In Prem Sahib’s new London exhibition, the atmosphere is eerie, the language is horror, and the subject matter is a climate of neo-fascism and accelerated capitalism

Behind Prem Sahib’s abstract minimalism lies a disconcerting feeling. At his current solo show, The Life Cycle of a Flea, at London’s Phillida Reid gallery, you’re immediately confronted by A Waiting Room (2023), a glass table with the oversized legs of a flea. We get the sense that this menacing creature has become part of the furniture. While many of us might have bed bugs on our minds, Sahib’s flea is more insidious. “I was thinking about [the writer and critic] Mark Fisher,” explains the London-based artist, “and his description of capital as an abstract parasite.”

The flea’s counterpart in the show is the figure of the child. Another sculpture, Scooter Child (2023) shows a child-like figure in a dark, empty hoodie floating atop a micro scooter like an apparition, skinny and disenfranchised, a nod to a climate of austerity. In an adjacent room, a monitor live streams a sculpture of a baby mattress that has been cast in concrete by Sahib and painted with phosphorescence to glow in the dark. It sits on a plinth, almost sacrificially, as it is surveilled. “The figure of the Child has been at the centre of so many moral panics about gender this year,” explains Sahib. “I am definitely thinking about its symbolic stature in that sense, and how those kinds of political arguments converge around this idea of the Child as a fantasy representation of the nation, or ideas around innocence. But also as a symbol of futurity – as something that needs protecting from supposed or imagined threats.” If “the Child’s future has been sold off,” writes the author Sita Balani in the exhibition text for Sahib’s show, “the Flea, on the other hand, has been invited inside.”

Until recently, Sahib’s output has centred largely around themes of sexuality or intimacy and how they intersect with architecture. Take Night Flies (2013), a bent black rubber crash mat, or Alex and Rene (2016), wall sculptures featuring dots of resin hand-applied to anodised aluminium, mimicking the effect of sweat or piss on an industrial surface. “The piss portraits were based on people I’ve met in clubs who are like human urinals,” Sahib explains. “My experiences are often filtered through formal qualities or exist in residual ways, I’m interested in what we leave behind”. Making monuments of the objects and textures he encountered inside sex clubs and saunas have been a way to process the experience of being racialised within them (Sahib is British-Indian) while also celebrating and documenting these ephemeral spaces and communities. It’s not a coincidence that Sahib runs longstanding cult London rave Anal House Meltdown alongside artists Eddie Peake and George Henry Longly. “Like an installation, it’s another form of space making,” he muses, an homage or counterpoint to the queer spaces he’s experienced elsewhere – for better or worse.

The Life Cycle of a Flea is his most overtly political work to date, Sahib distilling the current landscape in Britain; the atmosphere is eerie, the language is horror, and the subject matter is a climate of neo-fascism and accelerated capitalism. Downstairs in the gallery, a life-sized and inverted street light dowses the basement in yellow, a sculpture made of black obsidian on the wall is cracked like a broken iPhone screen, and dried leaves litter the floor. You get the feeling you’re at a crime scene. A sound piece plays UK home secretary Suella Braverman’s voice, a distorted sample from a speech on immigration policy. Her voice is slowed and reversed – an allusion to conspiracy theorists looking for meaning in the reversal of names and words (“Alleus”, the piece’s title, is Suella backwards) as well as a direct reference to the notion of “sending back” immigrant boats. The Life Cycle of a Flea seems to present two ways of looking at things; to the xenophobe, the figure of the flea might be configured as an immigrant and the child a working-class scapegoat for all society’s ills. Or, we might sense a dystopian environment where greed, hatred and fear have seeped into our homes, our public spaces, and our consciousness, leaving our collective future uncertain.

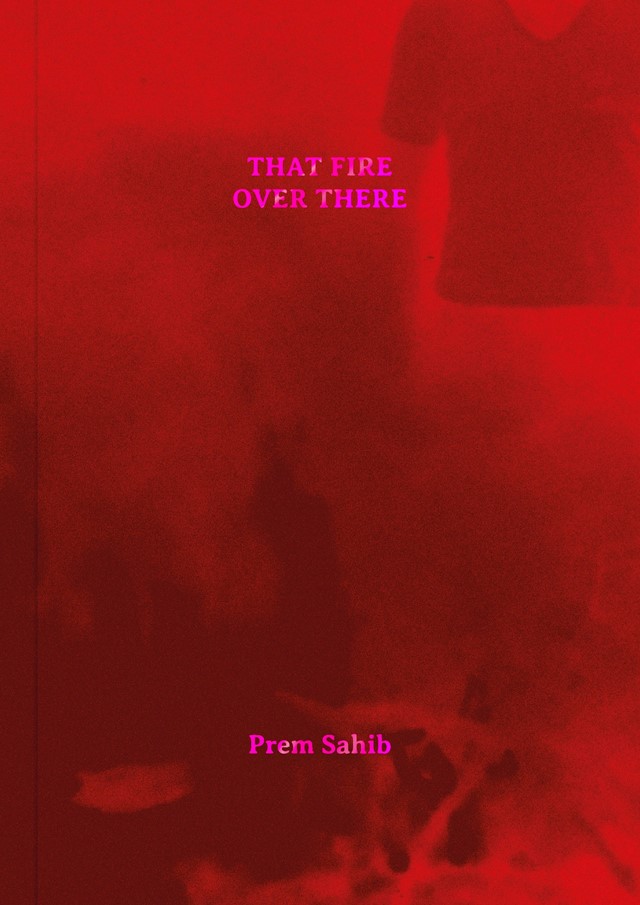

For Sahib, autobiography is always a starting point, but abstracted or twisted to do more conceptual work. His new book That Fire Over There, published with Book Works, however, is more directly personal. The first section looks at cruising through a series of letter exchanges with the artist Ashkan Sepahvand. The second, his family history in west London’s Southall, a South Asian hub with a charged history. The book features archival material from Sahib’s uncle’s career as an activist fighting racist policing and media panics around “South Asian gangs”. The book’s title is a nod to the burning of The Hambrough Tavern, a local pub in Southall that was burned down in 1981 after hosting neo-Nazi bands like Oi! To return to architecture then, “physical vantage points were important to me in mapping out the book,” says Sahib. “I realised that the park where I used to go cruising as a teenager was the same park where my mum told me she slept rough in when she was younger, and where my sister told me she had used a Ouija board to speak to my grandfather. Or the same alleyway where my brother was robbed, was also where my dad was attacked by the National Front. I was struck by how different our experiences of the same place had been, but also how poignant certain public spaces were in our biographies and across generations.”

Towards the end of the book, Sahib presents the transcript of MAN DOG, a sound piece made from a recording with a racially abusive man Sahib met in an online chatroom. Here, the piece is interpreted through an essay by writer and dominatrix Reba Maybury. MAN DOG (2020) is also currently on show at the Gothenburg Biennale alongside Alleus – two diatribes on a feedback loop.

You may also have caught Prem’s work Apotropaic 1 (2023) at Frieze, two empty hoodies much like the one in Scooter Child, one black one red, one leaning on the other’s shoulders, either holding the figure down or perhaps offering a tender or paternal touch, depending on your interpretation. “I like the space that abstraction can offer as a means of creating multiple meanings, or allowing for some level of ambiguity – to avoid being too didactic. I think this elusiveness can also resist certain narratives getting too easily consumed, co-opted, or reduced down. I want my work to operate in this more poetic space – it feels more generative or powerful this way.”

The Life Cycle of a Flea by Prem Sahib is on show at Phillida Reid in London until 8 November 2023. That Fire Over There by Prem Sahib is published by Book Works, and is out now.