Co-curated by Wolfgang Tillmans, a new two-part exhibition in Berlin and New York explores the “anthropological” work of the late Colombian artist Juan Pablo Echeverri

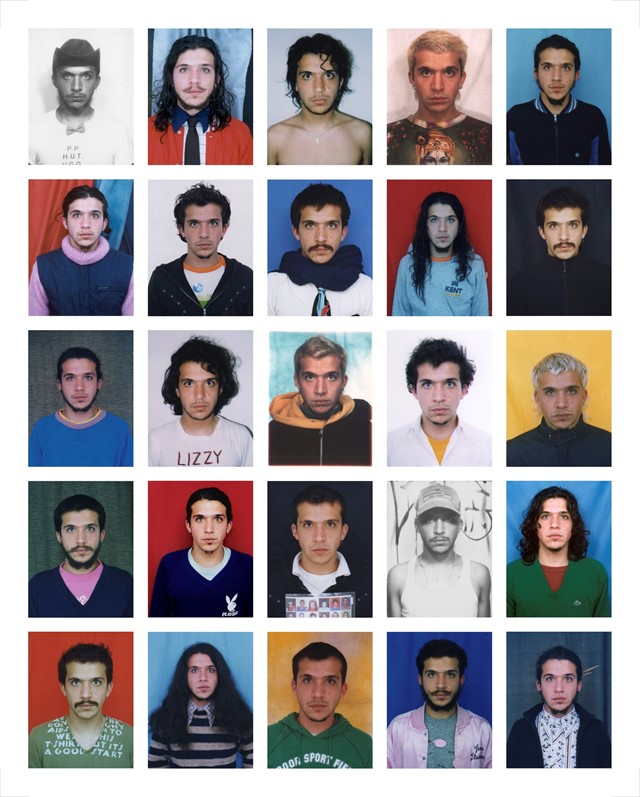

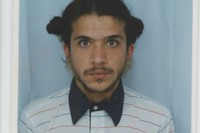

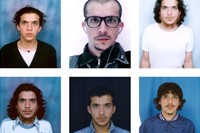

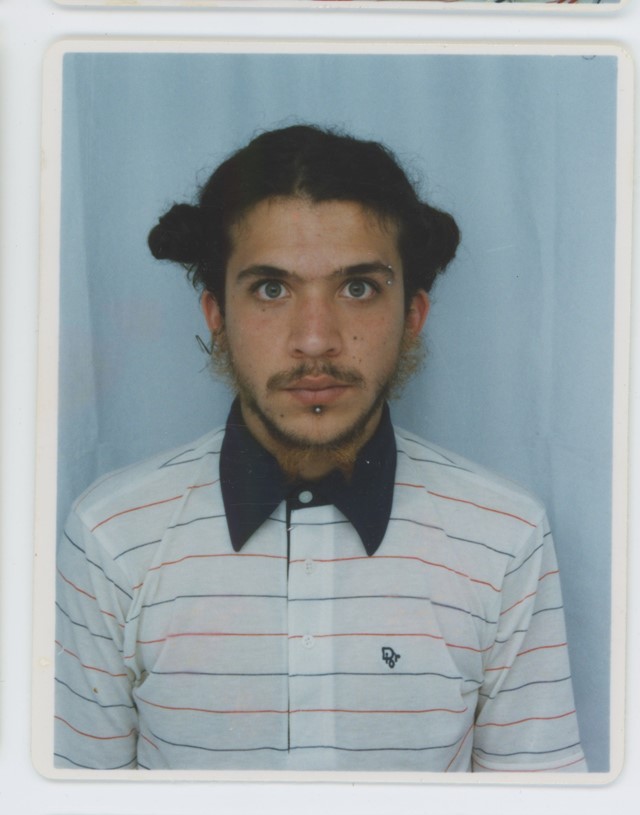

Juan Pablo Echeverri started by piercing his ears, eyebrow and chin. His dark, shoulder-length hair was bleached and dyed red, shaved to the skin then grown out again, into – variously – a crew cut, mullet and frost-tipped mohawk. He trimmed his beard, applied thick eyeliner, and added a baseball cap, or a spiky leather dog collar. Each time the 20-year-old visited a passport photo booth to have his portrait taken he planned his appearance meticulously, careful not to repeat himself. The only constant in the 4x5cm sized photos was his blank, fixed stare.

