“There are good artists that have children. They are called men,” Tracey Emin famously remarked, explaining that motherhood would “compromise” her work. She’s not alone in this belief: Marina Abramović similarly told the German newspaper Der Tagesspiegel that she had three abortions, because she was certain having children “would be a disaster” for her work. “One only has limited energy in the body,” she said, “and I would have had to divide it.”

Not holding back, Abramović claimed that motherhood is “the reason why women aren’t as successful as men in the art world”. Yet today many contemporary artist mothers are not only juggling parenthood with a successful career, but also taking it as a vast source of inspiration for their subject matter. Isn’t it about time that we saw motherhood not as a hindrance, but as a real asset, for the art world?

Historically, motherhood has undoubtedly been perceived, by artists, dealers, critics and curators alike, as career suicide. “The exclusion has been twofold – affecting both the artist herself, and motherhood as a subject”, says art critic Hettie Judah, whose book How Not to Exclude Artist Mothers (and other parents)’ was recently published.

On a practical level, the art world has not exactly been set up to accommodate children: wine-fuelled private view evenings, demanding exhibition installation days, residencies and studios without nurseries on-site all form very tangible barriers for parenthood. In relationships between artists, it is traditionally the woman who has assumed responsibility for childcare, enabling their male partners time alone in the studio, while having to pause their own practice.

“For centuries, art by women was considered inferior,” says Judah. “The domestic sphere was the woman’s realm and was thus considered a minor subject for art.” Major female Impressionists have been sidelined for their focus on mothers and babies in the home and private gardens, and it’s an attitude that lingers on: “Even today, art students are discouraged from making work about motherhood and told it is not a subject for serious art,” says Judah. This position feels particularly unfair given that men have often not experienced the same prejudice. Instead, the motif of the mother and child is one of most enduring in Western art history, with the likes of Leonardo da Vinci, Caravaggio, Raphael, William-Adolphe Bouguereau and Gustav Klimt being lauded for their take on this subject, considered significant in their hands.

Men have also been praised for taking their own children as subjects. Thomas Gainsborough painted his two daughters frequently, with much-loved depictions of Margaret and Mary hanging in major museums worldwide, while Renoir’s romanticised portrayals of Madame Renoir and their son Pierre have made millions of dollars at auction. Moving into modern art, Marguerite Matisse starred in several of her father’s paintings, while Picasso – who took his daughter Maya as a muse – was celebrated for linking childhood and creativity.

This biased history of art, then, begs the question: why should women not also be commended for taking parenthood as the source of their inspiration? Answering back, a growing number of contemporary women artists are beginning to tackle the age-old taboo and openly embrace the theme, reframing their own children, other mothers and selves as inspiring muses.

