In Holy Night, Issei Suda captures Tokyo’s pre-Christmas shopping frenzy – and the peculiar “awkwardness” of the festive period

For too long, Issei Suda remained largely anonymous in the west. This might be, in part, due to the fact that orientalist fantasies have frequently played out in discourses around the history of Japanese photography. For example, while Nobuyoshi Araki catered to the ideals of sexuality, Hiroshi Sugimoto stood for the aesthetics of zen. An outlier in the generation to which he belonged, refusing to align himself with any of its movements or schools, Suda went about things in his own unique way. If his entire oeuvre could be boiled down to a single concern, it would be the peculiar business of modern living.

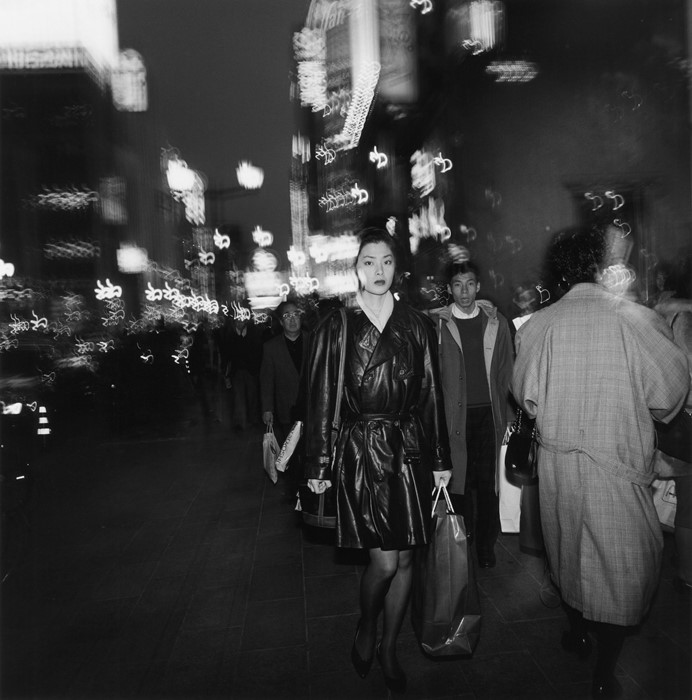

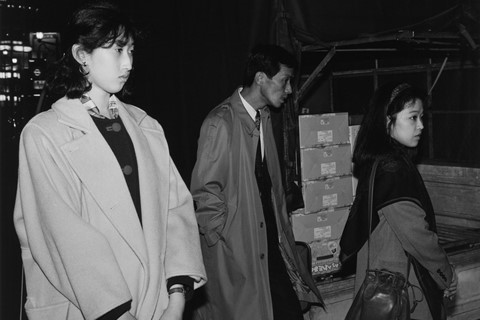

In Chose Commune’s latest excavation of Suda’s pharaoh’s tomb of an archive, the push and pull of old and new is stronger than ever. A stylish book delivered in the square format (Suda’s signature), Holy Night provides a charming tour of Tokyo on the night of Christmas Eve, 1991. Here we have Suda on top, street-shooting form, offering a rich banquet of happenstance: askew angles, uncentred compositions, salarymen with flash-lit scowls on their faces, for they’ve left gift-giving until the last minute. Suda shows Christmas at its most meretricious: a naked celebration of capitalism. That is, the opposite of ‘naked’: warmly wrapped, adorned, sparkling and decorated.

“I wonder how many Japanese people actually think of Jesus Christ on Christmas,” ponders Suda in the brilliantly acerbic afterword. “We just observe Christmas Eve by buying cake and bringing it home to eat; lovers spend it together as the most romantic night of the year. These kinds of customs have become the norm. I could suddenly play the part of the righteous Buddhist and call everyone out on it – you dumbasses, you aren’t even Christians – but it feels like it’d be a waste.”

Suda’s despair should be unsurprising. Here is a photographer who, following a stint at the psychedelic theatre troupe Tenjō Sajiki in the late 1960s, embarked on a quest through rural Japan, capturing the chaos of traditional matsuri (‘festivals’). For Suda, it was not only a return to an emotional landscape that predated western influence and modernisation, but a way of archiving the spirit of old Japan. Yet what if Tokyo’s pre-Christmas shopping frenzy is not the callous manifestation of the free market that it might seem? At the core of these midwinter scenes is something fundamentally irrational but genuine: a need to make merry, to hang mushrooms and squirrels from the metro ceiling, to lavish one another with food and flowers purely because it’s got so dark.

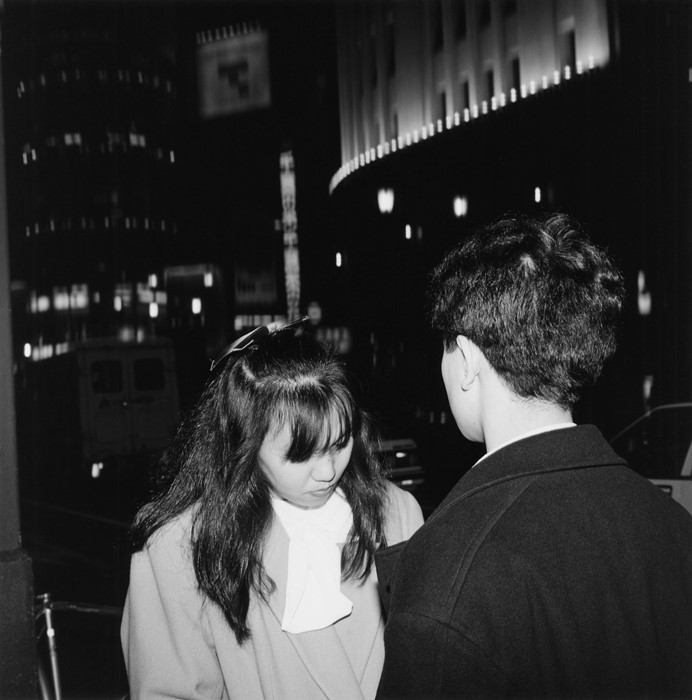

“Christmas is a day of reaffirming faith: the faith of love,” writes Suda. It might be love expressed with money – love bought – but Suda seemed to nevertheless find within these awkward displays a tender performativity not unlike the kind he witnessed back in the countryside. “This is an ordeal of sorts for a nation of people who already fumble with displays of affection. Even the gesture of offering a bouquet here is far removed from what you see in the west. Then the receiver might gingerly bow their head in thanks; both sides look uncomfortable from the moment they meet. I feel like Christmas Eve may be when the Japanese look their tackiest. And people carry this awkwardness with them, as the darkness between buildings sucks them in.”

Sucks them in, indeed … Suda’s snapshots were taken on a cliff edge. Japan’s excesses from years of rapid growth culminated a few months later when, in early 1992, the spectacular asset prices crashed. The country descended into post-bubble blues, entering an era that would be dubbed the ‘Lost Decade’. With this in mind, it is tempting to read Suda’s Holy Night as a pseudo-parable, for its conclusion seems to sum it all up. Exiting a mall with a cake, a woman looks up. The heavens have opened, and Tokyoites are pulling out their brollies en masse. Yet the rain is not enough to clear the streets of shoppers. Nor is it enough to deter our most curious Christmas chronicler, who has found yet another layer of absurdity in the everyday. One is grateful for his investigative eye and, above all, his fondness for what he called “my Japan”.

Holy Night by Issei Suda is published by Chose Commune and is out now.