The mother of performance art’s uncompromising opera is as dazzling as it is raw

In the final chapter of Marina Abramović’s London autumn triptych (following the opening of her Royal Academy and Southbank takeovers), the artist’s opera 7 Deaths of Maria Callas opened at ENO’s coliseum on Friday evening – the final stop on a European tour, which began in Munich in 2020.

It’s a kind of pop opera – a tour of seven of Maria Callas’ greatest hits, the most memorable arias the soprano performed in roles that became entwined with her own heartbreak-laden life. From Verdi’s La Traviata through Puccini’s Tosca, Verdi’s Otello, Puccini’s Madama Butterfly, Bizet’s Carmen, Donizetti’s Lucia di Lammermoor to Bellini’s Norma, Callas’ most beloved and (seemingly always) doomed heroines are resurrected nightly on both stage and screen simultaneously until November 11.

The evening’s arc is drawn under an impeccably simple, and therefore very gratifying, conceit – even for non-opera fans (possibly more so – it’s been suggested). Each song is performed in its original language by a world-renowned opera singer, in Callas’ bel canto style. Dressed as maids they join Abramović on stage one-by-one, who, in a grand Louis XIV-style bed, plays a sleeping Callas as she dreams a manic medley of those infamous roles. Above, on a vast screen, Abramović and her regular collaborator Willem Dafoe act out a death in a high-stakes, uber-melodramatic short film, complete with costumes by Riccardo Tisci for Burberry.

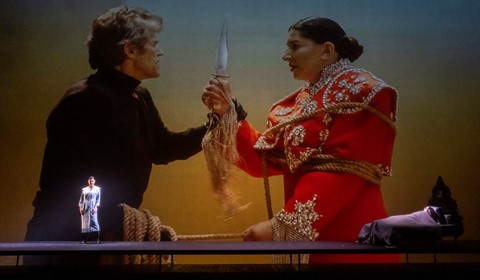

In the Tosca number, Abramović falls in slow motion from the top of the Empire State Building, having carried a lifeless Dafoe through apocalyptic city streets – her gauzy white dress swills about her as she tumbles through the air. In Otello, Dafoe strangles Abramović’s Desdemona with boa constrictors, her red lipstick smearing across her face to the tune of Verdi’s Ave Maria. As Cio-Cio-San in Madama Butterfly, Abramović traverses a toxic Hiroshima-like landscape in a hazmat suit holding her young son’s hand – when her long-disappeared husband resurfaces, she rips open her suit, baring her breasts and dies on the spot amid the scrub. In another, to the tune of the Habanera in Carmen, Abramović plays a bullfighter in a jewel-encrusted bolero who is fatally stabbed by Dafoe as Don José. She also dies of hysteria, jilted, bloody-faced in a wedding dress as the titular Lucia di Lammermoor, and finally walks into the funeral pyre to Casta Diva from Norma – she wears a tux, holding the hand of Dafoe in a golden sequined gown and pencilled Dietrich eyebrows.

You get the picture: the drama is keen as each terrible crescendo follows the last. It’s a cathartic, 65-minute heart attack. Which is fitting, since Callas died of one in her Paris apartment aged 53 – or, perhaps, as Abramović once asserted, of a broken heart. Abramović has been obsessed with the singer since she first heard Callas on the radio when she was 14. She later devoured eight of her biographies and decided, as she once told the New York Times that, “there was so much similarity that I see in myself. We are Sagittarius, the same; we had bad mothers. And then, also, this incredible intensity in the emotions, that she can be fragile, and strong at the same time.”

While meticulously orchestrated and overblown, the films are somehow incredibly raw. Abramović’s every pore is magnified across the silver screen; as she laughs maniacally into a smashed mirror and rubs broken glass across her face her iconic image warps into the grotesque. While her costumes are powerful, so is her flesh. She is corporeal, sometimes heavy-footed – and appears less to be acting or performing than feeling, being – living. As with her artworks, her presence is alchemic. Marina and Maria become endlessly entwined, not least thanks to their shared gleaming black chignons, winged eyeliner and handsome noses. But also in their shared ability to embody the second aria Tosca’s Vissi d’arte (I lived for art), from parallel timelines.

In the opera’s second part, just 25 minutes long (there is no interval in this 90-minute show), Abramović plays Callas in her lusciously decorated Paris bedroom, waking from her tumultuous, deathly dreams. Abramović’s voice casts a meditation, asking Callas to consider her breath, the feeling of her Egyptian cotton sheets, the balls of her feet on the cold parquet as she feels her way around the room. Callas appears to oscillate, unsure, between life and death – just as she does each time one of her records is played. As she recalls the men of her life – composers, impresarios, lovers – who in some way broke her, be that on stage or in real life, she smashes a vase and casts open her shutters before departing into a darkened corridor. The seven maids – the servicewomen to Callas’ legacy in the first half – listlessly clean her room and drape her furniture in black lace before one of them turns on a crackling record that, at last, plays Callas’ ultimately inimitable voice. Abramović reemerges in a gold sequinned gown to dance and glitter in the darkness – an apparition that seems to sing from heaven.

There is something undeniably empowering about the diva – and of course, opera is where the term originated: 19th-century French critic Théophile Gautier first coined the notion to mean a talented soloist in opera, brimming with song, passion and beauty. Kirsty Fairclough, the editor of Diva: Feminism and Fierceness from Pop to Hip-Hop, described divas as existing as “figures to admire, due to the ways in which they amplify self-acceptance, empowerment and celebrate individuality.” Abramović’s opera encapsulates this – living for her art since the 70s, she is uncompromising and such power is deliciously contagious. There are just a few tickets left – book them.

7 Deaths of Maria Callas is on at ENO until 11 November, book here.