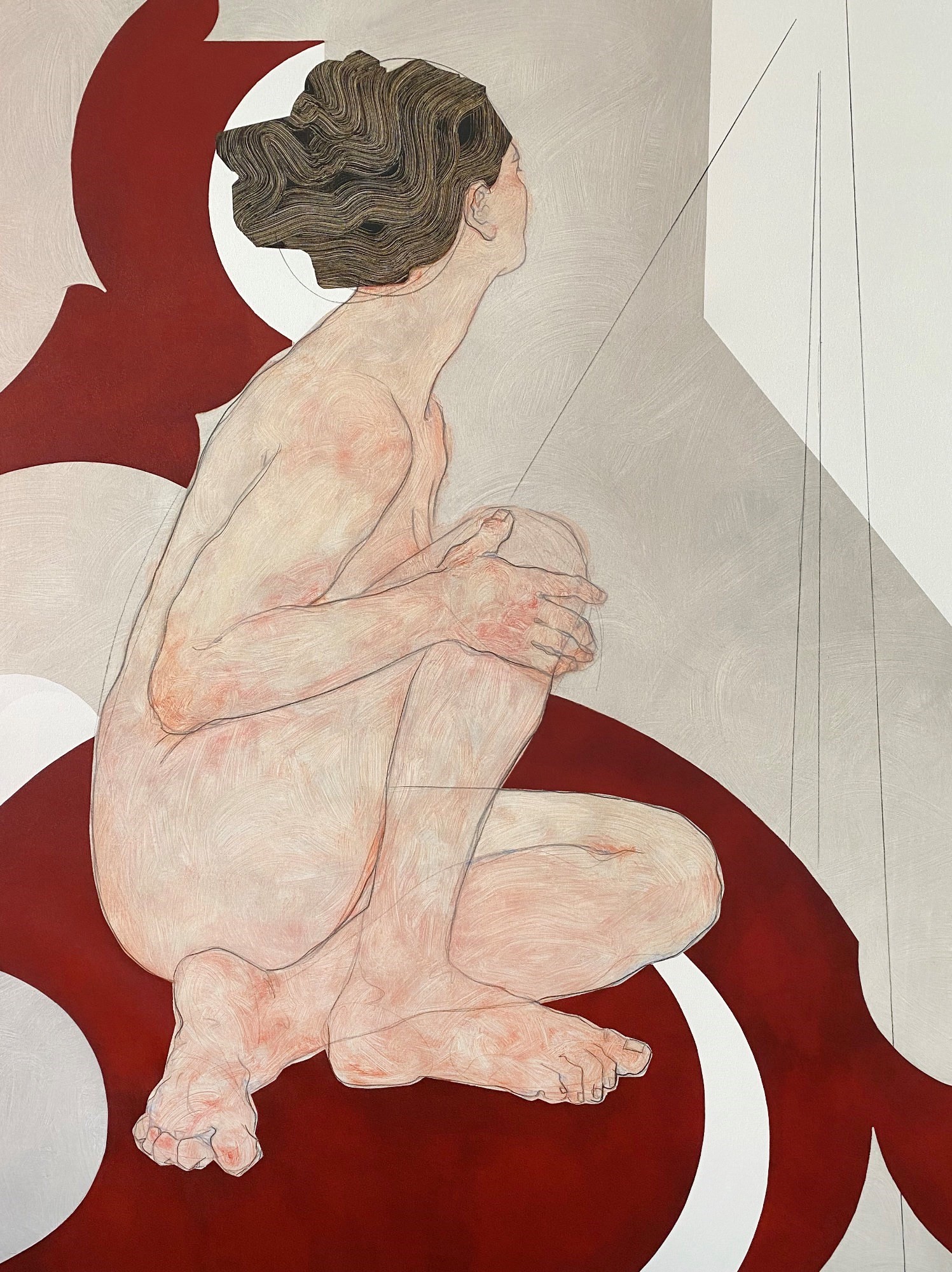

Offering viewers a far more authentic and expansive view of motherhood than their male counterparts, contemporary women artists are increasingly receiving recognition from commercial galleries, art fairs and museums. Represented by Rebecca Hossack Gallery, Nikoleta Sekulovic is one such artist who, since becoming a mother herself, has been on a self-proclaimed “mission” to “portray the modern-day mother as a muse” through her paintings. “They are a source of inspiration that too often goes unnoticed,” she explains. “We are not in the habit of acknowledging them as such, but they are. Their lives however are usually so packed, especially mothers with small children, that they don’t often have the time to feel like muses. Hence it is unique and empowering to give them this moment, a moment to stand still in time, eternally on canvas, not pretending or trying to please anyone, just uniquely themselves.”

Meanwhile, Scottish-born Chinese figurative painter Elaine Woo MacGregor directly reflects on the relationship with her two mixed race children, Carina and Ramona, who feature in her most recent series, Maman et Muses. Through complex, coming-of-age scenes, she frames important fleeting moments of time, memories and the psychological intimacy she has with her children.

Her work also points to a forever-shifting relationship as her children inevitably grow up, taking the viewer “beyond a likeness portrait.” Paintings such as Bathers in Avon (2022) are based on true events: the artist recalls the summer of 2021 when “the children were very carefree and going wild swimming in our local river (Avon) in Linlithgow. I wanted to capture the spirit of the youth and a sense of electricity (especially considering the atmosphere at the time during the global pandemic).” There’s an indistinct quality to many of Woo MacGregor’s scenes. It’s as if she is protecting her personal sitters from too much scrutiny or close observation by the onlooker, deliberately creating surreal, dreamlike narratives.

