Gideon Appah’s first UK solo show combines elements of Ghana’s postcolonial history with his typically vibrant renderings of otherworldly fantasy. The resulting paintings are “out of time, out of place,” he explains

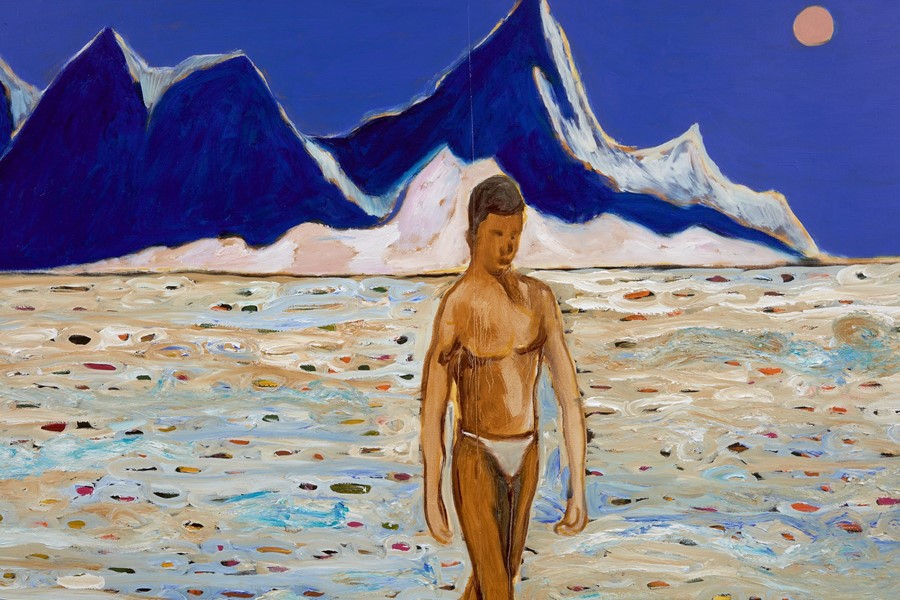

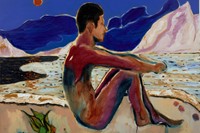

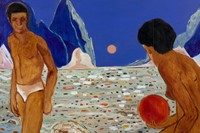

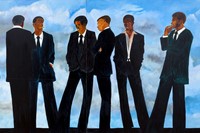

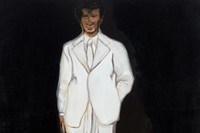

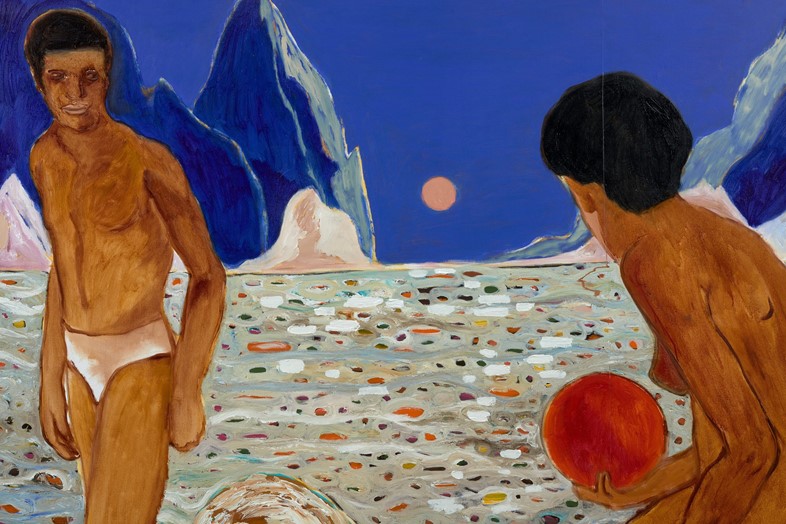

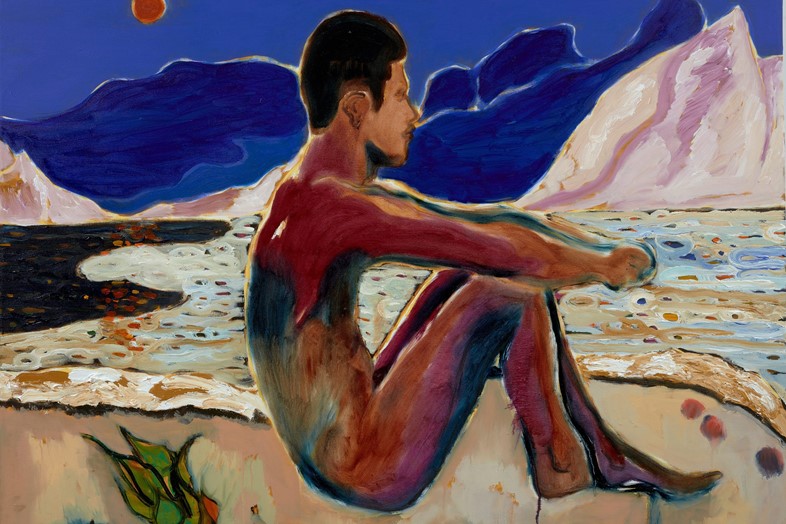

In his mystical, jewel-like compositions, Ghanaian painter Gideon Appah suspends time beyond past, present and future. His intensely colourful canvases are populated either by nude or semi-nude figures languishing in a private eden, a tranquil, prelapsarian world, or by suited men smoking outside a nightclub, reflecting these shifting temporalities. These often fictitious characters, painted in varying hues of ochre and ultramarine, emanate from old newspaper entertainment columns and vintage Ghanaian film stills as well as the artist’s vivid imagination.

For his debut solo exhibition in the UK, and his first with Pace Gallery since joining their roster last September, Appah presents eleven new works that distil the most exciting elements of his blossoming practice. Building upon the success of last year’s landmark exhibition at the Institute for Contemporary Art in Richmond, Virginia, How to Say Sorry in a Thousand Lights sees Appah combine elements of Ghana’s postcolonial history with his typically vibrant renderings of otherworldly fantasy.

Appah is an artist for whom found images provide ignition. For this exhibition however, he initiated the process himself, exploring Ghana’s coastline along the outskirts of Accra in search of abandoned buildings to photograph. What he discovered comes to the surface in the ghostly tranquillity of Night Vision, in which the shimmering form of an island fort, illuminated by a celestial night sky, is reflected in the surrounding water. This could well be one of the 40-odd castles along Ghana’s coast originally built to incarcerate slaves before they were sent on the perilous Middle Passage. The fort’s spectral presence and colonial connotation are embraced and reworked by Appah into something akin to an outpost of the underworld, reminiscent of Arnold Böcklin’s Isle of the Dead (1880).

