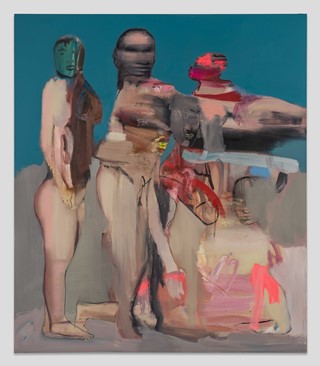

Belly Ache at Almine Rech is Rouy’s first ever solo show in Paris, and gathers together over ten paintings and one sculpture – similar to the one pictured in the artist’s portrait – which he made during the past year. Matters of life, death, love, the body and the soul are all distilled onto his frenetic canvases via lurid colours, Richter-esque blurs and orgy-like tableaux. In person the day before the show’s opening, Rouy is almost as colourful as his paintings, his hair dyed turquoise to match his eyes, and his mouth a metallic blur of gold grills.

Originally born in Kent – he now splits his time between the quaint British county and Paris – Rouy’s route to becoming an artist is a familiar tale. Preferring drawing over academia as a child, he was supported by an art teacher in secondary school and perhaps more surprisingly, his parents, who he says are staunchly “pro-art” (Rouy’s siblings, Elsa and Alife, are artists too). He remembers a life-affirming trip to the Saatchi Gallery in London with his father when he was nine years old. “I fucking fell in love with art. It felt like you were in a bloody funfair rather than the art exhibition,” he says, citing the “wild” work of the Chapman brothers, Chris Ofili and Damien Hirst. “I fell in love with the experience ... it was so strange. That was an amazing time for British art.”

After graduating from Camberwell College of Arts in London in 2015, Rouy attracted an art-world following for his vast, spectral paintings of nude, balloon-like figures in pink and red, which were haunting in their otherworldliness. In 2021, however, his art underwent a seismic stylistic shift. After seeing a series of unsettling dance pieces by choreographer Sharon Eyal, Rouy swapped his spongy style for work that flirted between figuration and abstraction, favouring chalkier colours which became more and more garish as time went on. “When I saw Sharon’s pieces, it was a concentrated experience that really hit me hard,” Rouy told me earlier this year. “It was like the ultimate form of what I wanted to achieve or what I loved about art … it was all about an intuitive response, an emotional thing, not intellectual.”

The same can be said about the paintings in Belly Ache, which are guided by feeling above all else. “A lot of the works are very personal, but they’re also not at the same time,” says Rouy. “I think it’s important that they’re not autobiographical. There needs to be enough space so that the viewer can enter it and not just assess it as these stories, because they’re not stories. They’re almost like symbols.”

The figures in his paintings are mostly lifted from found imagery, with the body as a central concern; like Francis Bacon, Rouy often “signposts” bodily anatomy, lifting out jaws, hearts and genitalia in graphic, cartoonish strokes. “I really enjoy this one,” says Rouy of Fire in the Head, a milky painting of four figures clutching at one another, “because it’s got tension, it’s got romance, it’s got a bit of violence. And a screaming head.”

Music is also an integral part of the artist’s practice; he begins his mornings in the studio listening to techno to stay awake, and then progresses to pop and punk. “I love every type of music,” he says. “I find it very hard even walking down the street without music. I get quite sensitive and overwhelmed just walking, so music focuses me – especially when you’re painting.” His love of music is clear in the work, which seems almost to operate at a higher frequency, shimmering and rhapsodic. Of his paintings, he says he is “always thinking about the energy. It all needs to kind of vibrate.”

Has moving to Paris changed the way Rouy works? “I can breathe a lot more in terms of my practice,” he explains, citing the food, the drink and the late night bars on offer in Paris as a welcome respite from painting. Plus, Faked Real, a gargantuan painting of a reclining nude that features every shade of pink under the sun, references Édouard Manet’s sensual Olympia, which hangs nearby in the Musée d’Orsay. “It’s hard sometimes, because you’re making paintings but at the same time you love looking at paintings, so there’s always influences, but it all comes out in a very natural way,” says Rouy of the art historical links to be made between his work and that of others. “That’s the beauty of it. That’s the beauty of life. Hopefully, my paintings stand up in relation to everything else as a certain unique experience. Hopefully, they have a presence. I just love painting.”

Belly Ache by George Rouy is on show at Almine Rech in Paris until December 22.