As a new exhibition of Valie Export’s work goes on show in London, AnOther offers a brief guide to her boundary-pushing oeuvre

Avant-garde artist Valie Export has been pushing artistic boundaries since the 1960s. Her radical feminist work veers between photography, provocative public performance, and expanded cinema, often questioning the perceived lines between each form. Born in Austria in 1940, the artist was raised by a single mother of three. She studied a mix of design, drawing and painting at the National School for Textile Industry, before pioneering feminist artistic expression through the body in the second half of the 20th century.

While Export has been a mainstay in the art world since then, this year is a particularly big one for her. She is one of four artists nominated for the prestigious Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize, which goes on show tomorrow at the Photographers’ Gallery in London. She also has major solo intuitional shows at C/O Berlin and MAK Center for Art and Architecture at Schindler House in Los Angeles. Like many of her contemporaries, Export’s forward-looking work still has the power to shock and move to this day.

Below, read a five-point guide to the work of Valie Export.

1. Valie Export changed her name to reject patriarchal structures

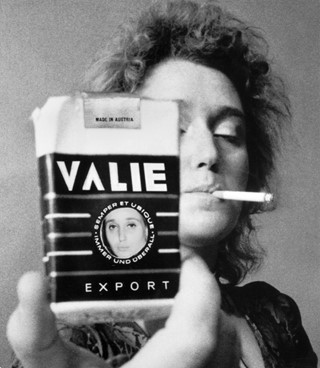

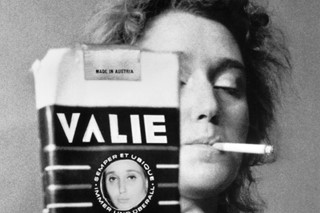

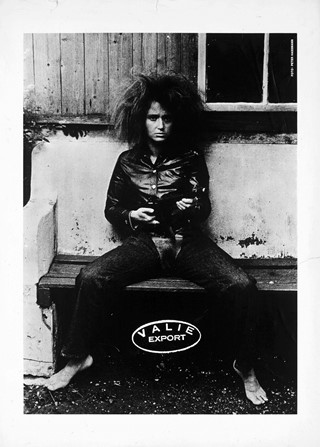

In 1967, the artist formerly known as Waltraud Hollinger changed her name to Valie Export to subvert the patriarchal tradition of women taking their husband’s last names. Her new name reflected both her feminist stance and self-driven identity as an artist. Valie is a play on her given first name, while Export was informed in part by Smart Export cigarettes, which she reimagined for a now iconic self-portrait. Her new last name also highlighted her ambition to reach around the world with her art. “I did not want to have the name of my father [Lehner] any longer, nor that of my former husband Hollinger,” she previously said. “My idea was to export from my ‘outside’ (heraus) and also export, from that port. The cigarette package was from a design and style that I could use, but it was not the inspiration.”

2. She collapsed the boundaries between live performance and cinema

Export has often worked with film and photography in non-traditional ways, using aspects of both mediums in her live performances. In her famous 1968/1986 work Touch and Tap Cinema, she stood in the street with a box strapped around her torso, through which men were invited to feel her breasts. The box featured curtains that the hands went through, mimicking a mini movie theatre and creating a sense of separation from the artist’s face, which stared into the toucher’s eyes, and the sexualised parts of her body. These kinds of works broke down the usual lines between spectator and spectacle, removing the depersonalisation offered by the cinema screen or camera lens.

3. Her early feminist work pushed the limits of bodily endurance

Export often placed her body centre stage. She was one of the first feminist artists to explore bodily endurance in shocking performances. In 1971’s Eros/ion, the artist rolled naked in shards of glass, and then on paper, leaving painterly imprints from her broken skin on the paper. Through such works, she has shown the social and cultural violations that the female body is subjected to, without presenting herself as a victim. “In this case, the shards of glass represent a sacrificial mark, in which the female body is represented as violated, or a violating subject, that does not subordinate itself to the rules of the sociocultural gaze, but demonstrates the concept of the representation of human reality,” she has previously said. “Here, violating means to violate the rules and norms.”

4. She was ahead of her time in exploring the body and technology

In the 21st century, many artists address the inherently combined nature of the human body with technology, responding to a world of rapidly developing AI and machinery. Export began to explore these ideas in the 1970s, with her Body Configurations, a series of works in which she contorted her body around natural and manmade forms, addressing the internal adaptations made in the body to accommodate the surrounding world. “This analogy between scenic and bodily arrangements, these common forms of revealing mood, have served since the beginning of pictorial art as projection surfaces for expression,” she said. She took things a step further with the 1973 work Adjunct Dislocations by presenting her own body as technology-enhanced, with 8mm cameras strapped to her front and back.

5. Export also organises exhibitions and founded the Austrian Filmmakers Cooperative

In the late 1960s, Export became part of the Vienna Institute for Direct Art, putting on a show that highlighted Austria’s feminist art practices. Soon after, she was involved in the founding of the Austrian Filmmakers Cooperative alongside Ernst Schmidt Jr, Kren, Weibel, and Gottfried Schlemmer. The group held screenings in Austria, Germany, Amsterdam and London, highlighting particularly powerful political filmmaking of the year. While she has had her own writing practice about contemporary art, Export has previously highlighted the importance of communicating through other means. “Much of the art of the 1960s, from body art to video and direct performance, was concerned with similar issues. And then there was media art, which made it possible to express things directly, without having to rely on the written word, which was manipulated by men.”

Deutsche Börse Photography Foundation Prize 2024 goes on show at the Photographers’ Gallery in London from 23 February – 2 June 2024.