A new exhibition at the Bronx Museum in New York looks at the work of Darrel Ellis, one of the foremost – and under-recognised – artists of the downtown New York art scene

For a brief shining moment, Thomas Ellis had it all: family, community and a bustling photography practice in 1950s New York. Ellis, a former Marine and war veteran turned postal clerk, saw Harlem as the Mecca of Black America. He joined local camera clubs, taking tremendous pride in his work and deeply immersing himself in photographing scenes of daily life uptown and in the South Bronx.

Grounded in the principles of hard word, honesty, respectability and hope, Ellis used photography to uplift the people he encountered, creating a powerful portrait of Black beauty, dignity, and pride during the final years of segregation. He shot far more than he printed, amassing an archive of an era, only to be cut down in his prime. In 1958, Ellis was brutally killed by two white police officers after he double-parked outside his mother’s house.

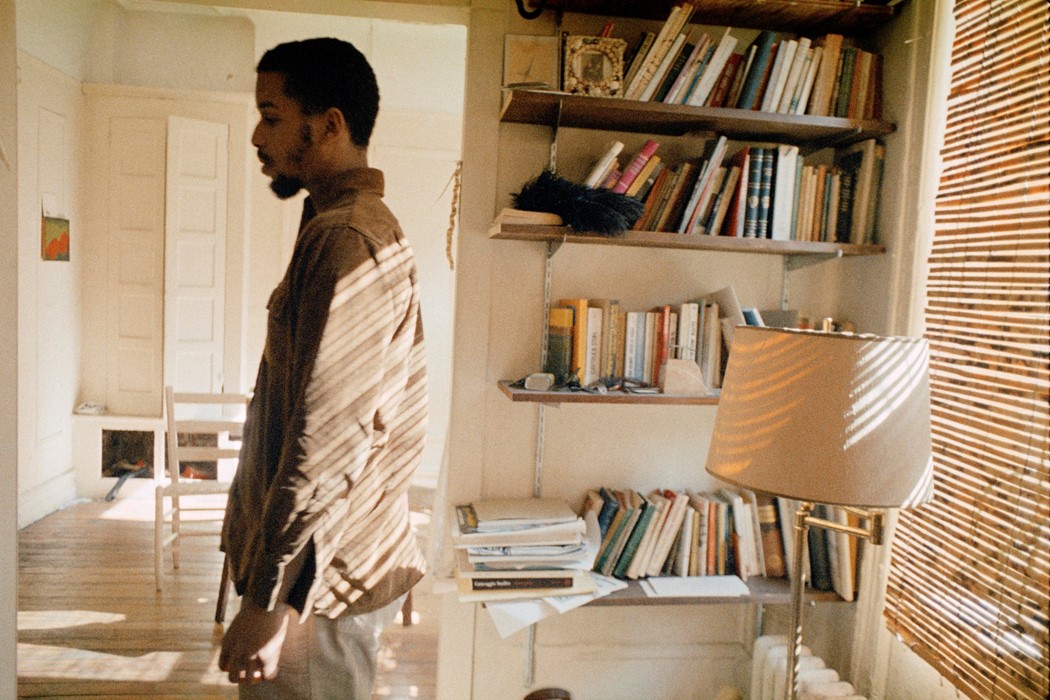

Two months later Ellis’ son, Darrel, was born in the South Bronx. Growing up during the 1960s and 70s, Darrel Ellis lived in a world unlike the one his father chronicled. Set against the backdrop of the civil rights movement, Black power, gay liberation, and New York’s perilous economic collapse, Ellis rejected respectability politics in favour of radical critique.

In 1976, during his senior year at the High School of Fashion Industries, Ellis began keeping a journal, pouring out his aspirations, anxieties, and analyses in both words and images. Over the next 15 years, Ellis kept a series of 52 notebooks that chronicle his journey to become one of the foremost – and under-recognised – artists of the downtown New York art scene. “From very early on, Darrel Ellis realised the difficulty that Black artists had showing their work; he tried to connect with galleries and no one was interested,” says Antonio Sergio Bessa, chief curator emeritus at the Bronx Museum of the Arts, who co-curated the new exhibition, Darrel Ellis: Regeneration.

