Through his politically radical paintings, Martin Wong sought to highlight marginalised communities in late 20th-century San Francisco and New York

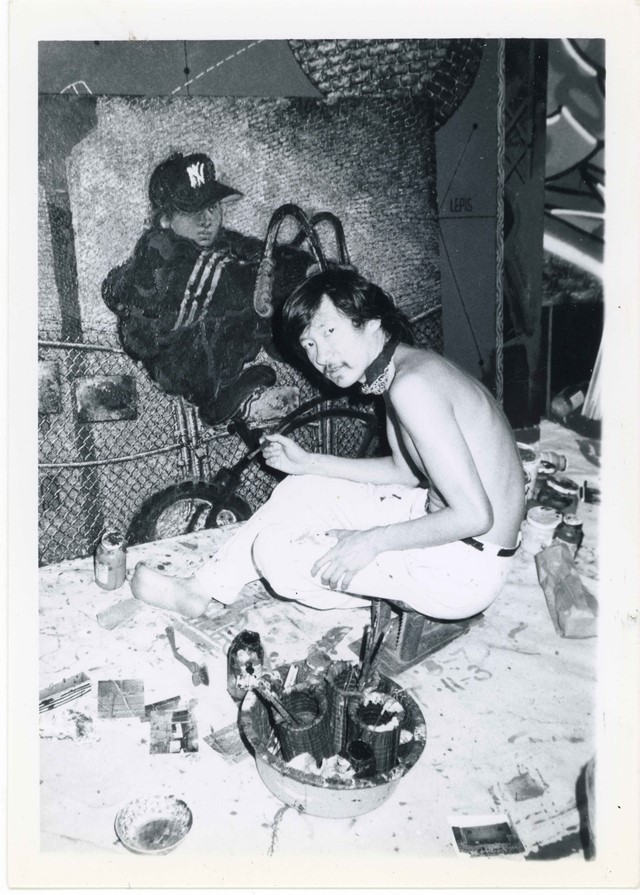

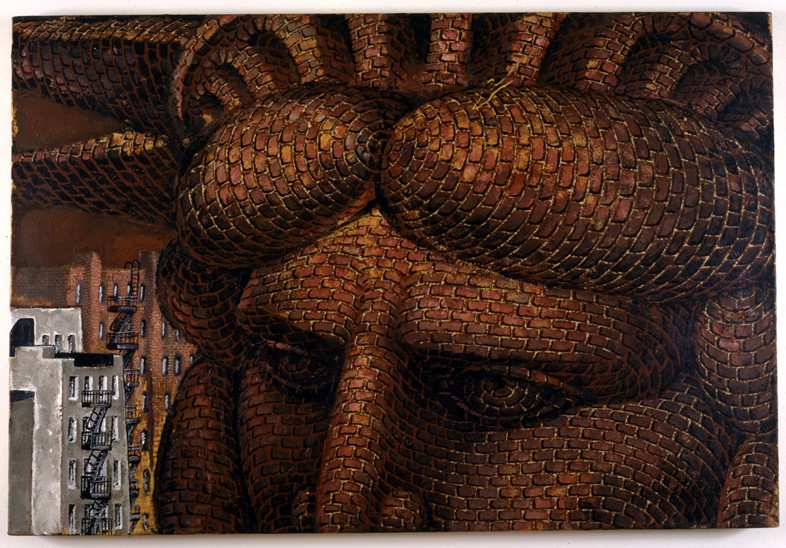

Martin Wong’s paintings remain unbelievably unique to this day. The Chinese-American artist made work during two distinctive cultural eras: 1970s San Francisco and 80s to 90s New York City. His work highlighted those who were subjugated or experienced violence at the hands of the state: one painting features row upon row of prisoners stacked in steely prison beds; another depicts two strapping men kissing in front of a crumbling Manhattan brick block. He designed a distinctive set of hand gestures signing the alphabet, which often featured within his scenes. The surfaces of his works, painted with both hands, have a gritty sandiness to them, as though the soot and dirt of the streets were placed straight onto the canvas.

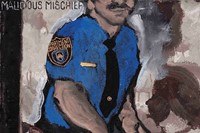

A new show at Camden Art Centre, Malicious Mischief, brings together paintings from throughout his prolific career, displayed against vibrant coloured walls that highlight the playfulness within his politically and socially radical work. “He’s an unbelievable artist,” says Camden Art Centre’s Martin Clark, who has been working on the exhibition for the last four years in collaboration with the show’s curators, Agustin Perez-Rubio and Krist Gruijthuijsen, director of Berlin’s KW Institute, where the exhibition was shown earlier this year. “He was inside that work in the most profound and complete way, both in terms of his own investment but also the paintings themselves. They’re so material, tangible and worked.”

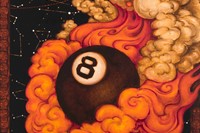

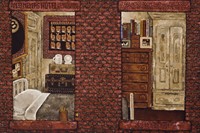

Wong was born to Chinese immigrant parents and grew up in San Francisco. The 60s and 70s hippy movement that was so rich along the West Coast is present in his early work, with psychedelic infusions of colour and kaleidoscopic imagery. His move to New York saw a shift to heavier, darker paintings, with intricately rendered brick walls, vast shuttered storefronts (once forming a long, life-sized installation along Avenue B, some of which is recreated for Malicious Mischief), and references to the city’s burgeoning graffiti scene.

“His work feels incredibly located in its time and place,” says Clark. “When he was in New York, he was part of that Latin American community, but he was also an Asian American man. He never did graffiti, but he collected and loved the work. He was able to be within those communities in a very real way, but also chronicle them and be apart enough.”

While Wong has seen some ongoing success in America, there has been a significant increase in interest over the last couple of years, with works being brought into the public collections of institutions such as MoMA, the Whitney, and the Met. While his paintings speak very specifically about time and place, many of his ideas still resonate today. “A lot of the issues we’re talking about today in terms of identity were really being played out live when Martin was making work, but without the language and structures we use to talk about them now,” says Clark. “Those concerns about how you might find your identity amongst other groups and ideas of otherness are something we’re really talking about now.”

His use of language especially conveys just how nuanced he was as an artist, weaving words and dynamic forms seamlessly together. “When you look at the work across all those years, you might first think it was naïve,” says Clark. “He’s actually incredibly sophisticated. One of the early works is Totem and Taboo, named after a classic Freud book. He was so aware of how the psyche is constructed in language. He understood that sign, signifier and signal were all bound up. That also connects with graffiti and how you have coded language for people who are marginalised. There’s this idea of language revealing but also concealing in a way that only certain groups can understand and use to communicate.”

Wong died in 1999 of an Aids-related illness and moved back to his parent’s home in San Francisco for his final years. His later work and private letters between the artist and friends chronicle the tragic epidemic that he experienced. A painting completed in hospital on the day of his death is shown in the exhibition, emblazoned with the words “Did I ever have a chance?” A montage of video footage in Malicious Mischief sensitively takes the viewer from the streets and restaurants of Chinatown to his cluttered New York studio and finally to his family home. Throughout, the film paints a picture of a man bubbling with creative energy, driven to highlight the injustices of the world around him while also revelling in the joy and full complexity of life.

Malicious Mischief by Martin Wong is on show at Camden Art Centre in London until 17 September 2023.