In 1980, Patrick D Pagnano went on assignment at Brooklyn’s legendary Empire Rollerdrome venue. The resulting images, compiled in a new book, capture the heart and soul of roller skate culture

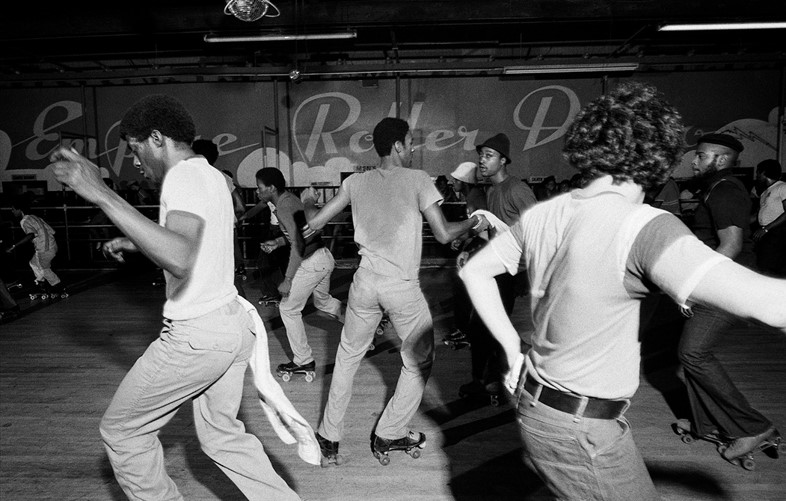

For more than 65 years, Brooklyn’s Empire Rollerdrome stood as a beacon from its sumptuous perch in Crown Heights as the heart and soul of roller skate culture. From the start, the Empire lived up to its name, featuring “miracle maple” floors, elegant wood-panelled walls, and a state-of-the-art sound system – the first purchased from the 1939 World’s Fair and the last designed in 1980 by Richard Long, the mastermind behind the systems at Studio 54 and Paradise Garage.

But it was the skaters themselves who launched Empire into the stratosphere. In 1957, new owners Henry and Hector Abrami introduced the first New York State Roller Skating Championship in 1957, bringing creativity and competition into the spotlight. That same year Detroit native Bill Butler, aka the Godfather of Roller Disco, made his Empire debut. Decked out in his Air Force uniform with a copy of Night Train under his arm, Butler, who went by the name Mr. Charisma, slipped the record to the DJ, hit the floor, showing off his skills, and setting the stage for a revolutionary movement in dance sport.