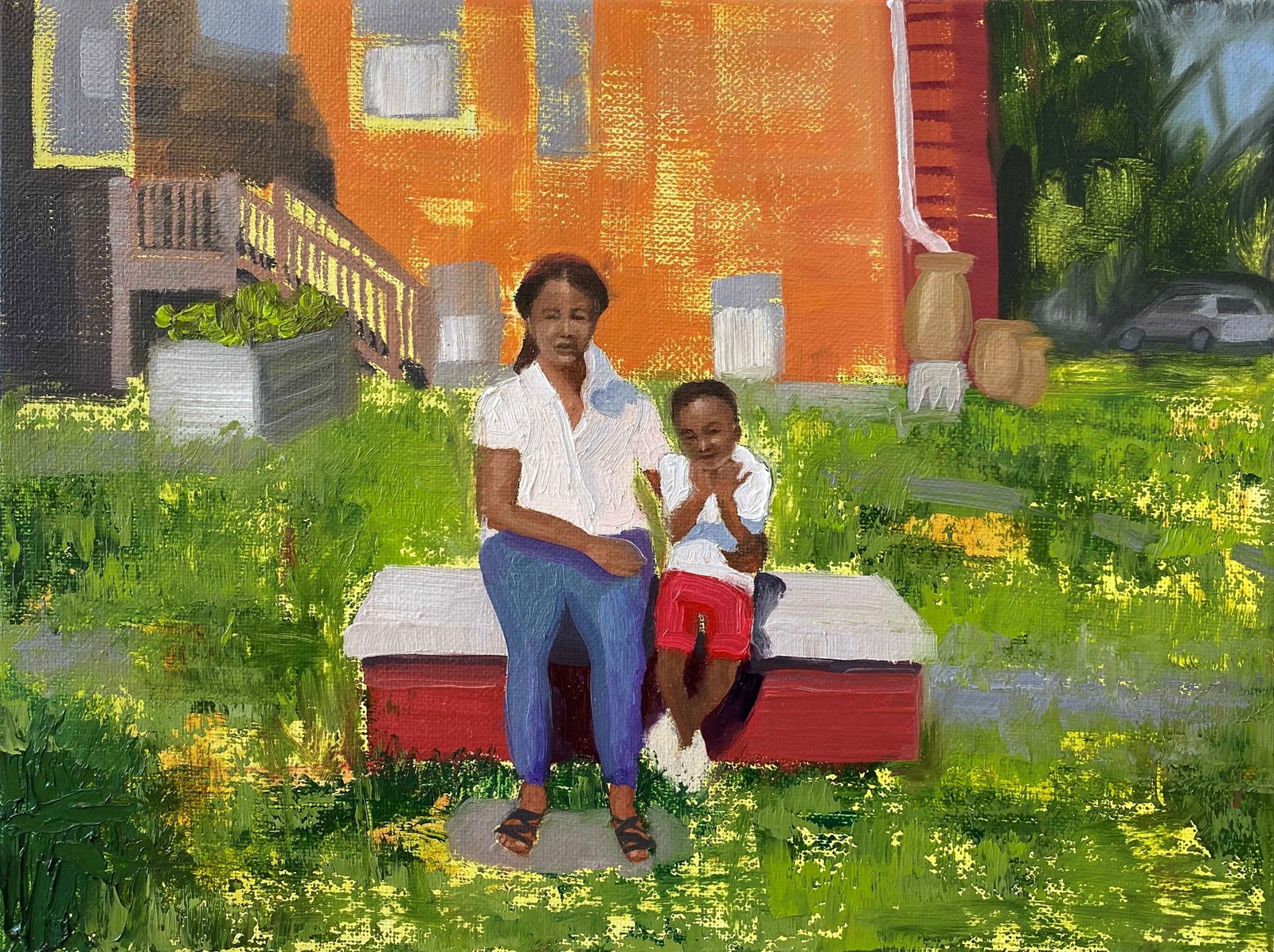

In contrast, the personal becomes political in the paintings of American artist Ashley January. It was her own traumatic pregnancy and the survival of her prematurely-born son that has informed January’s unfiltered paintings of Black mothers and small children. Centring her subjects’ experiences, with motifs structured around the rituals of care, she addresses the Black maternal mortality and morbidity crisis in America, where Black women are three to four times more likely to die from pregnancy-related complications than white women.

As January explains, her images are meant to “serve as a global call to action for more awareness, research, and the eradication of unnecessary maternal and infant death.” Redefining and subverting art history’s mother and child motif, she shares a powerful and timely message on behalf of her subjects. Deliberately naming them through her titles and portraying them with humanity, she presents them as real people, rather than statistics, who deserve to be treated with equal care.

Historically, the subject matter of motherhood has not been taken seriously when created by a woman, but that’s exactly how artist-mothers such as January are demanding that their work is seen. Rejecting overly-romanticised views of motherhood, the artist shines a light on the vital issues and uncomfortable truths faced by mothers, and she is finding a platform for it. Through solo shows and group exhibitions January is sharing her work – and message – with audiences in both the US and UK.

“There has been a generational shift. Many of my contemporaries felt they wouldn't be taken seriously if they had children – if they did become mothers, that side of their identity was kept out of sight,” explains Judah. However, pioneers such as Chantal Joffe, Ishbel Myerscough, Louise Bourgeois and Jenny Saville have undoubtedly paved the way for the next generation. “Artists in their thirties increasingly feel empowered to make their identities as mothers public. I think social media and the pandemic have also played a role in normalising the public sharing of details of our private lives.”

Looking ahead, the art world must better understand the needs of, and make space for, artist-mothers. As Judah proposes in her manifesto, it’s essential that the artist is treated “as a whole person”. Where relevant, this includes giving a platform to their representations of the enduring theme of motherhood, which is a central aim of the curated exhibition Reframing the Muse at London Art Fair.

Expanding notions of who and what a muse is – beyond tropes of the submissive young female model – this exhibition centres and reveres the maternal gaze as it falls upon the artist’s own body, other mothers and children. Featuring Ashley January, Nikoleta Sekulovic and Elaine Woo MacGregor, among others, this show intends to prove that there are great artists that have children. They are called women.

Reframing the Muse – curated by Ruth Millington, author of Muse (Penguin, 2022) – is on show at the 2023 edition of London Art Fair, which runs from 18-22 January 2023.