Every day for the next 22 years, wherever Echeverri was in the world, he continued visiting photo booths and having his portrait taken, collecting them into large, one-metre-long grids, each containing over 400 individual snapshots. This series, named miss fotojapón after the photo-booth company in his hometown of Bogotá, Columbia, eventually ran for more than 8,000 days, recording how he changed his appearance over time. It ended only last year, in June 2022, with Echeverri’s sudden and unexpected death from malaria, at the age of 43.

The anthropologist Marcela Echeverri has been working alongside some of her late brother’s friends and former collaborators, including the photographer Wolfgang Tillmans, to curate a posthumous survey of his work. “I think of Juan Pablo as the anthropologist of the modern world,” she tells me. “He liked observing, analysing and capturing people in our society.” Titled Identidad Perdida, or ‘lost identity’ – a phrase lifted from a note on his studio wall – the exhibition is running in two parts at Between Bridges, Berlin, and the James Fuentes Gallery, New York.

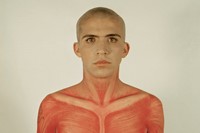

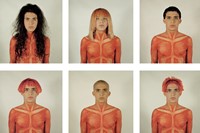

What fascinated Echeverri most was the slipperiness of identity and the superficial means, such as haircuts, by which it can be performed, or – in the case of his photography – subverted. “I envision myself as a medium to let ‘others’ exist,” he once remarked. “I have been fantasising about being ‘anything’ but myself.” MUTILady, for instance, documents a performance from 2003 in which Echeverri was photographed with a series of drastically different hairstyles, beginning with a shaggy mane. “He dyed and cut his hair six times in a single day until he had none left,” Marcela remembers. Like Cindy Sherman, Jo Spence and Claude Cahun before him, Echeverri changed his appearance as a way of exploring the different possibilities of being in the world.

From a young age he had created alter-egos, dressing as a ‘weirdo’ or ‘misfit’ as a form of protection against the homophobic bullying he experienced at his conservative, Catholic all-boys school. With his early home videos, shot in his bedroom in his parents’ house while he was still a teenager, he experimented with role-playing based not on disguise and concealment but rather as a means of queer self-affirmation. In yoSoy R i a l, a video from 2004, he filmed himself lip-synching to Jennifer Lopez’s I’m Real featuring Ja Rule twice over: first, capturing himself dolled up with long hair and lip gloss, and secondly, with a bald head and heavy chain, cussing and mouthing off down the phone in an over-the-top performance of toxic masculinity.

The photographers Nan Goldin, Duane Michals and Diane Arbus were among Echeverri’s influences, but his love of artifice, camp and exaggeration owed as much to trash telly, comic books, drag, social media and, most of all, pop music. His alternative music video for Madonna’s Papa, Don’t Preach, modified to Papi Soy Gay or ‘Daddy, I’m Gay’, was a viral hit in 2010.

Although Echeverri put himself at the centre of his photography, it would be a mistake to interpret it as narcissistic or self-regarding, qualities that are often the target of his satire, particularly when social media is involved. The characters he created in PRES.O.S., a series of 37 portraits from 2017, are based on people he observed on his travels – a hustler, a hairdresser, a drag queen, and a McDonalds server, among others – whom he depicts staring into their smartphone screen, their attributes exaggerated to the point of parody. Other portraits attracted him because of the large amounts of time, labour and guile they required. For Identidad Payasos, a series of diptychs made that year, he persuaded Mexican street clowns to transform him into their look-alikes using brightly-coloured make-up, costumes and wigs, with uncanny results.

Echeverri was a prolific self-portraitist. When he died, he was mid-way through a new photo series depicting rock guitarists, not to mention the miss fotojapón series. “Even though it’s coming up to a year since he passed away, he’s still very present,” his sister tells me. “His work, being self-portraits, means he’s with us all the time.” If he was sceptical of a fixed understanding of identity, the photographs and videos we have left nevertheless give us a clear impression of the man: his wit, his imagination, his sense of humour, and above all his commitment to his art.

Juan Pablo Echeverri: Identidad Perdida runs at Between Bridges in Berlin until July 29 and at James Fuentes Gallery in New York until July 28. The accompanying book is published by James Fuentes Press and is out now.