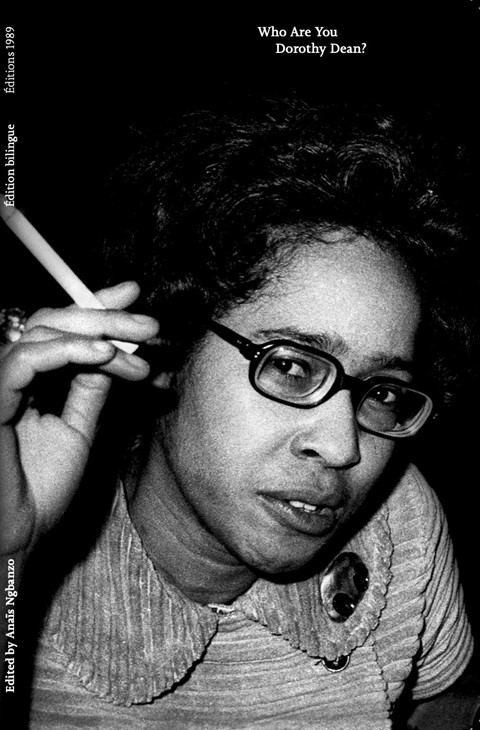

A writer and actress, Dorothy Dean was a mainstay on Warhol’s Factory scene, but in the intervening decades has largely been overshadowed – a new book by Anaïs Ngbanzo seeks to rectify this

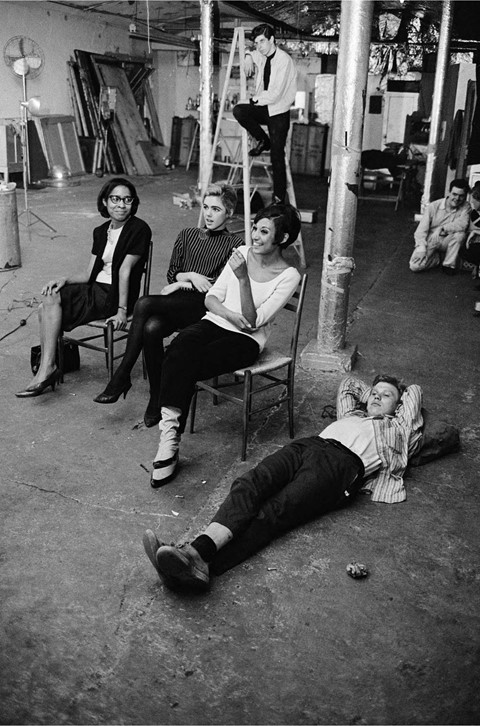

As she details in the foreword to Who Are You Dorothy Dean?, it was a jetlagged bookstore purchase that first introduced Anaïs Ngbanzo to the late writer, actress and socialite’s story. An integral if sidelined figure of Andy Warhol’s New York (she appeared in six of his films, additionally helping to produce several), as an African-American, Harvard-educated woman, Dorothy Dean was a relative anomaly in The Factory environment. “I was very familiar with Warhol’s Factory, reading every poet and exploring the work of most of the prominent artists. That’s why discovering Dean’s life only recently came as a surprise,” explains Ngbanzo, recalling an earlier fandom concerning the city’s underground scenes of the 60s and 70s. “They weren’t very diverse, so I often felt alone in the face of avant-garde movements and scenes where Black figures were overshadowed.”

First published in 1996, in Hilton Als’ The Women, Dean is one of four protagonists whom the esteemed writer and critic pours over, generating portraits that closely observe sexual and racial identity. Acquired on a whim in the summer of 2019, Ngbanzo read Dean’s chapter several times over she says. “What struck me most was her social standing within New York, and how free she allowed herself to be – rare for a Black woman of that time,” she tells AnOther. Nearly five years on, Who Are You Dorothy Dean? is the second book from Ngbanzo’s imprint Éditions 1989, following Gay Guerrilla: L’histoire de Julius Eastman in 2022, about the experimental Black composer. Introducing her first title with a set of performances at Bourse de Commerce featuring Dev Hynes (who also wrote the foreword, and subsequently collaborated with Ngbanzo on a film, A Different Score), in March she will debut as a playwright, staging Dorothy at the ICA in London.

A bilingual title (Ngbanzo was born and remains based in Paris), the new book is the first to celebrate Dean and survey her life and work. Described by Als as “a cynosure in an influential demimonde, a fixture in an era of dramatic social change”, racial politics of the 20th century determined that she remained largely obscured: Who Are You Dorothy Dean? seeks to remedy this. It features essays and photographs, as well as Dean’s personal correspondence with friends such as Harvey Milk and Edie Sedgwick (the latter, alongside letters to Lisa Robinson and Rene Ricard, is what the play is based on), and her writings from the All-Lavender Cinema Courier, an independent film review bulletin she set up in 1976 (a letter from Fran Lebowitz, handwritten in all caps on Interview magazine headed paper, notes her payment for a subscription, with the closing wishes, “I LOOK FORWARD TO YOUR UPLIFTING COMMENTARY”).

“I didn’t have a fixed format, but I knew I wanted to publish a book about her,” continues Ngbanzo, whose research centered on the 20 boxes of Dean’s archive at the New York University Library. Born in 1932, Dean grew up in White Plains, New York; terrifically intelligent, she received her BA in Philosophy from Radcliffe College and later got a Masters in Fine Art at Harvard, with a stint studying painting in Amsterdam. In Warhol’s orbit, and the wider cultural scene she inhabited for close to three decades – much of it spent befriending white gay men (she herself referred to being a ‘fruit fly’) – she was known for her acerbic wit, heavy drinking and the stories that subsequently transpired. “She floated from job to job, mostly editorial and proofreading at publications such as Vogue,” adds Ngbanzo of her limited professional ambitions. “She’s said to be the first woman ever hired as a fact checker at The New Yorker. I’m careful of how I portray her though, as she didn’t leave a clear legacy of completed work [of her own].”

“In all of the jobs Dorothy performed, she was something of a processor, synthesising a massive amount of artistic and cultural information,” writes Emily Wells in the book’s biography chapter. At her funeral in 1987, friends from the worlds of fashion, art, theatre, publishing and business were welcomed by a striking portrait of her by Robert Mapplethorpe. Their first meeting is narrated by Patti Smith in her memoir Just Kids; Dean, diminutively small, was working as a bouncer at legendary restaurant and nightclub, Max’s Kansas City. For Ngbanzo, who in Dean found a Chelsea girl she could finally identify with, her enduring significance is a matter of visual and cultural representation. “There’s an interesting quote from Als,” she asserts, “he says, ‘It is a measure of Dean’s social importance that Mapplethorpe photographed her at all. She was not a characteristic subject … She did not appear to be fashionable or wealthy or the creator of anything important outside herself’.”