A new retrospective in Sussex focuses on Eve Arnold’s pioneering fashion photography and photojournalism that tackled themes of social injustice, civil rights, religion, power, fame and sexuality

For Eve Arnold, her late start in life turned out to be a blessing in disguise, allowing her to experience the fullness of life before committing herself to photography when she was 36. A natural from the outset, Arnold quickly set herself apart in a male-dominated world, becoming the first woman to join Magnum Photos in the 1950s.

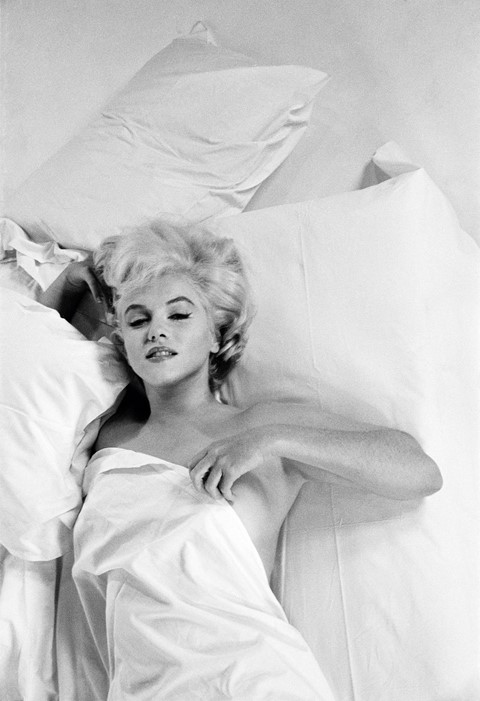

Throughout the course of her storied career, Arnold forged her own path exploring social injustice, civil rights, religion, power, fame, sexuality and birth – issues as much at the heart of the culture wars now as they were then. On July 1, Newlands House Gallery presents To Know About Women: The Photography of Eve Arnold, the artist’s first major UK retrospective in ten years. The show brings together over 90 photographs made over six decades that explore the ways in which Arnold used the camera as a tool of liberation. Whether photographing Hollywood icons Marilyn Monroe, Marlene Dietrich, and Elizabeth Taylor, or documenting the Black Is Beautiful movement of the 60s, Arnold was finely attuned to the transformative power of collaboration.

“Eve Arnold loved human stories and she really cared. She wasn’t ever looking for a cheap thrill,” says Maya Binkin, artistic director of Newlands House Gallery. “She had a lot of empathy, and spent a lot of time researching people and talking to them, really getting to know them. Later on in life, she says that maybe she was naive but she thought she could use photography to hold up a mirror and make change happen.”

Arnold never set out to be a photographer; after her marriage hit the rocks in 1948, shortly after the birth of her only child, Frank. Arnold, then 36, used her newfound freedom and enrolled in a six-week photography course with legendary Harper’s Bazaar art director Alexey Brodovitch at the New School for Social Research in Greenwich Village. In class, assignment number two was a fashion shoot. “She hated fashion photography,” says Binkin. “She found it boring and stagnant but was determined to crack it.”

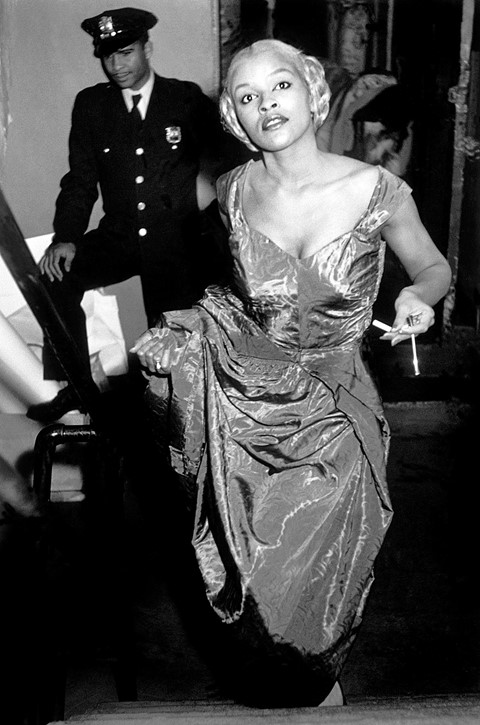

Arnold wisely brought the matter at hand to a trusted source: Nora, her son’s nanny and Harlem resident. She received an invitation to meet top model Charlotte Stribling, more popularly known as ‘Fabulous’, at an upcoming show at a deconsecrated Abyssinian Church. While Arnold felt self-conscious as an amateur stepping into a professional role, she did not quite foresee that her presence as a white woman with a camera was a singular event unto itself. Much like Charles Dickens’ classic, New York’s history can be written as a tale of two cities, with the layered stories of people of colour largely marginalised, misrepresented, stolen or erased. Although Harlem had experienced a literal renaissance during the first half of the 20th century, it remained a world largely unknown by those who never travelled north of 96th Street.

The all-Black audience welcomed Arnold, and joyously cheesed for $40 Rolliecord camera she held in her hands. Not wanting to disrupt the energy in the room, she went backstage and began photographing the model as they prepared to walk the runway. Stribling and the other models playfully collaborated on the shots, creating moments of candour and camp with single aplomb. She later described Stribling as moving “like a golden animal – a leopard, perhaps, or a tiger.”

Arnold returned to class and handed in the prints, where Brodovitch pronounced her work as “completely new and fresh.” He instructed Arnold to return to Harlem and continue the work, a directive she took to heart. Over the next year, Arnold chronicled Harlem’s burgeoning fashion scene, documenting the designers, models and audiences at local church halls, nightclubs, bars and restaurants. She regularly received invitations backstage and into people’s homes, creating a singular archive of the era at a time when Black people were almost wholly excluded from the fashion industry.

After American magazines refused to publish the series, in 1951 Arnold sent her photographs to Picture Post in London, which ran them over an eight-page spread – accompanied by racist screed degrading the women in her photographs. Devastated, Arnold immediately took control of her work to ensure it would never be used to degrade the people she sought to uplift.

That year, Arnold began working with Magnum Photos. With their protection and support, Arnold could ensure the integrity of her work, whether photographing the McCarthy hearings or Nation of Islam rally. “Coming from poverty, she was very interested in how discrimination works and she wanted to photograph the underdog,” says Binkin. “She photographed the underprivileged, the people who were being silenced, and marginalised.”

Arnold understood the power of photography lay in its ability to transform how we see the world. “For years. I have sought a meaning for the term ‘photojournalism.’ What is it?” Arnold wrote in her last book, In Retrospect. Arnold returned to an essay written by art critic Gene Baro for an exhibition catalogue of her work, which affirmed that photojournalism is not a mere illustration of the text, but rather a form of storytelling and recordkeeping in its own right. “If a photographer cares about the people before the lens and is compassionate, much is given,” she said. “It is the photographer, not the camera, that is the instrument.”

To Know About Women: The Photography of Eve Arnold is on show at Newlands House Gallery in Petworth, West Sussex from 1 July 2023 – 7 January 2024.