On first glance, Roe Ethridge’s photographs look like a literal car crash. In the American photographer’s new, MACK-published monograph American Polychronic, noses are bloodied and eyes are bruised, while ashtrays runneth over, and peaches acquire thick, furry layers of mould. “You hear this complaint from art directors: we’ve figured out too many ways to make things perfect, whether it’s a filter, or retouching or whatever,” says Ethridge. “It’s almost like, why would that be a goal at this point? It’s too fucking easy. How do we make this more problematic?”

As an image-maker who has straddled the genres of commercial, art and fashion photography for more than 20 years now, Ethridge has always celebrated the things others would rather look away from. His most well-known images are rife with defects; there’s his doe-eyed 1999 self-portrait, where his preppy good looks are marred only by the multicoloured bruise on his right eye; Andrew WK’s now-iconic I Get Wet album cover, where the American rocker’s nose cascades with blood; Old Fruit, a mouldy still life that appeared on the cover of Vice magazine in 2010; and a Comme des Garçons shirt advert featuring pigeons flapping in mid-air, splaying their feathered wings majestically. “There’s that famous Warhol quote about getting it exactly wrong: ‘when you do something exactly wrong, you always turn up something,’” says Ethridge. “There is a humanity in imperfection that I really like. It’s almost always not conscious, it’s something that just happens. And then you choose it later [in the edit].”

American Polychronic – titled so because the book is structured non-chronologically in reverse (with art and commercial photography interweaving from opposite ends of the book) – features over 400 images taken over the past two decades, some of which have been exhibited at the Whitney Biennial, MoMa and Gagosian (the Tate and the ICA have also collected his work).

Born in suburban Atlanta in 1969, Ethridge had his sights set on photography from an early age. He recalls a memory of finding Kodachrome slides of himself as a child, holding up test shots his father – an “amateur photographer” – had taken. “I guess I was participating in a photographic thing from before my hippocampus was developed,” he says. After discovering the “very American” work of Andy Warhol and Lee Friedlander through his father – two seminal artistic influences to this day – he assisted catalogue photographers in Atlanta. “I loved the crappiness of catalogue photography, and the proletarian version of commercial photography,” he says, comparing the experience of shooting 50 images a day for JCPenney catalogues to that of Warhol’s prolific Factory.