In other works, Appah draws upon Ghana’s postcolonial cinema and the emergence of Ghallywood as a harbinger of the country’s new national identity. “I’m obsessed with old Ghanaian movies,” he says, scrolling through endless film stills that he has saved on his phone. From Mr Mensah Builds a House (1955) to Kukurantumi: Road to Accra (1983), these films not only provide images as inspiration, but reflect a period of mass urbanisation in Ghana’s history, during which Accra’s population grew rapidly and the prevalence of independent cinemas allowed the capital’s nightlife to thrive. “These movies spoke more about everyday life, about new possibilities the country was starting to open up to,” explains Appah. This newfound freedom is manifested in the louche poses and sharp sartorial silhouettes of Cloud Men, a continuation of previous paintings like Roxy 2 that could be a nod to Barkley L Hendricks’ iconic white-clad figures in What’s Going On (1974).

At the centre of this exhibition, however, are Appah’s exquisitely hallucinatory depictions of water, which repeat across five of the nine works with subtle variations in tone and texture. Using a black primer on his canvas, Appah coaxes light from dark, initially using oils as underpainting before applying layers of acrylics in some areas and scratching layers off in others to create a kaleidoscopic tapestry of colour. “I wanted to do something to make the water more interesting,” says Appah. “[This technique] makes it dreamlike. It’s a different world.” Inspired by the proximity to the sea from his studio on the outskirts of Accra, the flattened perspective of mountainous backdrops in these works contribute to the sense of being, in the artist’s words, “out of time, out of place”.

In The Sensitivity of Everyday Things, Appah reduces any sense of perspective further still, surrounding the busts of two men with an assortment of objects and disembodied hands. In his reduction of a wider story to a collection of broken fragments, the work recalls Fra Angelico’s San Marco frescoes, particularly The Mocking of Christ (1440), in which the full spectrum of Christ’s tribulations is reduced to a series of disembodied hands and other iconographic symbols. The same is true of Appah’s work more generally, whose dense evocation of narrative and symbolism expands into a much wider myriad of interpretation, inviting viewers into a world of fantasy and enigma that is impossible to resist.

How to Say Sorry in a Thousand Lights by Gideon Appah is on show at Pace Gallery in London until 15 April 2023.