A new photo book compiles Issei Suda’s Tokyo street photography from the early 1980s, where reality emerges as an aesthetic – and absurd – phenomenon

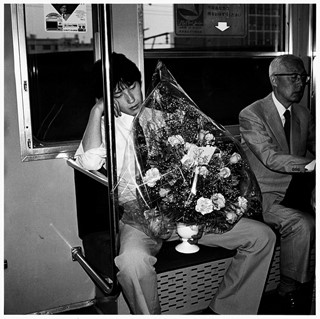

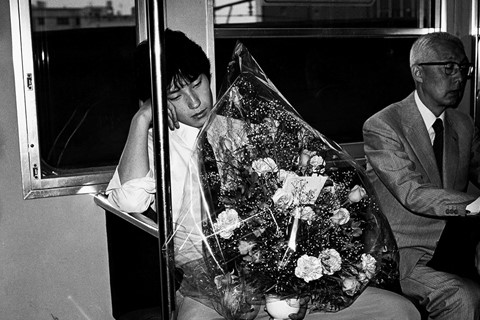

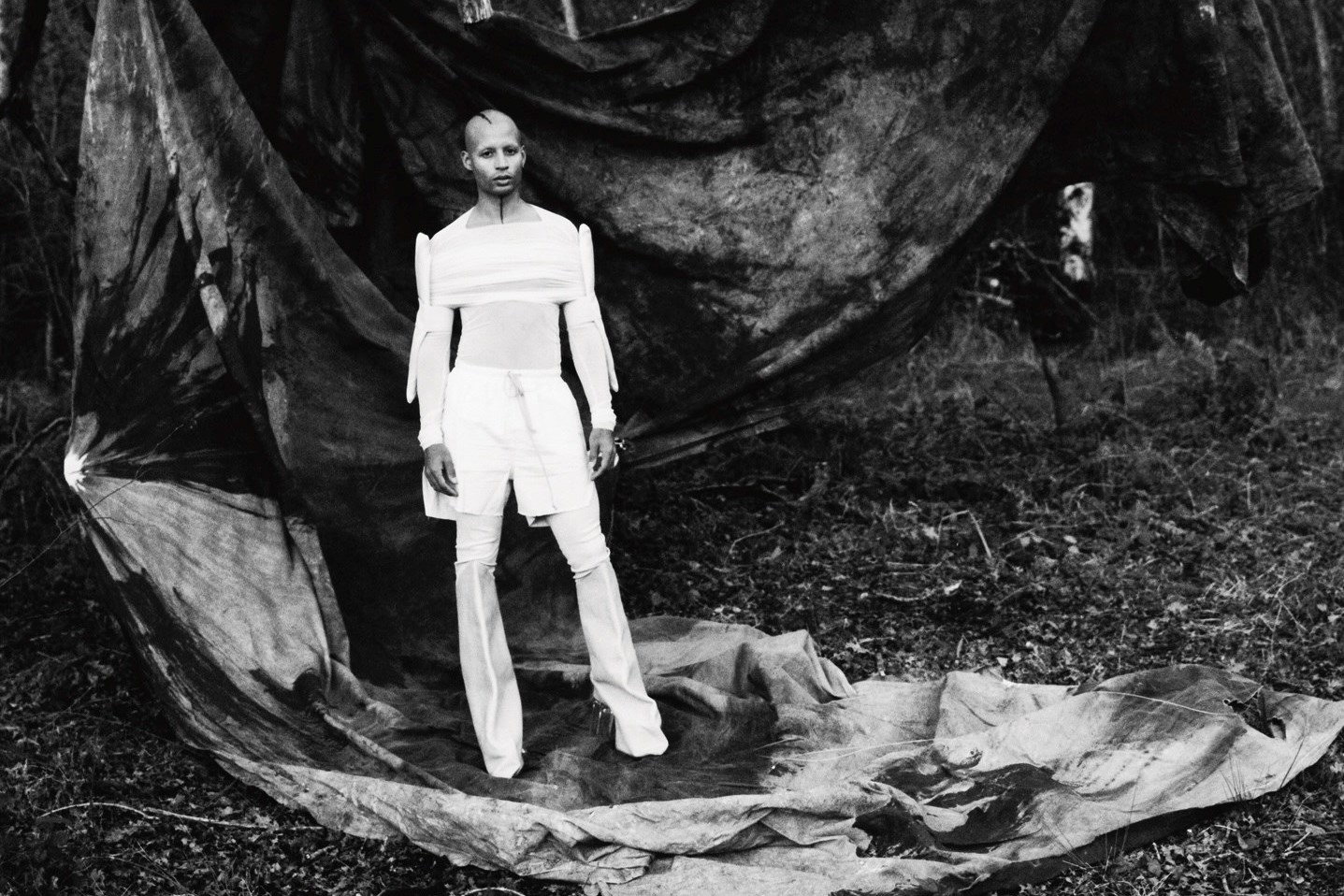

Issei Suda got involved in photography – documenting the underground activities of the avant-garde theatre troupe Tenjō Sajiki – after being entranced by its founder, Shūji Terayama and his soul-searching stories of Mount Osore. However, when he set out on his own path, Suda showed that the most heroic journeys are those close to home. Working in and around Tokyo from the late 1960s onwards, Suda operated much like an ai-kyōgen – the interlude actor of a Noh play who delivers a plot-abbreviating monologue. Through his photography, he produced a highly theatrical oeuvre in which reality emerges as an aesthetic – and absurd – phenomenon.

“Suda took photographs of landscapes, objects and people with equivalent affection,” says publisher Akio Nagasawa, who has contributed much to the widening appreciation of Suda in recent years through a string of stunning books. The latest – which is clothbound and powder-blue – presents, for the first time in its totality, Monogusa Shui, a series that originally surfaced in serial form in the magazine Nippon Camera between 1980 and 1982. “I can feel his sentiments so strongly in this series,” continues Nagasawa. “Through the editing process, I endeavoured to concentrate the readers’ attention on single images. In this way, I hope readers don’t overwhelm themselves in emotion.”

Such a detachment is something Suda also sought himself. In his 1980 article Kongetsu no kuchie – an extract of which is included in this beautiful book – Suda wrote: “My work right now revolves around the idea of capturing both humans and objects based on a perception that avoids emotions such as love/hate or joy/sorrow.” Suda also conceded that his photographs have no great themes, which made brainstorming image titles a “cumbersome” process. “A photograph without a title is, in a way, like a person without a face. In order to avoid that awkward situation, I usually rack my brain to come up with something.”

That the photographs in this book are without titles does not, however, detract from their intrigue. If anything, it emphasises the cool democracy Suda ceaselessly operated through. “What distinguished Suda from the rest was the equal distance with which he approached each subject,” explains Nagasawa. “Suda had a very gentle eye for the scenes he came across within the scope of his own life.” In such scenes, architectural forms appear personified, while human actions and interactions are presented as enigmatic, formalised gestures that recall the rituals of Noh theatre. Suda’s square frames draw us into a parallel world – not Tokyo itself but the shadow it casts, constantly receding into the past.

