Art historian, curator and writer Alayo Akinkugbe is behind the popular Instagram page A Black History of Art, which highlights overlooked Black artists, sitters, curators and thinkers, past and present. In a new column for AnOthermag.com titled Black Gazes, Akinkugbe examines a spectrum of Black perspectives from across artistic disciplines and throughout art history, asking: how do Black artists see and respond to the world around them?

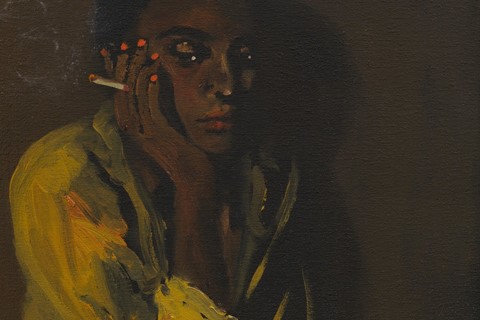

New York-based painter Danielle Mckinney is known for her depictions of Black women at rest within dimly lit, lavish interiors, revelling in their solitude. Taking influence from the lighting of Old Master painters like Caravaggio, Mckinney’s paintings offer a glimpse into the private lives of her imagined figures: dressed in feather-trimmed pyjamas and kimonos, sipping tea from porcelain cups or indulging in cigarettes.

Trained originally as a photographer, Mckinney shifted her practice to focus on painting during lockdown in 2020. Drawing on her experiences of photographing people in public, Mckinney’s paintings elicit a similar sense of candidness, capturing a fleeting moment in time. For her, painting offers more control over the representation of her subjects than photography. Portraying Black women at leisure was not a conscious attempt to fill a gap in representation, but Mckinney also acknowledges, “I [had] never seen Black women resting in paintings.”

In her recently opened solo exhibition, Fly on The Wall at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin, Mckinney presents a new series of paintings alongside familiar works. Below, she talks AnOther through her journey from photography to painting, her love of James Blake and Thom Yorke’s music, and how painting has taught her “internally to let go”.

Alayo Akinkugbe: The title Fly on the Wall mimics the sensation of viewing these paintings; it’s like we’re being let into the intimate lives of the figures. How did you land on this?

Danielle Mckinney: I always think about the audience; I don’t want it to be about a portrait of a person. The fly on the wall represents you [the viewer] in the room with her, watching her, and you’re a part of that moment as well. I want people to be able to enter the paintings as an observer, because the fly in a room is unnoticed, so it’s about being quiet and watching a moment. As a painter, painting them, I was also the fly on the wall. If they noticed me, then it would change the intimacy.

AA: You were trained as a photographer, but in 2020 there was a shift in your practice to painting as your primary medium. Was this influenced by lockdown?

DM: I used to photograph people on the streets and after the lockdown, things changed. People became clammed up and they were much more guarded about their space. The sensitivity of watching someone else became very guarded. I just needed to do something during Covid. I was like, I’m gonna go stir crazy here. The climate of watching and photographing people has changed so much that I don’t think I could ever do the work that I used to do. And New York is not the same place either.

AA: What drew you to painting as a medium?

DM: With photography, I’d have to wait for a moment. It’s like you’re hunting for something to happen. With painting, I go in thinking, “This is what I’m going to paint,” and it never comes out the way I want it. It has a mind of its own, and that has taught me internally to let go. It’s a medium that has challenged me and when I get a painting that I love, I break into tears.

“I feel like I always missed out on seeing classical paintings with Black women. I think, subconsciously, I always wanted to see it. So I was like, ‘Why not paint it?’” – Danielle Mckinney

AA: Do you hope to evoke a sense of nighttime in your paintings?

DM: It’s the evening time where we really feel – in the evening and early morning. When you finish the day and get back into your house, before you grab your phone, you kind of “chillax” –I’m trying to capture that intimacy of that, when we just let go. I call [my figures] my babies and the ladies, and they like to be by themselves. I think it’s just because I’m an only child, I don’t see them with anybody else.

AA: Do you draw on your own personal experiences at all for these scenes?

DM: These women are resting, and I think a big part of me is resting, or wants to show rest. I’ve never seen Black women resting in paintings, so it’s really beautiful. And it’s also so beautiful for people to see them in such a classical city [like Turin], where classical paintings are so dominant. Rest is such a taboo in our culture now and we don’t really know how to stop. So when you see it in art, you can process it a little bit easier and it stays with you.

AA: There’s a sense of luxury in your works – these women are in grand settings, wearing feather-trimmed pyjamas, sipping tea from porcelain cups or smoking idly. Is there a significance to you repeatedly portraying your subjects – Black women at leisure – in this way?

DM: I feel like it’s super important to show it. I didn’t realise it until later but when I was in New York in the art scene, I went to a lot of galleries and never saw Black women, not looking at the work, or doing the painting. I feel like I always missed out on seeing classical paintings with Black women. I think, subconsciously, I always wanted to see it. So I was like, “Why not paint it?”

That’s the beautiful thing that has happened with the work; so many Black women have written [to me] and said “I’ve never seen myself.” It’s gonna make me cry, because you think you’re by yourself with painting. But the beautiful thing is that there are so many people who are thinking the same, and wanting to see the same things as you.

AA: Which artists have influenced your practice the most?

DM: For me, it’s music. I’m very sensitive to music and I listen to it all the time when I paint. I listen to a lot of James Blake. But the [new paintings] were all done with Thom Yorke [playing].

AA: What do you hope that the audience will feel when they encounter this new body of work?

DM: I hope that they can feel what the paintings have helped me to feel, and that’s to be able to stop. The paintings really help us to just pause, and it’s OK to pause. I can get in my own way and be so critical about what I feel or what I’m saying, while the paintings are just [in my studio] taking a nap. And I love that, so I hope it shows people: it ain’t that deep.

Fly on the Wall by Danielle Mckinney is on show at Fondazione Sandretto Re Rebaudengo in Turin until 13 October 2024.