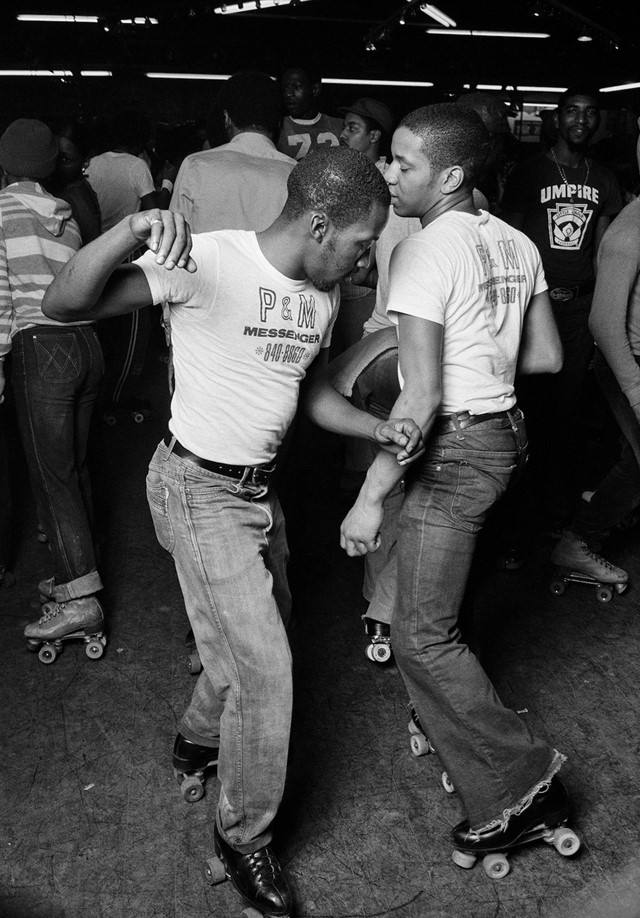

By the 1960s, Empire was at the vanguard of a new era, creating signature styles like the ‘Brooklyn Bounce’. After Butler convinced Gloria McCarthy (Henry’s daughter and a roller skating champion in her own right) to start Bounce Night on Fridays – and it was on. Roller boogie, which embraced jazz, funk, R&B, and dance music, reached its apotheosis with the explosion of disco music in the mid-1970s. But unlike the posh nightclubs in Manhattan, there were no velvet ropes or VIP sections at Empire. All were welcome to groove in style.

“We used to call it roller rocking,” Butler told Rolling Stone in 1979. “All they’ve done is change the names around. Black people have been jammin’ on skates for as long as I can remember. But the terms aren’t important – it’s the skating. It’s the way of moving your body.”

As the roller disco spread across the country, Hollywood took note. Cher hosted the release party for her disco classic Hell on Wheels at Empire, with Butler as her guest – and soon he was consulting on the roller choreography for cult classics like The Warriors (1979) and Xanadu (1980), a musical fantasia starring pop sensation Olivia Newton-John and dance legend Gene Kelly in his final role.

