In 1993, Gideon Mendel spent several weeks photographing patients at the first dedicated Aids ward in the UK. Here, in his own words, he talks about the groundbreaking project and its legacy

“The Broderip Ward was different,” says Sarah Macauley, a nurse at London’s Middlesex Hospital. Opened by Princess Diana in 1987, it was the first dedicated Aids ward in the country. “Everybody died, and they were my age, but there was also a lot of fun,” she recalls. “That was the strange thing about it. It was probably the place I had the most laughs.” Sarah once went to check on a patient and found his bed empty. “Where is Steven?” “He went out clubbing,” she was told. “He just hasn’t got back yet.”

Steven was one of four men photographed by Gideon Mendel over several weeks in 1993. Designed to mark the tenth anniversary of the Terrence Higgins Trust, The Ward captured how patients and staff transformed the constraints of hospital life and what a terminal ward could be. “I realised quite quickly that there was something special going on,” Mendel tells AnOther. “So I feel … not quite a burden, but a responsibility in my stewardship of these photographs.”

Now, thirty years later, Mendel has revisited the project with a film installation at the Fitzrovia Chapel, the last surviving building of Middlesex Hospital. On view until February 5, the film combines previously unseen images with interviews of staff and family members, screened before a secular altar. “On a Saturday, the ward was like a bar in the West End,” says Sarah in the film. “All those things that were part of life. It was trying to bring that into the ward.”

Below, in his own words, Mendel reflects on The Ward and its legacy.

“The Ward was originally commissioned as part of Lyndall Stein’s Positive Lives project. It was trying to move away from the victimology and the extremity of the conventional documentary response. I think the expectation when people think of images of HIV and Aids is going to see emaciated, dying, sad situations. And of course, the background to it was death. There was no effective treatment [until 1996]. But what you saw at the Broderip was so much visible joy and love and connection. It’s been slightly forgotten now, but it was a big exhibition at the Photographers’ Gallery and quite a cultural milestone.

“It was in some ways an impossible challenge. There were so many people who couldn’t be photographed and confidentiality was such an issue. That was really because a lot of people who were infected, their families didn’t know they were gay. There was such fear and stigma. But certain people really wanted to be photographed. I think because what I offered them was a kind of witnessing. Everyone knew they were dying. So I think these four men, very remarkably, and very bravely, wanted to be witnessed and to be shown in order to fight stigma, in order to fight the disease.

“It’s very interesting to me that these pictures have actually gained velocity with time. Time does funny things to photography. We would never have imagined at that point that dealing with HIV would be so different for young people today than it was then. Now if you can access treatment, you can live a relatively normal life. But in my other work Through Positive Eyes, which is a collaborative project working with HIV-positive people around the world, the one thing that prevents that is stigma. The ongoing stigma around HIV is still a massive problem.

“Everyone who was part of that ward – the doctors, the consultants, nurses, social workers, family, friends – it was like an axis with lots of personal lines going through it. Everyone was affected by it. Patients were really active in pushing the medical responses and demanding drugs. There was patient activism that was completely unprecedented, and that was a global phenomenon. Some patients were very knowledgeable. The medical staff really embraced that.

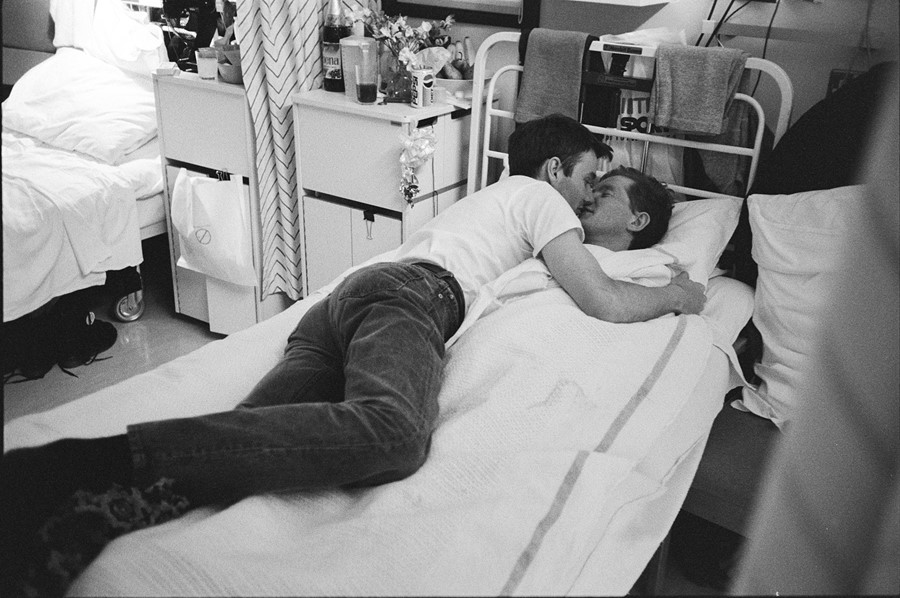

“I realised very quickly that what I was seeing was quite unique and wonderful. Just seeing patients being allowed to be very intimate with their partners and families. It’s documented with John, seeing people being able to lie down and embrace. It was a particular kind of feeling that gay intimacy was very much allowed. And I think it’s that intimacy that means people can look at these photographs and feel engaged by them. What is really interesting to me is the response we’re getting to the presentation. For people who aren’t connected to the medical world, or to HIV, the response really seems to be meaningful. Every day more and more people are coming.

“You can draw a direct line between this act of remarkable bravery by these four young men and the fact that young men their age today can access effective treatment and don’t have to deal with that kind of stigma. The images were so publicised, as well as their stories, that they were very much part of the mobilisation to develop treatment to make it more widely available. So I have huge admiration for them. Their bravery is actually part of the reason why it’s not the same problem today.”

The Ward – Revisited by Gideon Mendel is on show at The Fitzrovia Chapel in London until 5 February 2023. The accompanying book is available to buy here.