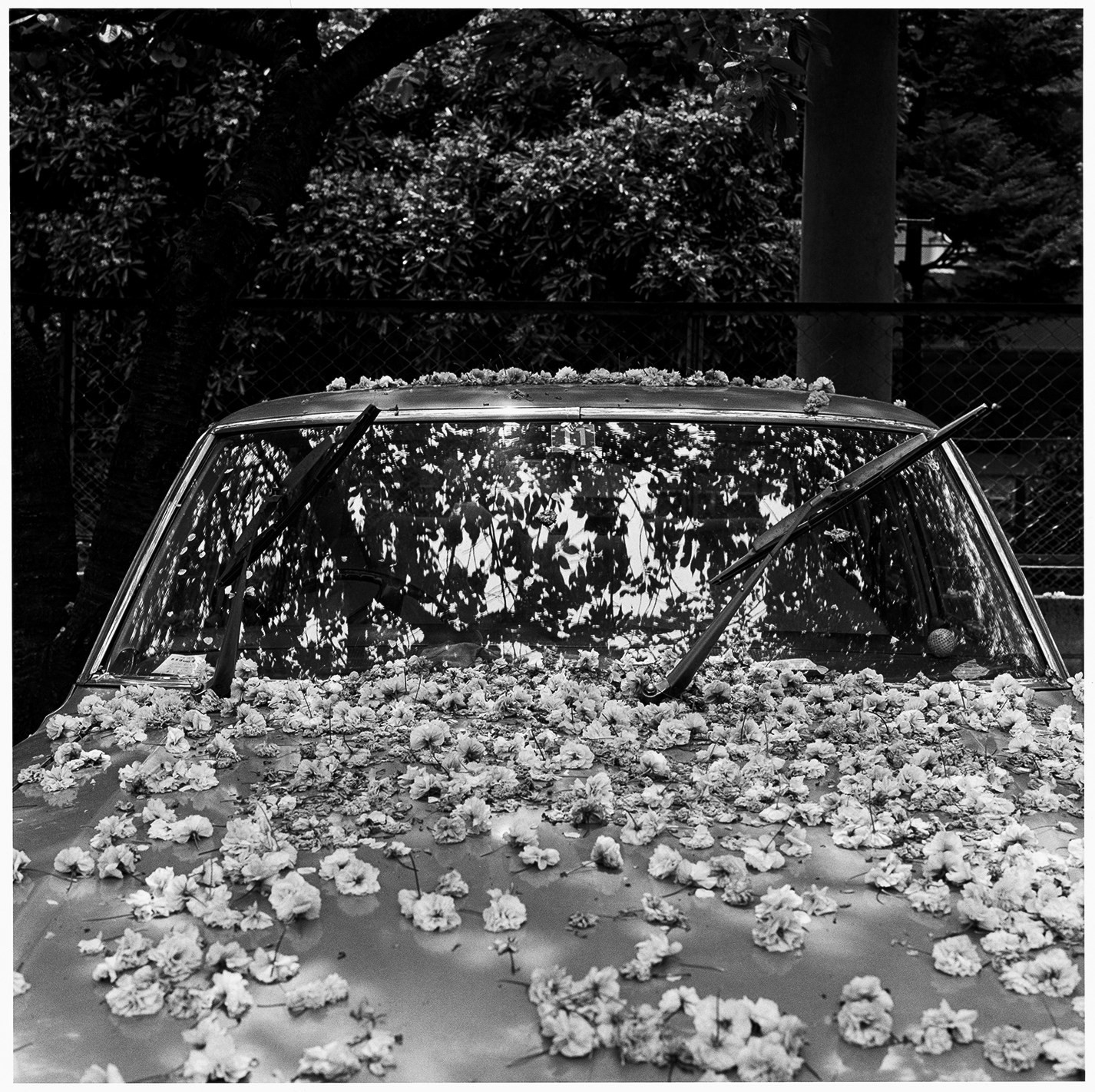

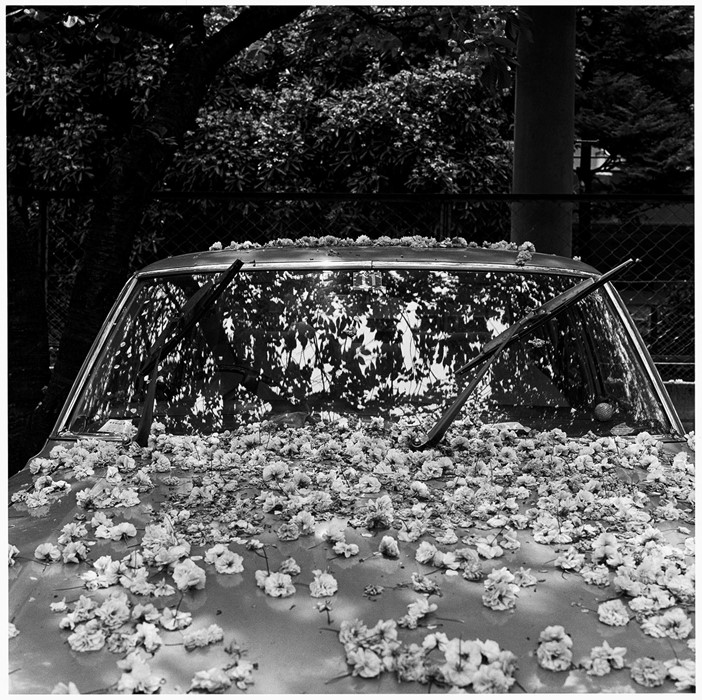

“I would like to try and see what comes out when I just look at things with no contemplation or supposition whatsoever,” wrote Suda. “I will pick up the pieces and make something of them.” That he certainly did. In one beautiful shot, Suda furnishes our gaze on a parked car covered by blossom – its windscreen wipers waggled like eyebrows. Here and throughout the book, the photographer refuses to recognise any meaningful distinction between the organic and the artificial. Suda’s work provides a vivid affirmation of Goethe’s famous dictum: “The unnatural, that too is natural.”

Monogusa Shui by Issei Suda is published by Akio Nagasawa Publishing and is out now.