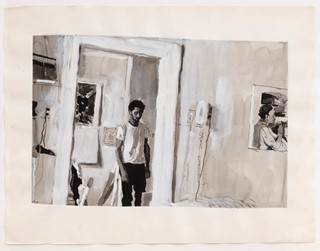

Regeneration brings together over 160 works on paper that considers Ellis’ innovative studio practice in relation to his exploration of Black identity and selfhood. As a young artist growing up in New York, Ellis was both drawn to and alienated by the historically exclusionary canon of art history. Searching for an authentic language to describe the Black American experience within a set of forms prescribed by Eurocentric traditions, Ellis carved out a new space for himself.

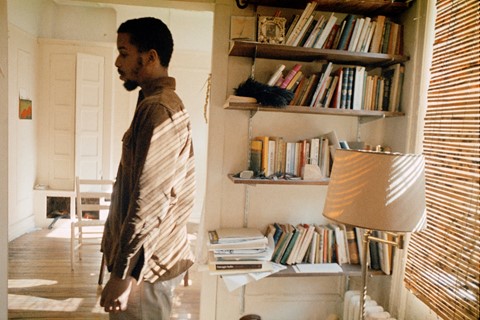

With the Pictures Generation coming into its own during the 1970s, many artists looked to the external world to question and subvert the tired tropes that dominated visual culture, both high and low. Ellis, however, understood the truth lay closer to home. In 1981, Ellis was bequeathed his father’s photography archive, an inheritance that would transform both his practice and his notions of self. Here, in Thomas Ellis’ pictures lay a lost world: a father he never knew, driven to elevate his community through photography.

“We hear from Ellis’ sisters, brothers and notebooks that he was miserable and plagued with self-doubt; his father’s death had really impacted everyone in the family,” says Bessa. “He began going into the archive and began to build drawings, paintings and new photographs, creating a beautiful family portrait just as his father had done. It’s really powerful and brave. I have never seen anything like that. It’s unparalleled.”

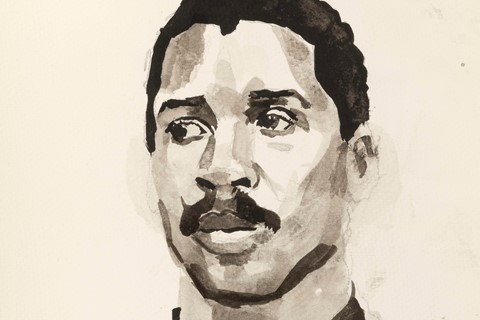

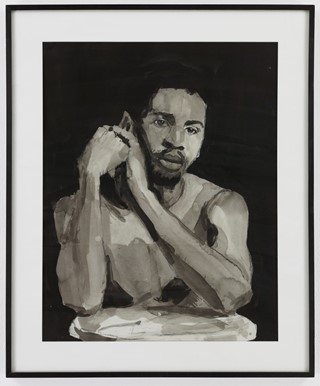

Working across drawing, photography, painting, printmaking, sculpture, and collage, often generating variations on a single image, Ellis reimagined scenes from his father’s life that offered a fleeting glimpse into an unknown world filled with promise and possibility. At the same time, he used the materiality of the image to give physical form to the impact of trauma, absence, love and loss through the suggestion of violence, destruction, decay, distortion, fragmentation and disappearance.

In his son’s hands, Thomas Ellis’ photographs become visual metaphors laden with poignancy and need, while simultaneously portending the harrowing issue of mortality that Darrel would face when he learned he was HIV positive in the late 1980s. He kept the diagnosis to himself, and continued forth, turning the focus of his work to himself.

In 1989, Ellis received an invitation from Nan Goldin to contribute work to Witnesses: Against Our Vanishing, which she was curating for Artists Space. For the exhibition, he returned to two portraits he had sat for in 1980; one by Robert Mapplethorpe, the other by Peter Hujar, both of whom had passed from Aids. Ellis hung their photographs above his paintings from their work, creating an intense dialogue between model and sitter that transcends the spoken word.

For Ellis, images existed in a world of relationships that mirror our own, ever-expanding our ideas of being and becoming, while building bridges across generations. “They’re all different, the photos: they’re like regeneration, regenerated,” Ellis had said. “From one you get many. And that works as a metaphor for the family.”

Darrel Ellis: Regeneration is on show at The Bronx Museum in New York until 10 September 2023.