With her whimsical, larger-than-life food sculptures, Laila Gohar attempts to collapse the gap between art and food. Popular on Instagram for her edible and aesthetically pleasing concoctions – which include towering stacks of cakes, artichoke swans, chairs made out of brioche, and breasts made out of mochi – Gohar is a go-to collaborator for brands including Simone Rocha, Prada, Comme des Garçons and Hermès, and has shown her work in museums around the world (she recently displayed a delicate baby quilt made out of flatbread, painstakingly stitched together, at MoMu in Antwerp alongside work by Louise Bourgeois and AnOther contributor Harley Weir). Born in Egypt, and now based in New York for over a decade, in 2022 she launched Gohar World with her sister Nadia, a tableware brand with a surreal and humorous edge. “The food is never really the point,” says Gohar today, speaking on the impetus behind her socially conscious practice. “My work is about setting the stage for people to be uninhibited, to feel more like children, to break the ice.”

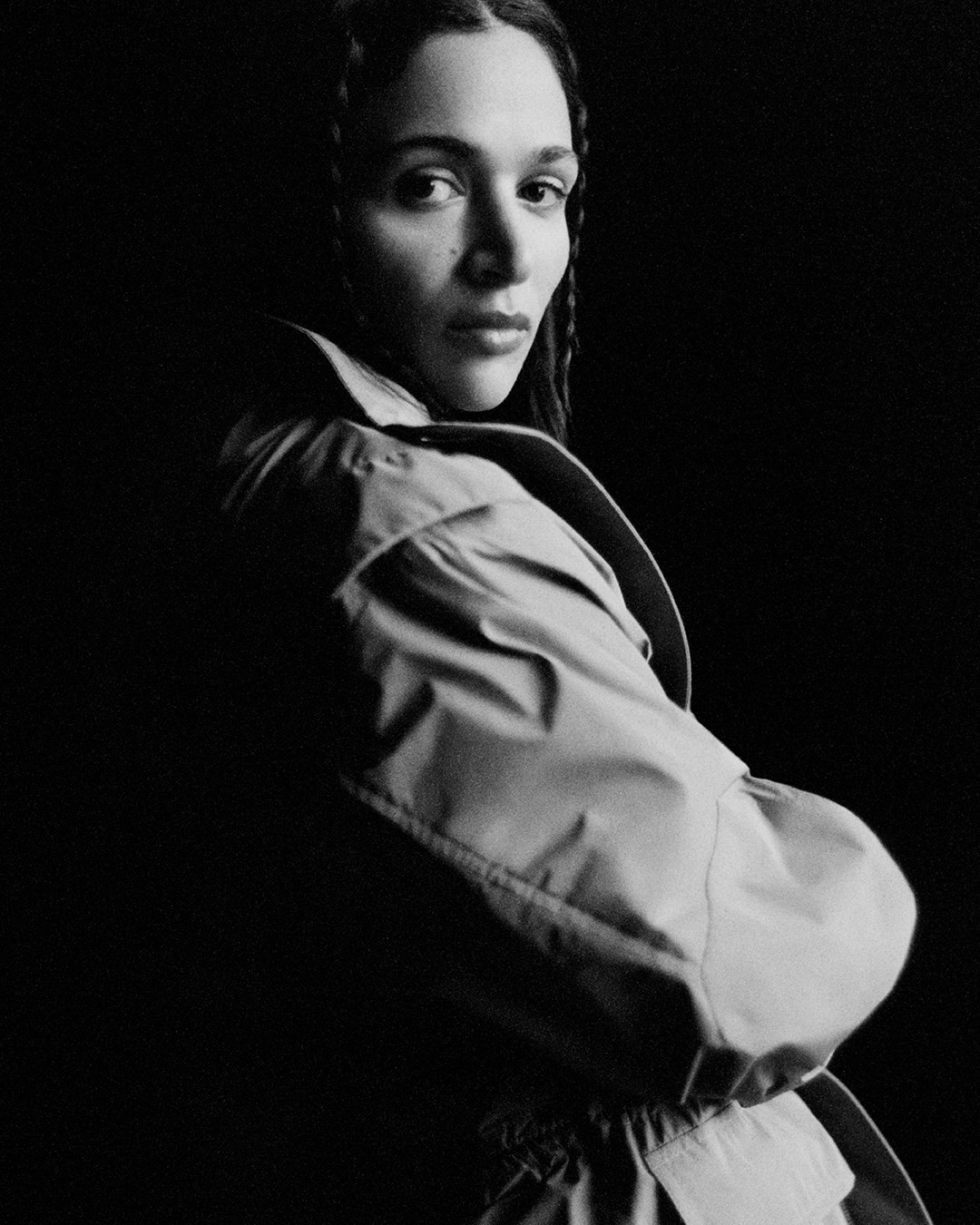

These fantastical elements of Gohar’s work make her the perfect participant for An Invitation To Dream, a new exhibition curated by Jefferson Hack for Moncler at Milan Central Station. The Dazed Media CEO and co-founder has invited some of the most extraordinary minds shaping culture today to inspire us to dream like them, with portraits of Gohar, Daniel Arsham, Deepak Chopra, Isamaya Ffrench, Jeremy O Harris, Francesca Hayward, Julianknxx, Zaya Ribeiro, Ruth Rogers, Rina Sawayama, Sumayya Vally and Remo Ruffini shot by Jack Davison. Coinciding with Milan Design Week, the show marks the first time in history that Milan Central Station has been transformed into a public art space, inviting passersby to ruminate on the power of dreams.

To celebrate the exhibition, Jefferson Hack spoke with Laila Gohar about how she first got into food, the importance of imagination, and her hatred of moodboards.

Jefferson Hack: What was life like for you growing up?

