Pieter Hugo’s new Johannesburg exhibition brings together portraits made over the past two decades that capture the “genetics, history, love and trauma” of his sitters

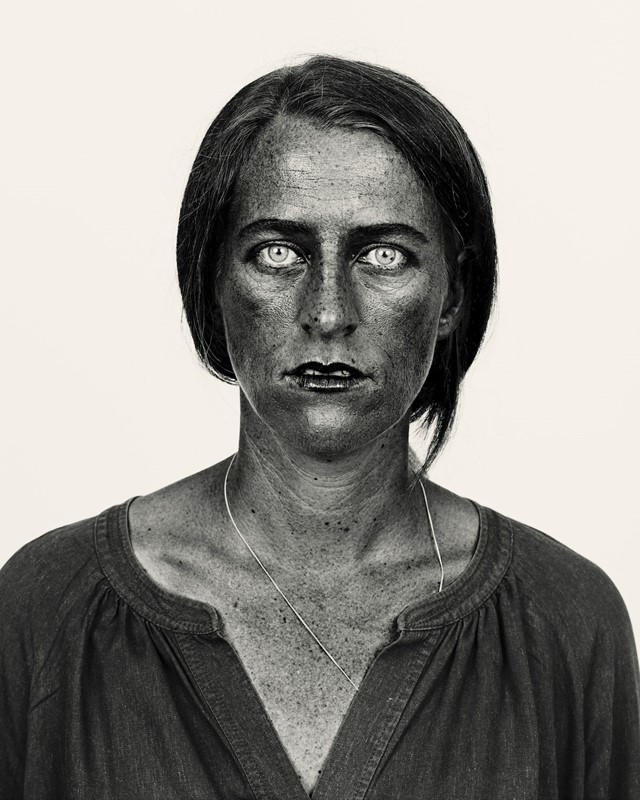

Some photographers use the camera to uphold the status quo, while others use it to question and subvert it. South African image-maker Pieter Hugo has always been part of the latter camp. In his new exhibition, Polyphonic, the artist brings together a wide range of portraits made over the past 20 years which reflect this. And while the subjects are diverse, they all share one formal property: the bust set against a blank backdrop. Doing this, he says, allows him to explore the possibilities and limitations of portraiture. What remains are the “genetics, history, love, trauma, and whatever is left, and whether you can actually know anything about a person,” Hugo tells AnOther, shortly after he finished installing the exhibition at Stevenson gallery in Johannesburg.

Imagined as “neutral”, institutions have also adopted this format to create ID cards, which can be used to allow or deny access. “It enables you to do things like drive a car or travel with a passport, but in Nazi Germany and Apartheid South Africa it was something used to discriminate,” Hugo says. Yet his portraits are not without a certain humanism that transcends the limitations of the format. Whether photographing heads of state, transgender women from Naples known as il femminielli, lawmakers, theoreticians, celebrities, family members, or himself, Hugo’s sitters boldly confront our gaze. Taken individually, they are so singular that they easily resist type. Taken together, they are so expansive that they become an inclusive display of the populace.

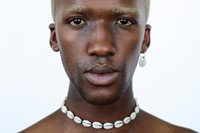

The exhibition takes its title, “polyphonic”, from a music term used to describe the sound of many voices simultaneously producing a melody all its own – which perfectly describes the way in which Hugo has hung the show. The photographs are organised in grids or at eye level to ensure the sitters are active subjects rather than passive objects of the gaze. “When you walk through the show, you are looking people in the eye,” he says, “and I’ve mixed it up so that you have presidents with self-portraits with fashion photographs with people with albinism to keep it democratic.”

Hugo offers a look at the evolution of his own self-image with three self-portraits made at different times in his life. “There is one of me when I was younger and incredibly virile, another of me in drag, and the current one as a middle-aged, irrelevant, overweight, straight male,” he says. “I felt like the critical gaze that I look at the world should come back to me.” Although his most recent self-portrait is unflinching in its brutally honest portrayal of the artist nude and hungover, it also shares the same humanism Hugo brings to his photography. “As I’ve gotten older, I’ve softened the edges a bit and come to appreciate vulnerability – actually cherish it,” he says. “The portrait of me when I was younger was what I wanted to project to the world: strong, assertive and confrontational, but that’s not me anymore.”

The decision to dress in drag came from another place: a nod to growing up among counter-cultural perspectives. Secure in all aspects of his sexuality and character, Hugo recognised the strict limitations the patriarchy has placed upon men to police the performance of masculinity. This image blends perfectly into the choir of visages Hugo has brought together for the show, flowing effortlessly amid images from Solus Vol. 1, his most recent body of work, which brings together portraits of a new generation – many of them gender-fluid models – from all around the globe.

“It’s a duty to experiment and get yourself uncomfortable; creativity comes from new things,” says Hugo, who has followed this principle throughout his career. He points to a project he did years ago photographing blind people, an experience that taught him a tremendous amount about the nature of portraiture. “I felt incredibly self-conscious because you have to physically direct them to what you want,” Hugo remembers. “There’s an incredible discomfort one feels that has nothing to do with the person you are photographing. The discomfort is within you. It’s your biases and issues. That was a major key that unlocked a lot in my practice and understanding. When we engage with people, there are so many small signifiers that go back centuries in evolutionary history about how we read people and situate ourselves to respond to them.”

Hugo’s portraits reveal the inherent paradox of photography: the ways in which the medium moves through liminal space of fact and fiction, image and substance, spirit and flesh. “What a photograph does is tell you about a surface of something, and we imbue meaning into that. Sometimes that meaning is accurate and sometimes it’s not. Every so often it’s read in a completely different way than what I intended it to do, and it acts as the start of a conversation about possibilities and limitations,” he says. “I’ve always been interested in making pictures that hold you and don’t let you go. I look for that exchange of energy between myself and the subject; it’s non-verbal communication but still a collaboration. No matter who you are in that moment, it’s you and I, and that’s it. It’s like a great equaliser in the world.”

Pieter Hugo: Polyphonic is on show at Stevenson gallery in Johannesburg, South Africa until 4 February 2023.