The artist’s new exhibition at Yorkshire Sculpture Park considers questions of power and ownership, colonialism and free speech. Here, in her own words, she talks about her “critical” new murals

To stumble upon one of Lakwena Maciver’s kaleidoscopic murals is to confront a kind of spiritual affirmation. “Naturally, I’m a bit of a pessimist,” she admits on a Zoom call. “That’s why the work is so positive. I’m trying to remind myself that there’s hope, because real life is tough, isn’t it?” For the last ten or so years, Maciver has also reminded everyone else that there’s hope, too, often forgoing the gallery system to redeem London’s grayscale dreariness with a series of technicolour prayers celebrating black life, Black joy, and Black power. Those phrases – “NOTHING CAN SEPARATE US,” “THE BEST IS STILL TO COME” – ring with optimistic certainty; it’s fitting that Maciver’s name translates, from the Acholi language of northern Uganda, to “messenger of the chief.”

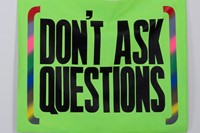

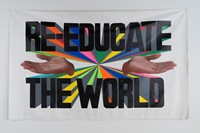

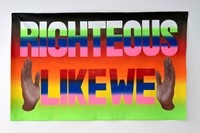

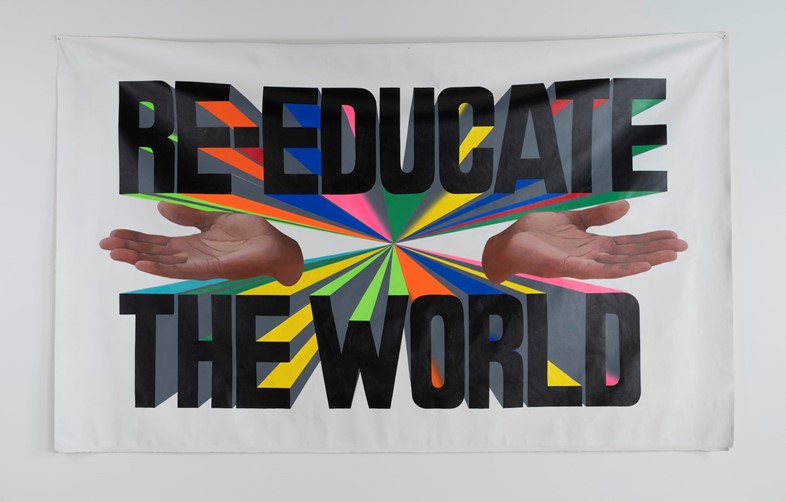

But the artist’s latest exhibition at Yorkshire Sculpture Park, A green and pleasant land (HA-HA), suggests a departure from her usual positive meditations. It’s more critical than her previous work, with messages that read more like indictments or demands than hopeful reminders. “It’s addressing how the quest for utopia can end up restricting the freedom of others,” she explains.

In the 18th century, the UK’s landed gentry began appropriating communal land and fencing it off from the common people, who had previously used it to grow crops and make a living. And to keep livestock off the newly-privatised land without spoiling the pleasant view, sunken fences called ha-has were dug into concealed ditches surrounding the land, creating the illusion of openness. As a result, half of all land in England is now owned by less than 1% of the population.

In her new exhibition, Maciver uses the ha-ha as a metaphor to consider questions of power and ownership, colonialism and free speech, and how, beneath the great illusion of our vast cultural openness, public speech and space are still increasingly and tightly controlled by a privileged elite.

“I grew up in Enfield, north London, but my family moved to Ethiopia for two years when I was six while my dad was working for the United Nations. It was like a golden era in my family – a little glimpse of paradise. A lot changed for me. My dad is Ugandan and my mom is English, but I sort of looked Ethiopian back then, and after growing up as a minority in London, suddenly everyone around me looked like me. I don’t know that I necessarily belonged, but I could at least blend in, and I’d never had that before. Plus it was sunny all the time, it was warm. The country was colourful down to the handmade street signs, which had an effect on me that I didn’t realise until later. Growing up, my dad was unemployed a lot of the time, so our family had a complicated relationship with money. But in Ethiopia, my life was so pleasant. In the eyes of a child, everything was perfect: my dad had a job, the country was beautiful. And I was happy.

“But then we came back to London, and my first memories of being back are of the cold, and the grey sky – and I was a minority again. It was a big shock for me; we thought we were going to return to Ethiopia at some point, but then it didn’t happen, and so there was a lot of pain and heartbreak about that for a long time. It was a defining moment for me. I had this sense of upheaval, like I had been picked up and locked in this alien place where you can go a month without seeing the sun. I struggled to process that. And I think my work has been a way for me to combat this greyness and all its associations, to bring an antidote to it.

