A new photography show in New York featuring works by Buck Ellison, Jesse Gouveia, Jack Pierson and more explores pertinent questions of American-ness, masculinity, and race

What does America look like today? Or, more specifically, what does its image look like? This question is the driving force behind a new group show, Photography Then, at Anonymous Gallery in New York. Featuring works by six photographers – Buck Ellison, Jesse Gouveia, Jack Pierson, Alyssa Kazew, Chessa Subbiondo and Thomas Polcaster – made between the mid-2000s up until the present day, the show addresses questions of American-ness, masculinity, and race – although, like all good exhibitions, it asks more questions than it answers.

Curator KO Nnamdie initially came up with the idea for the show after a younger colleague showed him a TikTok on photographers like Juergen Teller, Terry Richardson and Richard Kern. “It made me think about how all generations inevitably look to the past,” says Nnamdie, “and it made me think about what’s happening right now in image-making.” The title of the show, Photography Then, is a tongue-in-cheek reference to museum survey shows that try to capture the zeitgeist of photography ‘now’, but inevitably fail; these exhibitions can take years to prepare, so by the time the images are hung on the wall, they’re no longer new. Instead, doing shows at smaller commercial galleries such as Anonymous offers an opportunity to “be flexible enough to know what really is happening on the ground”, explains Nnamdie, and act quickly and accordingly.

Having worked as a photographer himself for ten years before moving into curating, Nnamdie is uniquely attuned to the medium and the quirks of its community. In fact, the notion of community is at the heart of all his work; in 2018, he launched Restaurant Projects, a curatorial practice and art advisory whose exhibitions would always end in intimate dinner parties for whoever showed up – a world away from the art world’s more traditional, formal dinners. His latest exhibition, Photography Then, also aims to put the photographic community first. “I understood it to be really hard for photographers to meet face to face, and really see each other as human and not just as something on the screen,” he explains. “Plus, photography is rarely celebrated in exhibition spaces.”

The show consists of eight images made by photographers of older and younger generations, all of whom are based in the US, but with a specific emphasis on emerging talent. “I really wanted to show a picture of America right now,” says Nnamdie. “There is also a very knowing awareness of [the fact that the images] are mainly of white people staring at you.” This statement rings true; Buck Ellison, who has built a career shooting America’s ultra-rich, has an image in the show of a preppy, all-white American family Christmas card, while Alyssa Kazew’s Boys! Boys! Boys!, features five shirtless, grinning young men standing on a verdant front lawn – an image that harks back to the ripped Abercrombie & Fitch hunks of yesteryear. “It really makes you think about the past and how beautiful it was,” says Nnamdie. Jack Pierson’s Blake (2005) features a muscular young man in a red polo shirt leaning against a white Mustang, except the image has been reprinted this year, and creased like a poster. “By folding the page and then having it tacked on the wall, Jack is speaking to [the idea of] idol worship,” says Nnamdie. “He’s speaking to the centrefold, he’s speaking to Playgirl, Playboy … he’s speaking to desire in such a pure way.”

Instead of seeing the show as a critique of whiteness, Nnamdie feels that it’s merely a reflection of the times we live in. “I can’t deny the fact that I am an immigrant,” says Nnamdie, who was born in Nigeria but raised in the US. “But this is not only my story of what I think the American dream is – it’s what the American dream that was sold to me and every other foreigner is. This is what we aspire to.”

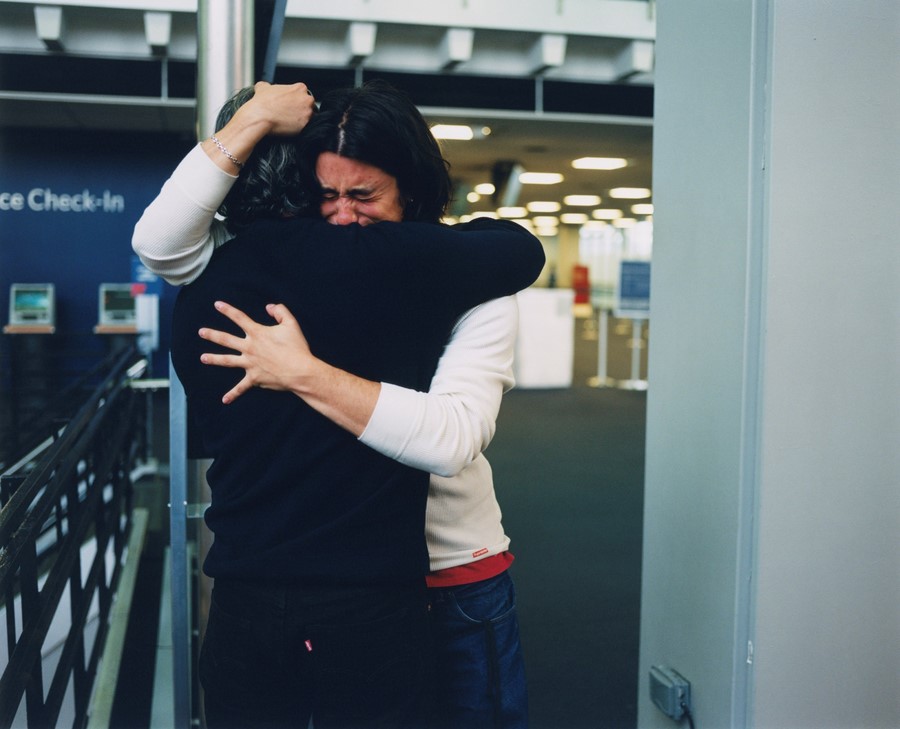

The most striking image in the show – and the one that has created the most buzz – is by Jesse Gouveia, a self-taught, New York-based photographer who has previously shot Frank Ocean and Pharrell Williams for the Financial Times’ HTSI magazine. An emotional self-portrait, Saying goodbye (2022) features Gouveia hugging his father tightly in an airport terminal, sobbing. “What’s great about this image is that Jesse is sharing his vulnerability and piercing this bubble of masculinity that is ever-present in the room,” says Nnamdie. “It’s very intimate, very tender … and I loved that.” On closer inspection of the image, two tiny red clothing labels can be made out – Gouveia is wearing a Supreme top, while his father is wearing Levi’s jeans. “What is funny about the photo is that it’s plugging American brands at the same time, even though it’s not an ad,” Nnamdie says. On the wall behind the image is a photo mural titled Archways, which pictures Gouveia’s parents’ bedroom on their wedding night in 1988, pranked with mountains of toilet paper – an origin story, if you will.

Despite the spotlighting of “beautiful people of privilege” in the images, Nnamdie points to the eerie, unnerving quality of the show. Chessa Subbiondo’s image of American influencer Addison Rae, for example, echoes David LaChapelle’s photo of Britney Spears at a hot dog stand in 2000. “At the time that Britney Spears photo was taken, politically, things were not going so well in America,” says Nnamdie. “But our images told us otherwise, and our pop stars told us otherwise … I do challenge the viewers of this show to really think: why does this look so familiar? Why do I like it?”

Photography Then is on show at Anonymous Gallery in New York until 15 April 2023.