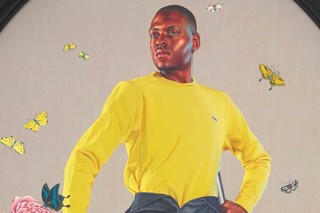

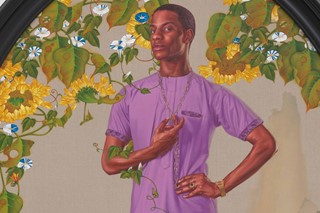

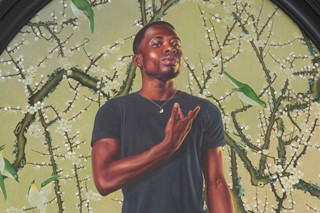

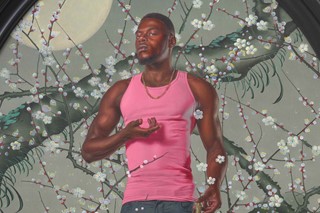

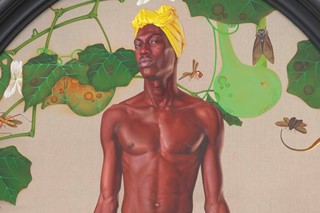

Kehinde Wiley is the widely acclaimed LA-born, New York-based artist known for his large-scale, maximalist portraits of contemporary Black figures. Often, the people in Wiley’s paintings are passersby scouted in the streets of cities around the world like Mumbai, Dakar and Rio de Janeiro. His figures, usually backdropped by vividly coloured floral patterns or landscapes, are portrayed with the precision of his signature, hyper-realistic style of oil painting. They mimic the poses found in historical portraits of nobility and royals, because, in Wiley’s own words, his figures are “demanding to be taken seriously, and demanding not to disappear”.

In his new exhibition Colourful Realm at Roberts Projects in LA, Wiley takes a more minimal approach to painting. Much of his inspiration for this series comes from Japanese landscape paintings of the Edo period; while growing up in California, Wiley’s mother would regale him with stories of living in Japan as a marine, and she would often prepare Japanese meals at home. As a result, Japanese culture has always had a strong influence on his artwork.

Using his deep knowledge of painterly traditions in both Japanese and western art, here, Wiley has produced a body of work that feels fresh and liberating. In these portraits, he is “imagining a new type of freedom” for the Black body. Below, he talks AnOther through the new show.

Alayo Akinkugbe: Let’s start with the title of this exhibition, Colourful Realm, which references Images and the Colourful Realm of Living Beings (Dōshoku Sai-e), a scroll series by the 18th-century Japanese painter, Ito Jakuchu. What drew you to Jakuchu as a source of inspiration?

Kehinde Wiley: Well, it’s about him, certainly. But it’s also about Edo period landscape paintings at large. It’s a type of painting of the landscape that is decidedly non-western, that is obsessed with perspective, but [that] finds answers in a series of different ways. It comes from a different cultural point of view. It makes different assumptions about what land is, what territoriality is, what the relationship between man and nature is and … this is kind of fascinating to me.

I was first drawn to Japanese landscape painting by my mom. She was born and raised in Texas, in a small town called Downsville, and she joined the Marines and moved to Japan as a means of getting out of sharecropping in the south. And so when we were growing up in California, she would tell us so many stories about Japan and prepare Japanese meals and so on. It became a very familiar aspect of my childhood.

Years later, when thinking about breaking through western romantic notions of the landscape and man’s relationship to it, I wanted to be able to draw up on non-western models of freedom of space, and particularly, figuring Black bodies within that space, imagining a new type of freedom possible.

“I wanted to be able to draw up on non-western models of freedom of space, and particularly, figuring Black bodies within that space, imagining a new type of freedom possible” – Kehinde Wiley

AA: There’s a sense of stripping back in this series: the exposed linen in the background of these works, like Edo period landscapes, gives a more minimal feel to the portraits compared with some of your earlier works. Have you enjoyed making more minimal compositions?

KW: Definitely, there’s something nice about being able to create a sense of quiet. So much of my early work was, like, blinged out – decidedly about American hip-hop and about a sense of maximalism. And here you have an economy of quiet; a space in which the value is on how much it whispers. [The linen] is also just a beautiful colour to leave exposed. Oftentimes I tinted it in certain ways, so some of the paintings are warm, some are cool. It’s a really fun and experimental body of work.

AA: I can see a parallel between the high level of detail in Jakuchu’s work and the hyperrealism of yours. It seems like you’ve taken influence from both western portraiture and Edo period landscapes.

KW: I’m drawing on some of the rhetorical strengths of western easel painting as well as Edo period landscapes. The poses that each of the models are taking on come from aristocratic and noble portraits in western painting. There’s the use of oil paint, there’s the scale that’s about domination, about history painting. So it’s really this back-and-forth conversation between a much more quiet sensibility and the chest-beating rhetorical strength of western easel painting.

AA: You base all of your figures on real people, who you sometimes scout on the street. How did you choose the figures who posed for these paintings?

KW: Most of my work portrays people who I happen to chance upon and some of them are friends and family. With this particular body of work, I actually went back through models that I used before in prior paintings. So it’s like a little ‘best of the career of Kehinde Wiley’, with a peppering of a couple of friends as well.

For instance, it’s really wonderful to be able to see [my friend] Denola in this work, because I’ve been wanting to paint him for a number of years. We had the opportunity to shoot when I was in Dakar and he was also in Senegal. As luck would have it, I was looking for a model for this series and it worked out perfectly.

AA: Finally, what is the effect you want these large-scale portraits to have on the audience?

KW: The figures are designed to sit in the space in a kind of sculptural way. They’re designed to contend with you physically as a viewer.

Colourful Realm by Kehinde Wiley is on show at Roberts Projects in LA until 8 April 2023.