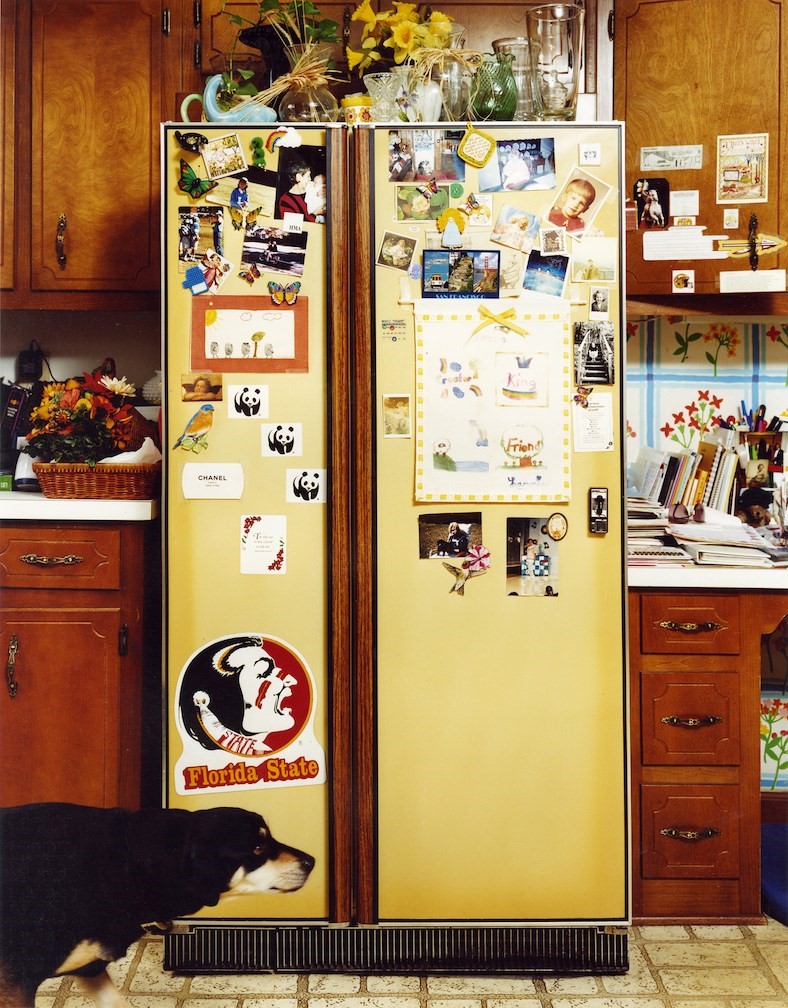

After studying photography at Atlanta College of Art, Ethridge moved to New York in 1997 and had a breakthrough with his approach to image-making. Instead of taking an overly intellectualised approach to photography, he realised that his work was much better when it purely instinctive, although it still seems to retain some kind of conceptual bent. The first photo in American Polychronic is emblematic of this shift – a homey picture of the yellow refrigerator in his Atlanta family home, which was an assignment for the New York Times Magazine – and shows a young artist coming into his own. “The story got killed, but it was one of those pictures that was like, everything. It’s a self-portrait – there’s me on the refrigerator, there’s my dog running in the frame, there’s my mum’s glasses on her little desk and all the Christian stuff … it’s a family history picture.”

Just like his photographs, in conversation Ethridge is simultaneously highbrow and lowbrow, throwing out obscure references to philosophers Roland Barthes and Ludwig Wittgenstein, German conceptual artists from the 1980s, and Greek sculpture, all while giggling knowingly. Humour is a crucial component in his work, with much of the images in American Polychronic playing out like a spoof of the catalogue photography genre; he has an eye for the mundane, the artificial and the tacky – many of his subjects grin widely, but they rarely look like they mean it – but he also exposes the falsity of photography, with watermarked stock images and studio setups clearly exposed. “I think that failure aesthetic is really fun and interesting, especially when it’s inappropriate,” says Ethridge, perhaps in reference to the multiple fashion editorials he’s shot over the years for Dazed, Vogue, Interview, System and more, where models yawn, wrestle, and (shock!) eat food.

Hoardes of well-known actors, artists, designers, and writers also feature in the book, with the list including Chloë Sevigny, Willem Dafoe, Grimes, Dev Hynes, Julia Fox, Cindy Sherman, Wes Anderson, Donna Tartt, Lakeith Stanfield, Laila Gohar, Telfar Clemens, and even Anna Wintour. Does Ethridge enjoy shooting celebrities? “I’m not a person who really keeps up with that stuff. It just happens as a byproduct of being here in New York and being available for editorial,” he says. “But I do enjoy it, even though it’s scary. There’s a social aspect that I don't think everybody would have the stomach for, but for whatever reason I do.”

Outside of celebrity though, Ethridge’s work feels distinctly American, although how it does is difficult to define. Maybe it’s the psychedelic, stoner undertone of the book, or the fetishistic shots of American Spirit cigarette packets, suburban homes, winding highways, fratty men in sports gear, and a preoccupation with violence and the marks it leaves behind. “The time when I was in school was the birth of what we call identity politics. I remember thinking, I’m really, like, nothing. I am a suburban male from America. It’s as generic as you can get. Middle class, everything is just right in the fucking middle. So boring,” laughs Ethridge.

In Ethridge’s photographic universe, chaos reigns, and there is meaning to be gleaned from looking at his images closely. “I mean, I don’t understand them [my pictures]. The shooting part is not intellectual, it’s more intuitive, it’s messy,” he explains. “I’m like a wild beast, a creature gathering, taking pictures. I’m responding as intuitively as I can. I can understand that feeling of ‘what the fuck is going on?’ when you look at my pictures, but that is kind of what I think too, you know?”

American Polychronic by Roe Ethridge is published by MACK, and is out now.