Celebrating Edward Hopper's portraits of America

Edward Hopper was an American artist in at least three ways. He was born there; he painted subject matter that was distinctly from there – the Cape Cod landscape, gentlemen in slacks and fedoras, Midwestern architecture; and he expressed that which was intangible about early twentieth century America with colour and form. “The American quality is obviously there,” writes Wieland Schmied, the author of recently released Edward Hopper: Portraits of America. “The more we try to analyse it, the more elusive it seems to become."

In pursuing the local, Schmied argues that Hopper effected a representation of the universal. He turns to artist and Hopper’s cohort Charles Burchfield for support: “he achieves such a complete verity that you can read into his interpretations of houses and conceptions of New York life any human implications you wish.”

It was Hopper’s belief in the interconnected nature of human relations, that every being was as Schmied describes “bound to his or her place in the world, dependent on it,” which caused him to fix on his surroundings. “The American quality is in a painter,” Hopper declared; he wasn’t able to paint anything else because of who he was and where he was from.

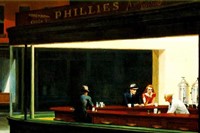

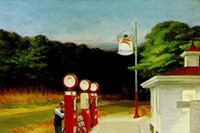

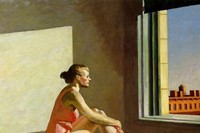

Many of his realist paintings lack human presence. And where people do appear, they are evoked by the brushstrokes rather than depicted in detail. Further, they are dominated by the physical scale of their settings, as the characters in Nighthawks and Gas are. Nevertheless, he approaches them with sensitivity, showing them as contemplative, solitary and authentic. Jo Hopper, the artist’s wife, often modelled for her husband’s paintings. Standing under a light in their apartment, she was transferred pictorially to being an usherette in a cinema auditorium in New York Movie. Sometimes she is part of a troupe with strangers with whom Hopper came into contact and re-used in different roles throughout his works. They are grouped in a huddle; or the individual women are alone in their bedrooms, their bodies caught in a play of light and shadow, undressed and gently erotic as in Morning Sun.

These characters aren’t aware of Hopper’s presence close by, teetering on the threshold. Time Magazine anointed him a “silent witness” to their private thoughts and stilled expectations. We are involved as trespassers also.

But as much as the paintings reveal by exploring private rooms and intimate circumstances, they also suggest that there are many things in the richness of these lives which are clandestine. We can’t see what they can beyond the window; we don’t know why the suitcases are packed and the car is parked outside in Western Motel; we remain outside. In the end the balance created between our feelings of intrusion and exclusion is Hopper’s masterstroke, for we never feel he is taking advantage of his subjects.

Edward Hopper: Portraits of America is out now, published by Prestel.

Text by Agata Belcen