Published by Loose Joints, Rahim Fortune’s latest photography book Hardtack is a thoughtful meditation of ideas around keeping one’s culture and the work of being an American

Photographer Rahim Fortune first encountered the word ‘hardtack’ while spending time with descendants of the Buffalo Soldiers in Austin, Texas. A simple mixture of flour, water and salt, hardtack functioned as a vital source of fuel for soldiers during the American Civil War. For Fortune, the word took on a deeper resonance, symbolising the durability and tenacity of the South’s complex traditions and the people who preserve them.

Hardtack would also become the title of Fortune’s latest monograph. Published by Loose Joints, who collaborated with Fortune on his second book, I can’t stand to see you cry (2021), Hardtack spans ten years of photographic work. About a third of the images were taken on assignment, while the rest are from Fortune’s personal practice.

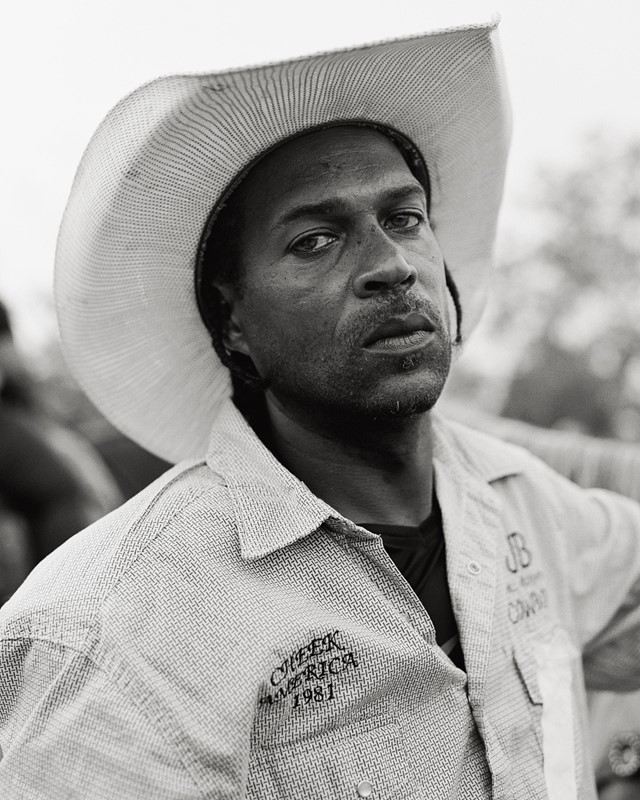

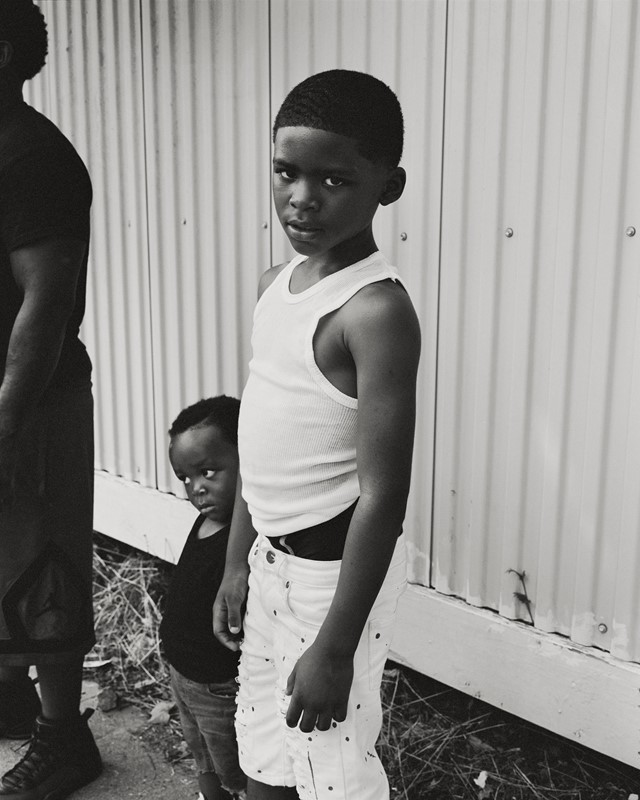

In the South, history never leaves you; it is as ever-present and constant as the weather. A native Texan, Fortune knows this intimacy well. In his images history is never sequestered to the past; it lives and breathes in the hands and faces of the women, men, and children he photographs. It’s in the folded and sharply manicured hands of a grandmother in her Sunday best, the artful curve of the cowboy’s hat and a buckle that reads, proudly, “ASGCA Champion 2002.”

While studying sociology at CUNY, Fortune worked as an assistant to two formidable photographers: Magnum photojournalist Eli Reed – who showed Fortune how photography could be used to “speak on social or personal issues”– and Wayne Lawrence, a member of the legendary Kamoinge Workshop, a collective of Black photographers established in Harlem in 1963. Fortune also cites Houston photographer Earlie Hudnall Jr, the civil rights-era photographer Consuelo Kanaga, and the Farm Security Administration generation of photographers, such as Dorothea Lange and Russell Lee, as key influences.

All of the images in Hardtack are in black and white and most were shot on film. Fortune shoots in 6 x 7 format, a choice that speaks directly to the photographic lineage he sees himself as being part of. He is deeply aware and critical of how photography has been used historically to construct limited narratives about the American South, particularly its Black residents. “I’m trying to use this book as a way of observing the historical relationship between Black Americans and photography,” he says. “Particularly the use of the silver gelatin print, both from our own community photographers, but also from [the] outside.” Since its inception, the photograph has been used as a tool of self-fashioning, for individuals and societies alike. “It’s no mistake that Frederick Douglass and Sojourner Truth were the most photographed people of their time,” Fortune adds. “I think that Black Americans on the heels of slavery understood very quickly the power of photography and the power of making one’s own self-image. I’m very interested in that as its own kind of canon.”

Generation after generation of African American image-makers – from James Van Der Zee to Gordon Parks – have carried on this tradition, and Fortune, thankfully, is one of them. He has that rare combination of the artist and the historian. In one photograph, AME Church Interior, Tucker, Texas, 2022, layers of images speak to a legacy of African American community and autonomy. There’s an undeniable lyricism and grace found in Hardtack, as in Praise Dancers, Edna, Texas, 2020, in which a group of worshippers – their arms spread towards the heavens – look as if they’re about to take flight.

In Hardtack, self-presentation is a form of self-preservation, with clothes pressed, belts cinched, and edges curled. Or, in the case of Queen of Hearts, Atlanta, Georgia, 2019, hair sculpted magically – and majestically – into the shape of a heart. “I became really interested in this idea of self-creation through clothing,” says Fortune. “Especially within the wake of this country’s current political moment. What does it mean for a Black Southern identity?”

History marks the land; and work, too. In many ways, Hardtack is about work, the back-breaking kind: the work of raising a family and of keeping one’s culture. It is the work of being an American; the work of somehow, despite the odds, keeping hope alive.

Hardtack by Rahim Fortune is published by Loose Joints, and is out now.