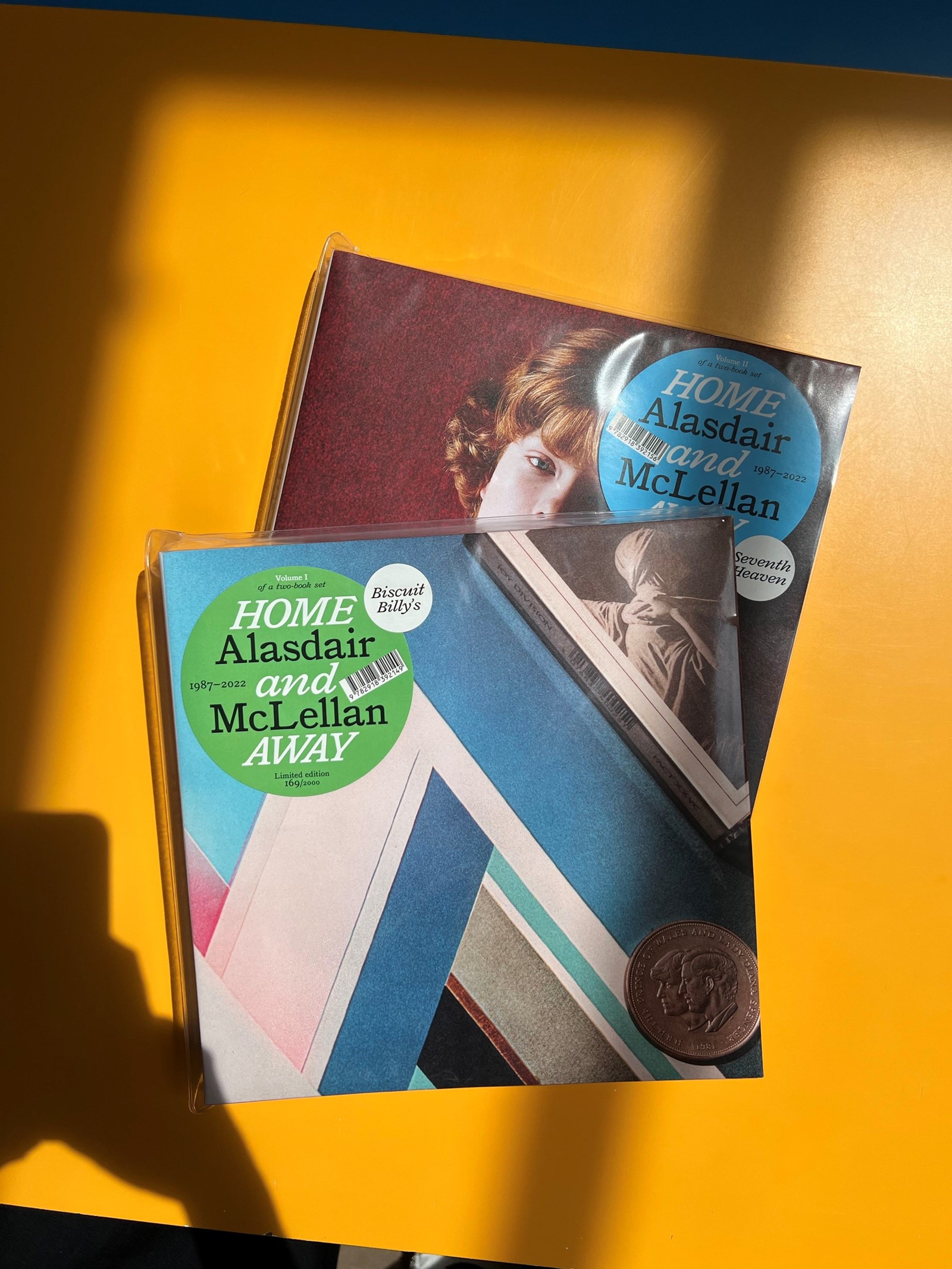

Leafing through Alasdair McLellan’s new book Home and Away, you are confronted with a reality; that McLellan is the premier photographer of British youth culture. It’s sort of inescapable. In two volumes, over 500 images feature from throughout McLellan’s nearly four-decade-long career as a photographer, from portraits – of models, celebrities, his friends and family – to landscapes that capture the sublime beauty of rural and industrial Britain. Then, there are the still lifes, containing records and other cultural artefacts, which hint at McLellan’s formative interests and influences. For as much as this is a portrait of British youth culture, it is, perhaps more, a portrait of the photographer himself; to use a Cilla Black-ism, of who he is and where he’s come from.

