An awe-inspiring exhibition at Hayward Gallery immerses viewers in the Japanese polymath’s big ideas about time and history. “I am trying to reach out,” he says

“I am here, but who am I?” So pondered a young Hiroshi Sugimoto as he caught sight of the sea from the train window on his way back to Tokyo with his family. It might have been the first time he became aware of his self, but the Japanese photographer now thinks in terms of eras and eons, as evidenced by Time Machine, a theatrical and mystifying retrospective at Hayward Gallery. Here, Sugimoto’s famous Seascapes hang side-by-side, all connected by the entire expanse of the sky. Although they capture a single moment in the mortal realm, they also offer a glimpse of the great beyond. One can imagine a young child on the train, peering out of the window and into the void, framing a fading image in his mind’s eye.

“This is how I make photographs,” Sugimoto explains, softly and deliberately. “I never go out in search of something to shoot. I already have a vision in my head and try to paint it with light. For a long time, humans used painting to describe events in history, like Napoleon coursing over the Alps on a white horse. Then came photography, a marvellous invention that people believed would provide evidence of reality. However, photography has actually returned to the painterly tradition. Changeable, the camera is like a time machine, capable of capturing not only a single moment, but history, time and the essence of time itself.”

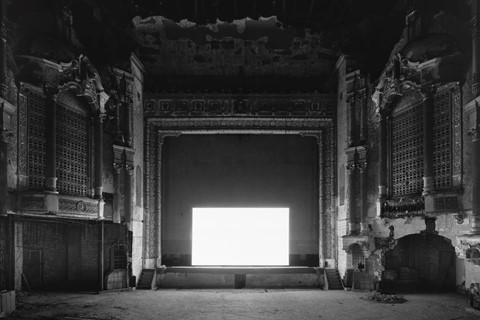

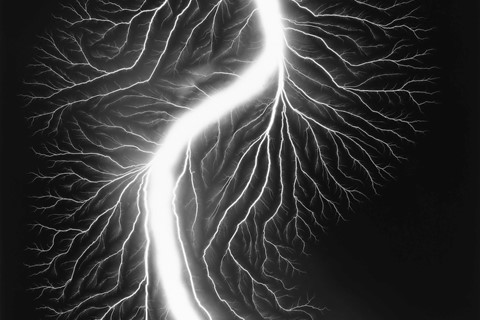

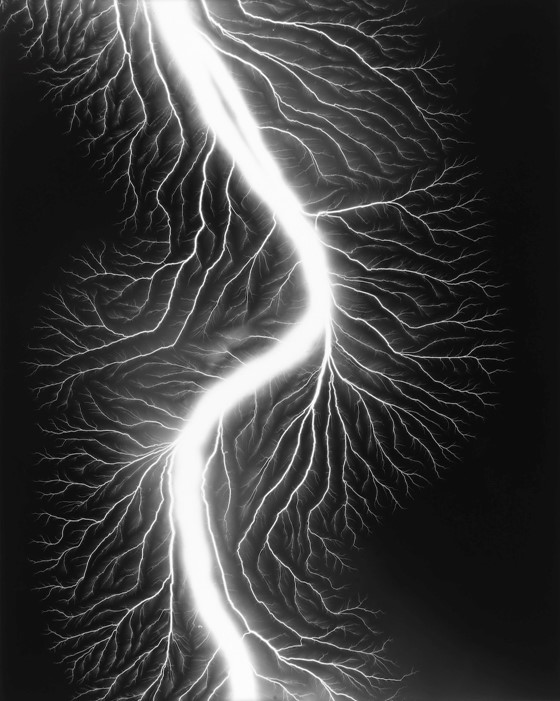

Brimming with the memories of humanity, Time Machine is as mind-bogglingly big in scope as it says on the tin. Throughout ten halls, the exhibition immerses us into Sugimoto’s sea of life, setting him out as a polymath as intrigued by mathematics and physics as by Buddhist philosophy and the traditional Japanese arts that he collects. “I am trying to reach out,” says Sugimoto, whose analogue approaches consistently keep ancient dialogues in play, albeit through a rigorously conceptual process. His Theatres, long exposures that depict entire films into single stills, have more to do with the limits of vision, while his Lightning Fields, imprints of electrical currents that recall some of scientific photography’s earliest experiments, are more about trapping time.

Sugimoto has described himself as an “anachronist” who feels “more at ease in the absent past.” His use of light and shadow has deep Japanese roots, invoking most strongly In Praise of Shadows (1933), Junichiro Tanizaki’s manifesto in which he declared his vehement dislike for the “violent” glare of artificial lighting. But Sugimoto, like Tanizaki, is not advocating for a return to the dark ages, but instead asks us to consider how we, as a modern culture, became so eager to drown out shadows with light. “We have made life easy for ourselves, but what have we lost in turn?” Sugimoto asks. “Before we had electricity, the night was dark. But now, the night is so bright and shiny. It was when I threw open my windows, lit a candle and took out my camera that I discovered each night is unique.”