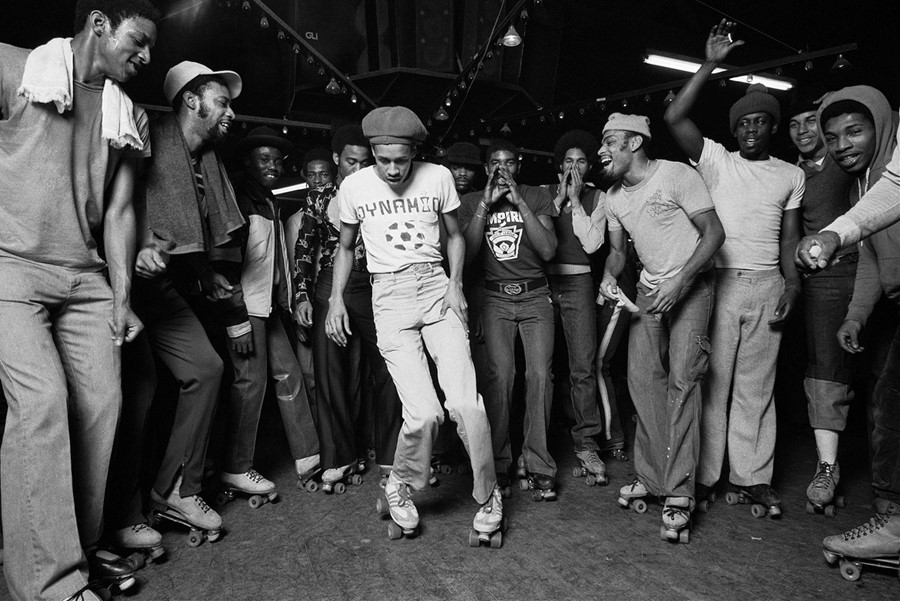

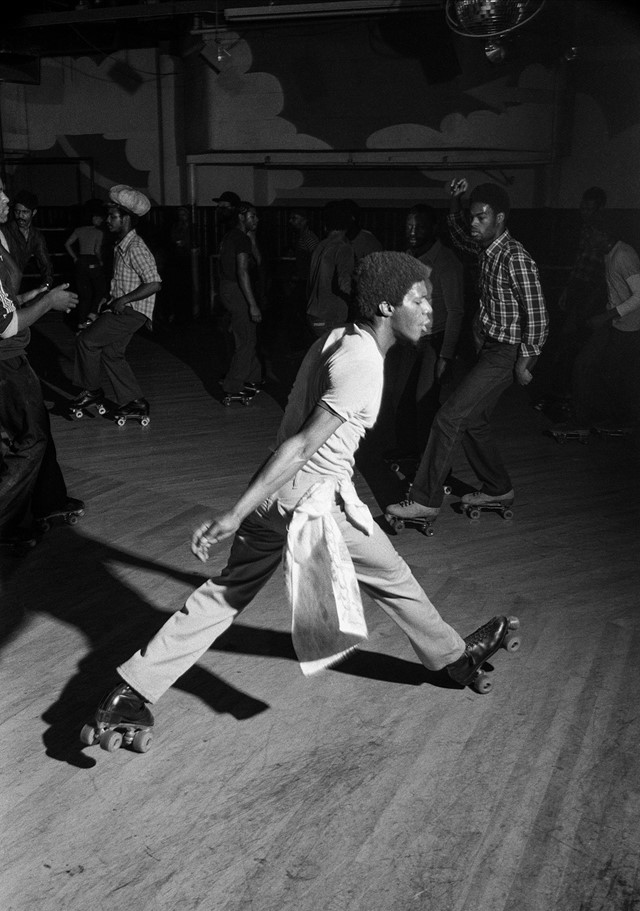

By 1980, the roller disco phenomenon had captivated the nation, striking the perfect balance between dance, music, fashion and creativity – and the mainstream media was hooked. On assignment for a major magazine, photographer Patrick D Pagnano arrived early at Empire one night in February 1980 to set up the lights, and then stepped back so that the rink could reach optimal capacity. Then, with the grace of a dancer, he stepped into the throng, moving at one with the ever-flowing energy of the skaters surrounding him.

Although the story never ran and the contact sheets and negatives were boxed up for nearly four decades, only to reemerge toward the end of Pagnano’s life, when he rediscovered and exhibited them in Brooklyn Photographs, a 2016 group exhibition at BRIC in Brooklyn and a 2018 solo show at Benrubi Gallery in New York City. “Pat was thrilled. It was such a reward after struggling for so long,” says Kari Pagnano, his wife of over 40 years. “It was a beautiful tribute at the end of his life.”

But only a mere handful of the works Pagnano made that night were shown – until now. On April 4, the series will be published in full in the new book Empire Roller Disco (Anthology Editions). Shown in black and white, the series fuses Pagnano’s passion for street photography with his skills as a photojournalist.

Floating in the eye of the storm, Pagnano watched as skaters gave their bodies to the music. “Pat would move in and out of situations seamlessly,” says Kari. “When he was on the street, people might be looking right at him but didn’t even notice when his camera went up. He didn’t want to impose himself on the scene because he didn’t want people to change their behavior.”

Growing up on the South Side of Chicago during the 1950s and 60s, Pagnano understood the rules of the street, and took great care to treat those he encountered with courtesy and respect. As a second-generation Italian-American growing up in a multigenerational home, Pagnano’s worldview was shaped by working-class values. Guided by his love of family and community, Pagnano sought out his purpose, searching for a way to inspire, support, and uplift the beauty and dignity of everyday people. Pagnano fell into photography by chance, and once the connection was made, the die was cast.

In February 1974, Pagnano and his new wife Kari arrived in Times Square for their honeymoon and immediately began to look for a place to live so that he could pursue his dream of becoming a professional photographer. Working freelance for magazines like Financial World and Business Week gave him the time he needed to pursue his personal work, amassing a singular archive that has yet to receive its proper due.

But all that is beginning to change with the publication of Empire Roller Disco and the newly established Patrick D Pagnano Photographic Archive at the Briscoe Centre for American History, University of Texas at Austin. Though Pagnano is no longer with us, his legacy lives on in the tenderness and care he brought to the people he photographed. “Pat was a street kid so he never seemed out of his element,” says Kari. “He loved people and the energy. He really got into it.”

Empire Roller Disco by Patrick D Pagnano is published by Anthology Editions and is out on April 4.