Laila Gohar: I was born in Cairo, Egypt, as one of four children. My parents worked hard and did the best they could, but I always had this extra energy or rage. They described me as a difficult child to raise. It was almost like I had more energy than my little body could contain, and I didn’t know what to do with it, so I would often get in trouble. I was on the sports team and good at sprinting. I remember thinking, ‘These skinny little legs of mine; they’re going to get me out of here.’ Cairo was a nice place to grow up, we had a good life, but I felt like I needed to get as far away as I could and figure things out for myself. I didn’t know exactly where I wanted to go, but it needed to be somewhere I had no connection to anybody.

JH: Did you know you were creative at that point?

LG: I wasn’t able to access it as much when I was a kid. Being creative was almost like an outlet for this burning desire and discomfort I had. I feel like it’s the same for many children: you’re not so good at school, you’re made to feel like you’re dumb because you’re not excelling at the regular school stuff … Even now, I still have a bit of imposter syndrome. I’m very dyslexic. I’m so thankful that I figured out how to channel all of that energy into what I do. If I hadn’t figured out this outlet, bad things could’ve happened.

JH: How did your career start?

LG: I was always interested in food but it wasn’t so much about the culinary arts. My aspirations were not to work at a Michelin-starred restaurant or to own one. It was more about using food as a conduit, or as a spark, and using it in spaces that tend to be less comfortable. Restaurant spaces are meant to be comfortable; they greet you, treat you well, you’re welcomed, your guard is down. But the work I do happens in spaces that are a bit more tense, like galleries or museums. You walk in and you might be a bit uncomfortable.

JH: And you break that tension, right?

LG: That’s exactly the point of my work at the moment.

JH: How did you arrive at that way of working?

LG: I started off working at a restaurant because I was interested in food. The thing that I do now is more popular. I hear there are university courses that teach this kind of thing now, but back then, I didn’t know of anyone that was doing things in this way.

“You know what I hate more than anything? Moodboards. I think moodboards are killers of dreams and ideas” – Laila Gohar

JH: How did you realise you wanted to create sculptures from food?

