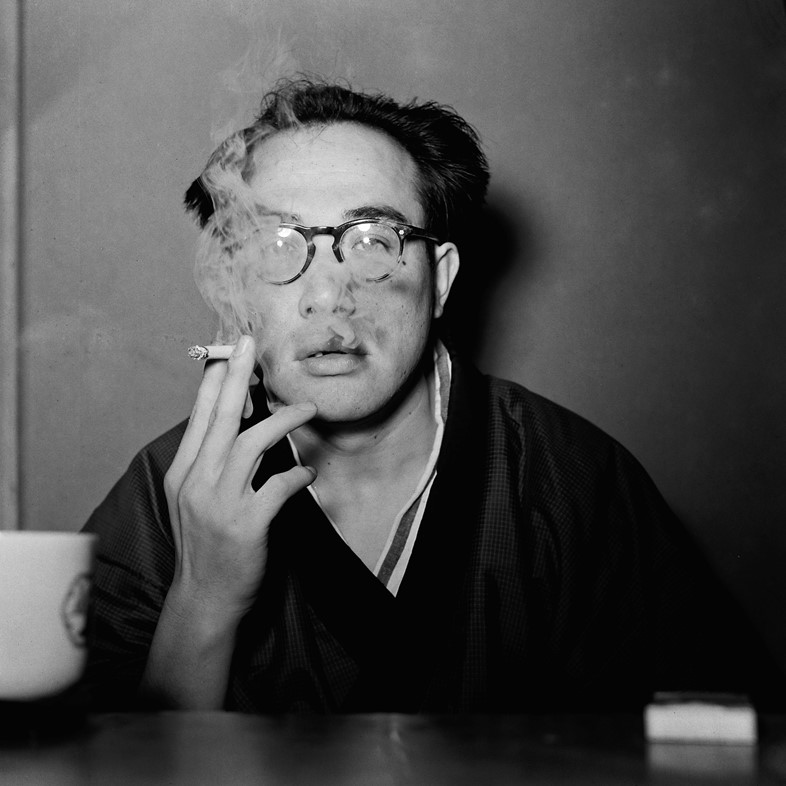

Akimitsu Takagi, one of Japan’s most prolific crime novelists, spent years secretly documenting an art form that has been shrouded by centuries of misconception

The history of Japanese tattooing dates back thousands of years. It gained popularity as an art form in the Edo period (1604-1868), with the rise of intricate and highly symbolic full-body pieces, often inspired by ukiyo-e prints, myth and folklore. Tattooing was popular among people from all walks of life, including artisans, firemen and merchants. But in the late 19th century the craft was forced underground when the government imposed a ban. After 200 years of seclusion, Japan had re-opened its borders, and its leaders were concerned about its national image. The ban lasted 80 years until 1948. That, paired with the craft’s more recent ties to Yakuza gangs, has contributed to a distasteful view of tattooing in Japan’s national psyche.

