As Art Basel returns to Hong Kong, AnOther speaks to four emerging artists – Sean Steadman, Kara Chin, Steph Huang and Arthur Marie – about their work at the fair

“This year of Art Basel Hong Kong represents a renaissance,” says CEO Noah Horowitz in his welcoming speech. This year, the roving international spectacle has returned to the neon metropolis, making a full return to programming following a lull amid the city’s extended Covid measures. With 242 exhibitors – a 37 per cent increase since last year, making it the largest edition since 2019 – 22 are emerging artists showcased under the ‘Discoveries‘ sector of the fair. These solo presentations offer an exciting opportunity to bring these artist‘s works to the global stage, often for the first time, while still in the early stages of their career.

For emerging artists and up-and-coming galleries, the fair represents far more than great press. Bringing together contemporary and modern art from Asia and beyond, attracting hip art enthusiasts, deep-pocketed collectors and the occasional celeb, the fair buzzes with a sincere dedication to art. Art Basel has helped cement Hong Kong as the capital of the lucrative Asian art scene, where its rapid development in recent years has seen the opening of Tai Kwun Contemporary, the shiny new Hauser & Wirth Space, the mammoth M+ Museum (colloquially nicknamed Hong Kong’s Tate Modern), as well as soon-to-come headquarters from Sotheby’s and Christie’s. If the footfall amongst the brilliant Discoveries sector at ABHK is anything to go by, the area’s market for burgeoning contemporary talent is surely roaring.

Ahead of their showcase at Art Basel Hong Kong, AnOther speaks with four emerging artists debuting for the first time in the Discoveries sector of the fair.

Steph Huang

“My work for [Art Basel] Hong Kong is me trying to understand this mesmerising city,” says the London-based, Taiwanese artist Steph Huang. “I travelled and explored, tried different foods and walked around the city, learning it the old-fashioned way. It’s a colonised city with its own rich culture – and that is there in the booth.”

Before becoming a full-time artist, Huang trained as a chef. “No matter where you go in the world, food is something we can all bond over, and it has such a narrative. I can always remember the restaurants I’ve eaten at, the tastes and flavours, and you definitely feel that in Hong Kong.” Having contemplated the social intricacies surrounding food, Huang’s booth takes the form of an Asian restaurant-cum-marketplace, wallpapered by a pattern of purple decorative tiles, with glass-blown prawns, cherries and references to Asian eateries peppering the space.

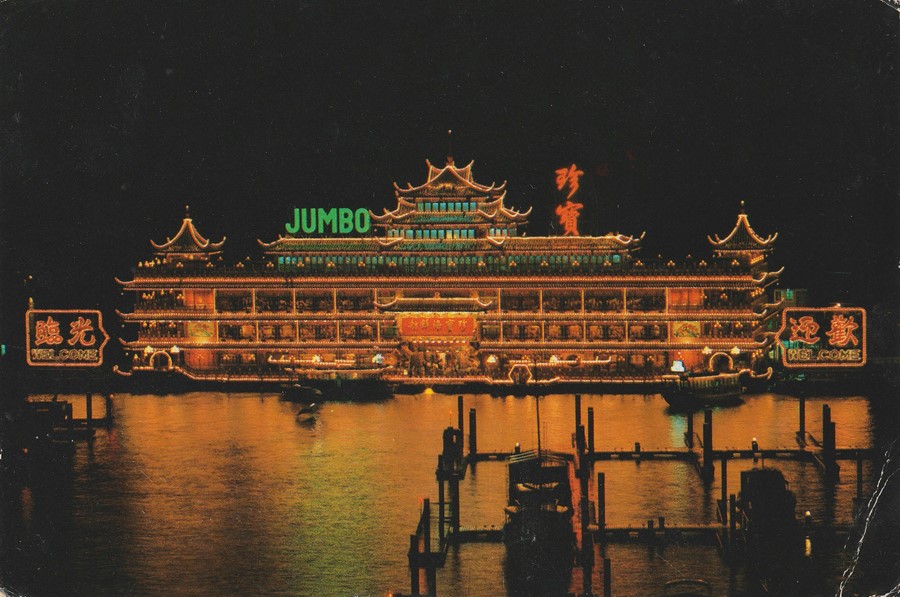

The side of a metal basin brimming with shiny copper fortune cookies reads ‘The Fortune You Seek Is In Another Cookie’, referencing globalised overconsumption and our shared culture’s endless pursuit of wealth. There are enshrined odes to the famed Jumbo Kingdom floating restaurant, which recently capsized after half a century of trade. Elsewhere, a sculpture depicts a winning slot machine with three plump pigs aligned at the centre axis, another reference to greed and indulgence. Loaded with symbols from the food industry that speak to wider issues of colonialism, nationalism and the economy, Huang’s works are a tongue-in-cheek jab at our current climate. “Hong Kong has the city part and the old-town part, which is very traditional. There you see different animals being chopped up and cut, but around the corner, it’s busy businessmen walking around. It’s quite weird.”