“My journey kind of started in Brazil, where I was living for six months after I completed my A Levels. I was studying modern languages at King’s College, and was there learning Portuguese, staying with some friends. There was this guy there who invited me to paint a mural on this huge wall inside a church, which ended up changing my life. I picked out this Bible verse, which said: ‘You’ve turned my wailing into dancing, You’ve taken away my clothes of sadness and clothed me with joy.’ And I painted all these colourful patterns around it. But it wasn’t that planned out, it was instinctive. That was when I realised that, when left to my own devices, that was the kind of thing I would do. So when I got back to London, I switched to graphic design.

“I Remember Paradise was a really key painting for me. A couple of years after I graduated from King’s, this gallerist in LA who was following my work asked me to do a mural at this street art festival in Miami. I was so scared. It was my first big mural, and it was something like 130 feet long. In a way, I think it coined what the work is all about for me, because it still resonates almost ten years later. I was discovering Barbara Kruger, Roland Barthes, and Jean Baudrillard at the time, and that mural felt so connected to the early graffiti movement in 1970s/1980s New York, when these kids were reclaiming public space. I’ve always found that to be exciting.

“Painting in public spaces, which is where a lot of my work appears, feels connected with humanity in a way that the privacy of your studio doesn’t. People engage with it more, they walk alongside it, they live with it. It’s social. And so it connects me to the world. Someone like Emory Douglas – the former minister of culture for the Black Panthers – is one of my heroes, because the graphic design he created was directly about connecting with people, and because the images he made circulated in the newspaper the community was reading, they connected more directly with people than paintings hanging in a gallery do, or images hanging on the walls in a wealthy person’s home. Projecting words into public spaces is like intervening in the public conversation.

“I’ve always been interested in the power of words, what they mean, how they look. I used to paint signs for protest marches I would go to with my mum, and we were very much into music as a family too. Someone in the house was always singing. My mum’s mum was an opera singer, and my dad led a boys’ choir in his village when he was a child. My sister is a musician too; she used to sing in a choir that did a lot of church events in community halls. So music and gospel are at the heart of what I do, and this idea of paradise is so connected to that. I believe there’s a lot more going on than what the eye can see, and in a way, I’m trying to paint what’s not being seen. What’s in front of me perhaps depresses me, and so I’m trying to catch a glimpse of something that doesn’t.

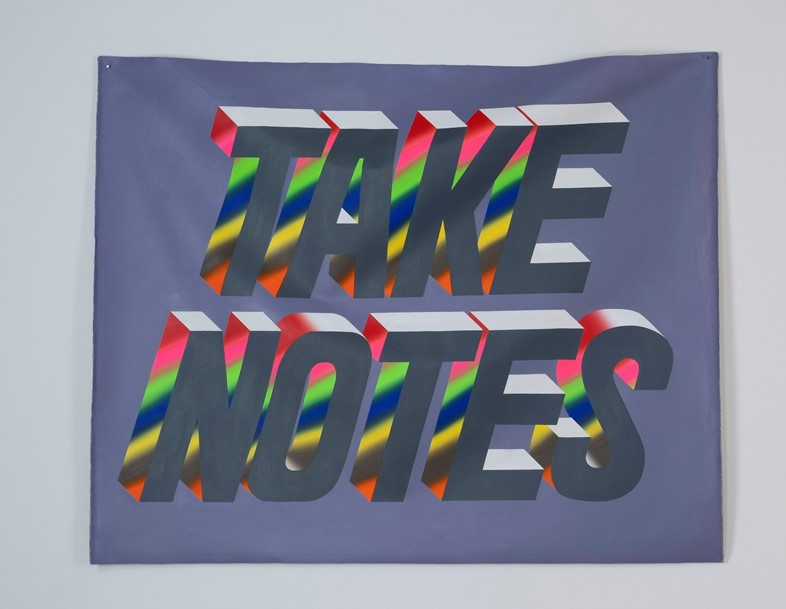

“These new paintings and textile works I’ve made for my show at Yorkshire Sculpture Park are a lot more critical than my work has been in the past. It’s new ground for me, and are perhaps the most challenging works that I’ve made. The work takes its cue from the landscape at the park, which features a ha-ha – a discreet sunken fence dug into the ground, which was used by private landowners to keep animals out of their gardens without disrupting their views. I use the ha-ha as a metaphor for the boundaries which exist within public discourse, despite the illusion of openness. The work is a challenge to ask ourselves, particularly as culture-makers, to what extent we have replaced one orthodoxy with another, and to what extent public speech could be considered colonised.

“I will continue to long for paradise, but for now, let this work be a suggestion that we might not be as free as we appear to be, and that even if at this moment we happen to be on the right side of the boundary lines, they may well move, and we may find ourselves on the wrong side of them, stuck in a ditch.”

Lakwena Maciver: A green and pleasant land (HA-HA) is on at Yorkshire Sculpture Park until 19 March 2023.