Raised in Tickhill, a town near Doncaster on the border between South Yorkshire and Nottinghamshire in England, McLellan took his first proper photograph when he was 13 years old. In this image, we see a boy of around the same age sitting, shoulder high, in a field of emerald-green wheat. The sun illuminates his squinting face, along with the white shirt and orange jacket he’s got on, just about visible through blades of wheat. It’s an image that marks the beginning of this book – but also of McLellan’s career. For though the picture was taken 35 years ago, it bears many of the hallmarks of the photographer’s hand today: youth, and the hope and optimism of that period; a familiarity between the photographer and sitter; and, of course, sunshine – not always a given in Britain, but always one in McLellan’s work.

Of course, Home and Away, which has been designed by M/M (Paris), isn’t McLellan’s first book; previous publications have brought together photographs of young men and landscapes (Ultimate Clothing Company, 2013), the ceremonial troops of the British Army (Ceremony, 2016), the Palace Wayward Boys Club skate crew (The Palace, 2017), skateboarder Blondey McCoy (Blondey 15-21, 2019). But this new publication is his most comprehensive – and most personal – to date. And while he insists it’s not a retrospective, it does feel like his magnum opus – an astounding body of work that demonstrates not only his singular vision, but the expansive world that he has created through his photography, right back to that very first photograph.

Ahead of the book’s London launch, McLellan delves into Home and Away, sharing the stories behind some of his most important images and his advice for the young photographers of today.

Ted Stansfield: How would you classify this book?

Alasdair McLellan: Well, it’s not a retrospective in the sense that it’s about how the pictures I took as a kid are always in my head when I take photos. It’s about their constant presence in [my work]. I feel like it’s a bit too soon [for a retrospective]. And also, I don’t know how I feel about the idea.

TS: The book opens with one of your first ever photos, which you took when you were 13 years old. Can you tell me the story behind that image?

AM: It’s of my mate Daniel sitting in a field. We were walking to a friend’s house and it was quite a long walk. Even though I had taken photos before that, I consciously asked him to pose for this. So even though the picture is so naive – so extremely naive – and even though the quality of the camera was so terrible, it’s just that thing of finding it. Which is why I felt [this book] needed to be done.

TS: And that’s how your photography started – by taking photos of your friends.

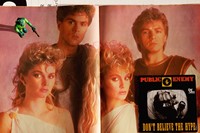

AM: At the time, I was really obsessed with music and magazines, and record sleeves. So I would ask my friends if they would be in pictures like that, but they usually just involved the field behind my mum’s house, or wherever basically.

TS: What music were you into at that time?

AM: I was listening to everything because I used to DJ, which sounds mental now. Me and my friends did this night at a youth club and it was quite popular, and that led to us DJing at various pubs around South Yorkshire in the Doncaster area. And so it was everything from house music to more indie stuff to The Pet Shop Boys to hip-hop, like Public Enemy. It all influenced me in the end. That’s where the idea of the still lifes came from; I feel like when people do still lifes, they’re not that interesting or emotional – I liked the idea of creating something that was beautiful, but also emotional.

TS: Since that time, how do you think your photography has changed and how do you think it has remained the same?

AM: Well, there’s a lot more people [around] now when I take a picture. And I’ve been well versed in hair and make-up, and clothing and fashion at this point. So I guess that’s what’s different. I’ve always been conscious of trying to create a world, even if it’s obviously influenced by certain things, and people, certain music. It’s just more of an educated eye now. But essentially, I feel like it hasn’t really changed; I still feel like the best pictures I approach in the same way as I did when I was young.

“It’s just more of an educated eye now. But essentially, I feel like [my photography] hasn’t really changed; I still feel like the best pictures I approach in the same way as I did when I was young” – Alasdair McLellan

TS: There’s an interesting tension between idealism and realism in your work. How, on the one hand, you present a beautiful, very idealistic version of England, but on the other, you don’t shy away from its realities too.

AM: I’m not consciously trying to be a PR for England because there’s a lot of problems. [Laughs.]. But I do always want to take a beautiful image of something, even if that thing might not necessarily be deemed beautiful. But I guess it depends on what your idea of beauty is – obviously, I find a lot of car parks beautiful. Some people might be like, “Why do you like that car park?” So it just depends. Sometimes it’s just aesthetically nice – if it’s a nicer day, it’s probably nicer to take pictures on that day. Some people might see that as idealistic, but I always think there is something in stuff that isn’t necessarily beautiful. But it’s not meant to feel like an idealistic vision. It’s just meant to be an edit of a vision, I suppose.