Sean Steadman

“The things I say about my work will always be incomplete,” says Sean Steadman. “The art culture we live in is very subject-matter-based. It’s very controlled, it’s very authored, and you can slot that meaning into other norms and concerns. I think that’s phoney, in a way. When people really make work, they’re blind to what they’re doing. They see it the least because they have to make it manifest.”

Rooted in an understanding of both art history and the expansive realms of nature and philosophy, the 34-year-old painter’s works defy the swift consumption of images prevalent in today’s culture, beckoning viewers into a realm where time slows and life’s meanings unfurl. Their nebulous and cosmic forms engulf, teetering dangerously between chaos and order, layered on canvas in forms drawn from centuries of painterly technique. “If we look at an advertising image, one thing beams in. It’s direct,” he says. “The whole point of painting is to be slow. Let’s say you live with [my] painting, some people have said, ‘I see something new in it every day.’ If this is the case, I’ve done it right.”

For Steadman’s first solo booth at Art Basel, and his first time showing in Asia, the artist is presenting a new self-referential body of work. The thread – the heart motif – emerges from his subconscious, as opposed to a purposeful narrative. “You draw quicker than your brain can process, you’re almost watching yourself draw,” he says. For this reason, a sketch becomes his starting point. “In that preliminary moment, you’re almost planting seeds.” He then pads his initial sketch with various other drawings, trying multiple combinations until an idea tempts itself out, which is finished with layers of rich colour. “When I finish, there’s so much embedded information. I’m interested in the idea of complexity,” he says. “If you’re going to make paintings like I make them, you have to saturate them with attention.”

Arthur Marie

In a fog of pallid, greyish tones, French artist Arthur Marie’s booth with Paris’ Fitzpatrick Gallery consists of 21 oil paint portraits of one unidentified figure against a stark backdrop. “It’s 21 portraits, but I do not see them as individual paintings. I see this series as affirmations, hypotheses, prototypes, question marks.” The series’ starting point stemmed from a desire to portray a figure in the liminal spaces between young and old, beautiful and ugly, healthy and ill. In some paintings, their hairlines recede, small scars appear, their features are blanched away into a ghostly abyss.

Rejecting the idea of a portrait as a static representation, Marie delves into the nuances of intention through multiple variations, treating each image as an industrial prototype or psychological manifestation. The textured surfaces of Marie’s portraits, layered to mimic the irregularities of human skin, play with deception, fragility and the grotesque. “In France when you share any advertisements, you must declare when it has a filter,” he says, “but I think it’s a false statement to say that we’re changing our portraits more now than ever before. Old portraits are so cartoonish, and so far away from the sitter. Portraits of great kings are painted powerfully, as a ‘flex’. I question this with my work.”

Kara Chin

British-Singaporian artist Kara Chin initially studied painting at Slade in London, before she realised she had far too many ideas to dedicate her practice exclusively to canvas. She moved on to sculpture in her third year, where she began to execute works across animation, ceramics and installation, each medium beckoning to life her fantastical hybrid creatures with a playful sense of immersion. “I’m very haphazard in the way I make in the studio,” she shrugs. “I’ll start doing one thing, then get distracted by something else. I’ll always be working on several things at once.”

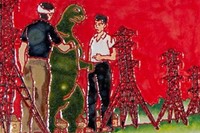

Chin’s first show at Art Basel follows a previous show at Goldsmiths called Concerned Dogs. At the time of speaking, one week before her debut to the public in Hong Kong, she’s just completed nine new works which will be presented among two pieces from her previous show. Titled Shh the Film Is Starting, Chin plucks inspiration from the recurring tropes in the cinematic storytelling of disaster films. These are imbued with a sense of unease that comes with standing up at the cinema, and finding yourself trapped between the audience and the on-screen projection. “It’s that deer-in-headlights moment. It’s that anxiety and dread.”

Chin’s red-carpeted booth contains two miniature yet brilliantly detailed cinema auditorium dioramas (”I love that you become a Godzilla figure walking amongst these models of cinemas,” she says), which are decked out with discarded vapes, popcorn boxes, soy-sauce snappers and plenty of gum. Newer pieces deck the walls, featuring recurring motifs of flocking birds and “concerned dogs”, thanks to their ubiquity in apocalyptic films. “It’s about presenting cinema and franchise films as these myths, almost like biblical texts, the same way Bible stories or folktales are passed down through generations, and repeated and repeated. I was thinking about how these repeated motifs have been rehashed.”

Art Basel Hong Kong is open to the public from 28-30 March 2024.