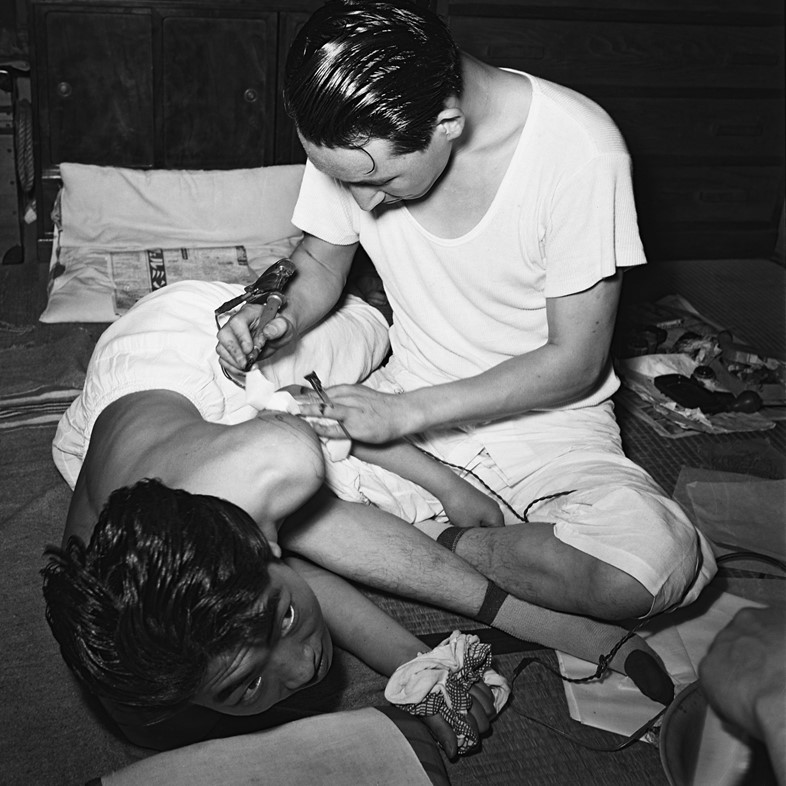

For this reason, photographs of tattooing from the 20th century are incredibly rare; few people had access to artists, and introductions were made only through word of mouth. But, there was one artist who did document it: Akimitsu Takagi, one of Japan’s most prolific crime novelists. He photographed some of the greatest tattoo artists of all time, as well as their customers, but the images remained unseen throughout his life and long after his death. In 2015, Pascal Bagot – a French journalist and expert in Japanese tattoos – discovered the archive, and seven years later he self-published a limited run of The Tattoo Writer. Following a sold-out first edition, a second volume is now available to order. Featuring 130 unseen images, it reveals a story about one man’s obsession with an art form that has been shrouded by centuries of misconception and prohibition.

Takagi’s journey into the world of tattooing was fateful. According to Bagot, he developed an awe for tattoos as a child. He was at a bathhouse with his mother and was struck by the intricate lines of ink that adorned one woman’s back. This image would shape his career many years later but before becoming a novelist, Takagi was a man of science. He studied engineering and worked for an aircraft manufacturer. After the war, he lost his job and sought guidance from a fortune teller who told him to become a writer. This reading, combined with his fascination for tattoos, led to Takagi’s first novel, The Tattoo Murder Case (1948); the story follows a detective as he investigates a series of gruesome murders connected to a secret tattoo society. The book was a huge success, and Takagi went on to author 500 stories – including 80 novels – in his 40-year career.

Pascal Bagot finally got his hands on a French translation of The Tattoo Murder Case almost 70 years after it was first published. As an expert in Japanese tattooing, he noticed the level of detail in its references and was curious about how the author gained such intimate knowledge of the craft. On his next trip to Tokyo, Bagot arranged to visit Takagi’s daughter Akiko, who not only confirmed his passion for tattooing but revealed that he was also a photographer. In her father’s library, gathering dust between piles of books and trinkets, was an album of photographs. Bagot immediately recognised its subjects, who were some of the key players in Tokyo’s underground tattoo scene of the 20th century. “I have a lot of books about Japanese tattooing, and I know all the photos that are available on the subject,” says Bagot. “I knew these photos hadn’t been seen, and that they were remarkable for someone who was not a photographer.”

Japan’s tattoo ban was lifted in 1948, so why didn’t Takagi share these images while he was alive? “I still don’t have the answer,” says Bagot. One theory is that he wanted to protect his subjects from discrimination. Although tattooing is legal, the craft is still demonised in Japan due to its association with the Yakuza. Even though the gangs’ ties to tattooing only date back a century – a small fraction in the greater history of the medium – today, people with tattoos are still banned from entering most pools, gyms and public baths. It is also plausible that Takagi was wary of aligning himself and his family too closely to a subculture deemed as dangerous or distasteful.

These questions will always remain unanswered, but through the photographs, some truths are certain. There must’ve been a level of intimacy that was needed for Takagi to infiltrate these spaces, and the trust that allowed him to exist in there with a camera. “He is one of the important witnesses to the history of tattooing in 20th-century Japan,” says Bagot. The publication of this work invites a renewed engagement with the extraordinary history of Japanese tattooing, and how it continues to shape the development of the medium today.

The Tattoo Writer by Pascal Bagot is out now.