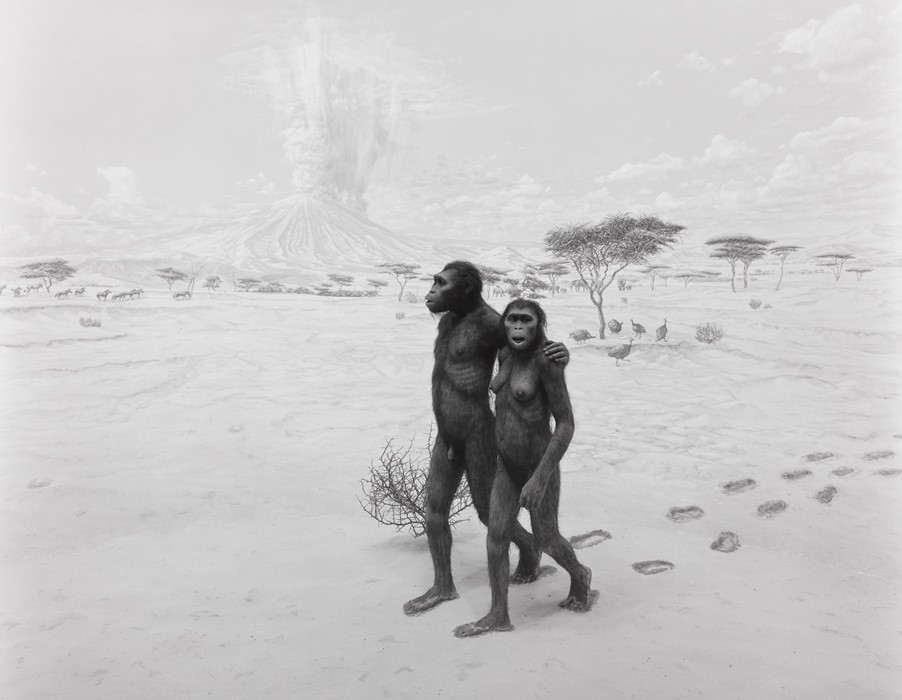

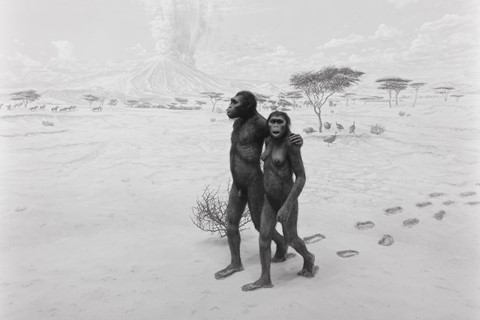

The image of a candle’s flickering flame serves as a metaphor for human mortality and vulnerability. There is a memorial tenor in Sugimoto’s Portraits, which reveal eerily alive, Rembrandt-esque renderings of historical figures, from Anne Boleyn to Oscar Wilde, perched in waxworks museums. Also debunking the assumption that black-and-white photography records truth are his Dioramas. Drawing an implicit connection between the boxed reality of a camera’s viewfinder and the diorama itself, these animal tableaux – like photographs – record vanished life. Since they were introduced into museums in the 19th century, dioramas have been haunted by not only the loss of the preserved animals on display, but also the threatened extinction of their entire species due to the expansion of human civilisation.

“I believe we overpopulated,” asserts Sugimoto. “Civilisation equates to burning down the forest to get energy. If we continue like this, we will lose our planet, and we already are.” In 2014, Sugimoto staged an end-times exhibition at Paris’ Palais de Tokyo, envisioning the worst imaginable tomorrows. He says it was conceived as a “dream story,” but fears how it has become far too prophetic for his liking. “Humans exist in-between the last ice age and the next one. In 5,000 years, what ruins will remain? Perhaps, if any of us are left, we will visit our own ruins, like people visit the Pyramids of Giza today, and think: ‘Wow! Humans were great!’”

The exhibition takes its final bow in the form of Opticks, Sugimoto’s sublime and transcendental photographs of prism-refracted light. They top off an experience which has the familiarity of a great film, for they are as timeless – as infinite – as Sugimoto’s views of the seas and skies. “In Buddhism, emptiness means the open sky,” he says. “Yoko Ono must have passed on some of her Buddhist thoughts to John Lennon as he wrote the line: ‘Imagine there’s no heaven … Above us only sky.’ That is true emptiness. I don’t believe in possession, which is the root of capitalism.” Walking the well-trodden path of the dreamer of images, Sugimoto reminds us that we must look back to move forward. That is, we must speak to the light from the shadows.

Time Machine by Hiroshi Sugimoto is on show at Hayward Gallery in London until 7 January 2024.