Published by Loose Joints, Oliver Frank Chanarin’s first solo monograph was conceived as a response to the collective alienation that accompanied Brexit

“Don’t reduce me to tears as a form of control. Don’t allow my allegations to go unrecorded. Don’t assert your authority through sarcasm.” Oliver Frank Chanarin’s first solo monograph opens with eight of these commandments, borne from a set of safeguarding guidelines the photographer transgressed at the outset of what would become A Perfect Sentence (published by Loose Joints, and currently on display at the Museum of Making in Derby, England). “I fell in love with the language of those documents, and when I translated it into the first person those phrases started to feel very emotional, so I used them as a kind of manifesto,” he says. While the early episode saw a group project destroyed and an exhibition cancelled, the experience would shape much of Chanarin’s future book.

Imagined initially as a response to the collective alienation that accompanied Brexit – and similarly informed by the dissolution of his 20-year creative partnership with the artist Adam Broomberg – A Perfect Sentence was to be a return to old practices for Chanarin, and an opportunity to explore the freedom that comes with making photographs independently. “When I first started out I was working in this very traditional mode of using a camera as a tool for social engagement, telling stories that were political, social and cultural. After a while, that started to feel uncomfortable,” he tells AnOther, alluding to the partnership. Examining this thinking, their work shifted to becoming more conceptual, while “trying to interrogate what it means to be a witness in the world with the camera.”

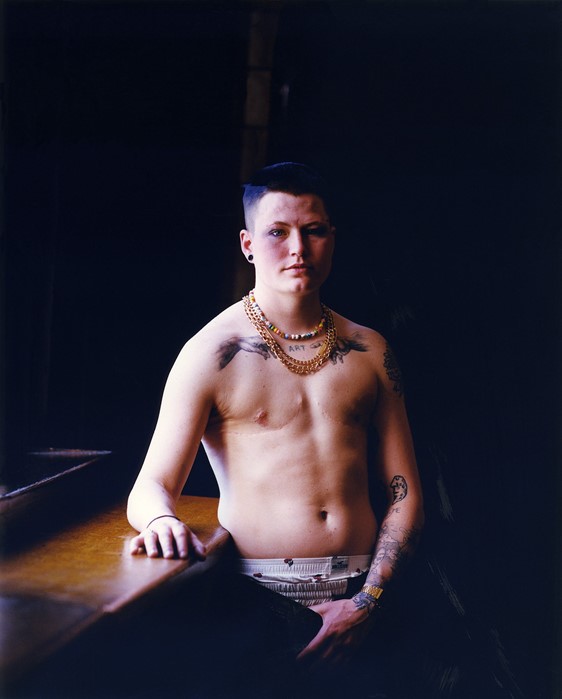

The new project builds on this, marrying classic portraiture with the discourse around ethics and power dynamics, and was inspired by (and ultimately echoes the potential issues of) the work of August Sander: part of the New Objectivity movement, his book Face of our Time, published in 1929, documented professional archetypes across his native Germany in a tumultuous period under the Weimar Republic. “He was a humanist and what he was trying to do was capture the complexity of German society at that moment, but when Hitler came to power, this idea of categorising people started to feel quite uncomfortable, and the work ended up feeling quite problematic,” says Chanarin. Travelling around Britain meeting various communities – drama groups and volunteer zoo staff; sunbathers and activists – in a bid to record the county at this current juncture in time, Chanarin was privy to his own set of challenges, notably the mercurial nature of identity.

Exasperated by a two-year delay due to Covid, Chanarin found the social and political backdrop of 2022 wasn’t conducive to the project he had envisioned, and immediately encountered the public’s anxiety. “Every single interaction felt complicated, it was very confronting,” he says. “The life of images changed so much [in those two years], and the power of social media transformed the way images are distributed and received. Suddenly this idea of me moving through the world on my own turned into a team of people, and that's a very different feeling.” Instead, he would helm a body of work shaped around collaboration, manufactured via the kind of communication that lends itself to fostering a wholly consensual practice: long-term and conversational.

“On the one hand it felt like we were making the picture together – the person in front of the camera had as much control as the person behind the camera – which is a good thing,” remarks the photographer. “But as an artist, making work and kind of authoring what I’m doing, I felt this loss of control that I struggled with.” The final images, with markings and annotations left on many of them, foreground this concept of ownership and control, while elsewhere Chanarin is curious about the notion of consent. The project’s narrative changed several times in the period between his subjects signing release forms and the book and exhibition launching, and the final curation was his own. “That tension is in the work and actually the book is about that. It’s not really about Britain or a photographic survey – it’s a highly subjective interrogation of what it means to take photographs and the power dynamic between me who’s wielding this camera and the person in front of me,” he continues. “Being a photographer is not about taking pictures, it’s about negotiating that interaction.”

A Perfect Sentence by Oliver Frank Chanarin is published by Loose Joints and is out now. An exhibition of the work produced by Forma is on show at the Museum of Making in Derby until 3 September 2023.