LG: The food is never really the point. I care about food, but I don’t … It’s not so much about building a dish and layering the flavours; it’s more about what happens in the moment. I use food as an icebreaker and hijack it to disrupt a certain energy. That’s why my work tends to be a bit surreal and whimsical; people are not sure that it’s real.

JH: Is it healing because we lose touch with that sense of childlike wonder when we get older?

LG: Most of us lose that sense of wonder, imagination and play. We just become so practical and I hate practicality. It inhibits us in so many ways – as adults we’re constrained because we have to do things in a certain way, and that’s always really pissed me off. Why is it that as we grow up, our imagination becomes small?

JH: Let’s talk about your process. How do your ideas start and develop?

LG: I always have a bank of ideas in my head, things that come to me in different moments. You know what I hate more than anything? Moodboards. I think moodboards are killers of dreams and ideas. Instead of starting with an idea, you’re starting with 30 other people’s ideas! Sometimes clients ask for them, and my lovely agent has to talk them into the fact that I don’t do it.

My work is about setting the stage for people to be uninhibited, to feel more like children, to break the ice, to allow people this space to wonder, to question: is this real? Can I touch it? Can I not? If I touch it am I like breaking the rules? I notice that people become like children when interacting with my work; that’s really central to what I do.

JH: Does your background in Cairo play into your work?

LG: Like many young people, I rejected where I came from for a long time. I come from a culture that’s thousands of years old and so rich but it’s taken me some years to gain the perspective to be able to appreciate it. The history is so ancient and rich and there are these inventions and ways of doing things that I find inspiring now. Although I don’t make Egyptian or Middle Eastern food, I’m definitely inspired by the hospitality of southern Mediterranean and Middle Eastern people.

JH: When you describe your childhood, it sounds like you wanted to get away, but your work is also very social – it’s all about hospitality.

LG: I definitely wasn’t a loner or a sad kid. I liked to be around people, but there was a part of me that felt alone in the midst of all of that. Growing up in Cairo, hospitality is a huge part of the culture. I once came across something that said that the origins of Middle Eastern hospitality relate to nomadic travellers who moved around and had to find shelter and food. People would take them in and that’s part of the reason hospitality is so integral to life there. It’s this mentality of ‘the more the merrier’. [My childhood] was very social and non-exclusive. Anyone could bring whoever they wanted, it was an open-door policy.

JH: Did you ever think, I’ll balance 12 olives on top of each other and see what happens?

LG: My mum was very concerned with table manners. I would always mess around with things and she would be like, ‘Don’t play with your food’. A lot of parents say that to their kids, but it’s kind of ironic that all these years later I’ve made a living from that.

“My mum was very concerned with table manners. I would always mess around with things and she would be like, ‘Don’t play with your food’. It’s kind of ironic that all these years later I’ve made a living from that” – Laila Gohar

JH: How do dreams influence your creativity?

LG: I did psychoanalysis for three or four years, and it was very regimented. I would go to the office three times a week. It’s a big time commitment, but I was really interested in the process and in the dream world. For a while, I had lucid dreaming, but it was pretty bad. I always felt like I was being buried alive and couldn’t wake myself.

I sometimes dream of things that I want to do for work. When that happens I get really excited and I immediately write them down because they’re often good ideas, unlike the ones I have when I’m awake. Sometimes your dreams don’t really make sense, there’s not necessarily a plot line, but those are really interesting for psychoanalysis because they lead to different trails.

JH: What’s the next event you’re planning at the moment?

LG: God, I have so many things right now that I do with different brands. But I’m really excited as I’ve carved out Fridays where I don’t do any of my regular studio work – my employees don’t come in – and I go into my studio by myself and do things just for the sake of doing them. There’s no time, goal, or client, and I just tinker around with different things. It’s so nice to have time to play.

An Invitation To Dream, curated by Jefferson Hack for Moncler, is on show at Milan Central Station until April 21.