TS: How did you make the edit for this book?

AM: We just kept on re-editing and re-editing until it felt right. We were just trying to create a little world and make all the pictures feel like they belong, even if they’re 30 years apart.

TS: Is there anyone you’d like to photograph, who you haven’t yet been able to?

AM: There are loads of people I’d like to photograph. I haven’t photographed Lil Nas X yet and I want to photograph him, because I thought someone like him would never happen: a huge pop star who is very vocal about his sexuality and who is actually visualising it.

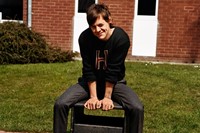

TS: I loved seeing one of my favourite images of yours in the book – one of Harry Styles for Another Man. I think it was the first issue of Another Man I wrote for, so it’s very special to me. What do you remember about that shoot?

AM: I mean, he’s a really lovely person. The reason why I like to take people back to where they’re from is because it gives them enthusiasm towards the project. It’s why I constantly go back to where I’m from. It generates an excitement and an enthusiasm for the pictures, for the photo shoot and for showing a different part of themselves; what they were like before they became this big person. The reason why we sat him on that bin was because he used to sit on that bin during break time or lunchtime. There was a moment when we were taking a picture at Holmes Chapel train station, and one of his old school friends got off the train and [Harry] started talking to him like he’d seen him at school last week. It was quite sweet to watch. Harry was no longer Harry, he was just a schoolmate.

TS: I guess you regress when you go home. So was there a sense of photographing him in his truest form?

AM: Yeah, there is that. It’s sort of a combination of both – there is who he is. But like, it’s nice to take him back. It’s also getting the subject to feel enthusiastic, because obviously, they do a lot of photo shoots. We did the same with Agyness Deyn when she was having a moment in the late 2000s; we took her back to the outskirts of Manchester.

TS: The second book finishes with a photo of a woman looking out into a field. Could you tell me the story behind that image?

AM: Oh, that’s my mum. That’s the field that I took a lot of pictures in when I was growing up. I’ve always liked how it looked. My mum’s been diagnosed with dementia, so I’ve been taking lots of pictures of her and spending time with her – I think she likes having her photo taken, and it’s quite a nice moment. It takes her mind off stuff and it’s nice to do that, to make her feel special. But yeah, I always liked that field and there are lots of pictures of it in the book, through various years and times of year. There are lots of pictures of it from last year and lots from when I was 14, so that’s why I ended on it.

“The reason why I like to take people back to where they’re from is because it gives them enthusiasm towards the project. It’s why I constantly go back to where I’m from” – Alasdair McLellan

TS: Is photographing people an intimate thing for you?

AM: It’s a personal thing. Obviously, I want the person to look their best. There is an intimacy, but it’s also just [about] creating an image that they’re excited by or are interested in. I think it’s nice to make something that’s memorable, not just as a photograph, but even just as an experience. Going back to the Harry and Agyness shoots, it’s just creating nice, lovely memories. We did a similar thing with Alister Mackie, we went back to Grangemouth, the petrochemical plant there. That’s where the title came from, Home and Away. I liked it because obviously, there’s an English thing where you think about home matches versus away matches in football. And then there’s the Australian soap, which I like the idea of because it’s what we watched when we were teenagers. And I guess that’s why it’s like ‘home away’ because of the fact that I’m away; I’m not at home anymore. It just made sense.

TS: I also wanted to ask you about those photographs of the people who are pictured wearing a T-shirt and nothing else. I’m not sure if you’re familiar with the concept of Winnie-the-Poohing, where people wear a T-shirt and nothing else, but wondered if that was what’s going on here? Was Winnie the Pooh a direct inspiration?

AM: That wasn’t the idea. [Laughs.]. It was more about creating a nude that was emotional. That’s why you see those band T-shirts – I didn’t want it to be too erotic. I used band T-shirts as something that had an emotion to them. It wasn’t so much that I was doing the phenomenon of Winnie the Pooh-ing …

TS: What advice do you have for young photographers?

AM: With this book, I wanted to create something that was just about me; where I came from and what my influences were. It’s important that you draw from yourself, from your experiences in life, because you’re the only person who has had those experiences, and that makes you different. So that’s my advice: to look at where you’re from and what’s influenced you, but also the things you like to take photos of, the people who inspire you. They might not necessarily be some big, already famous person – they might just be your friend.

Home and Away by Alasdair McLellan is available for pre-order via M/M (Paris) now. The book will be launching on July 6 at Dover Street Market in London from 6-8pm.